I've written about retirement and the history of retirement here more than once.

This is one of those threads that was started off in draft a long time ago, several months actually, and then never finished. At the time it was started, I'd been present when a person employed in my field, but not yet of Social Security age, made a comment in frustration over something about retiring, and another lawyer present dismissed it out of hand, even though that lawyer is even closer to that age, with a "oh no, now let's not talk that way". It surprised me.

Since that time, I've encountered a bunch of additional talk about retirement in various circles, which may be because I'm in my middle, middle, 50s, and maybe that's when you start to hear about that. For that matter, to my huge surprise, some lawyers I personally know, whom I've always thought were about my age (maybe they're slightly older) are in fact retiring.

I have no close personal experience with retirement.

My father didn't live long enough to retire. He was 62 years old at the time of his death, having made it I suppose to minimal retirement age, but he was hanging on with the intent to make it to 65. That's always the advice all the retirement folks give you, based on what are some faulty assumptions, not the least being that you'll live to age 65 or appreciably beyond it. He was pretty clearly ready and wanting to retire, however, and was talking a bit about it.

Indeed, he'd been talking about it for at least a few years prior back into my final university years. By that time I think he was pretty clearly burned out from working, which he'd done since he was very young, and was slowing down physically. Indeed, the scary thing there is that in some ways our two lives follow the same pattern in some things, which very much diverting in others. In terms of ways they parallel, he'd been working from a very young age, which I've also done, as he was employed at least part time since his mid teens, and I have been as well (my early teens actually). While he never ever complained about it, he also had lived a pretty hard life as his father had died when my father was just out of high school and that put my father into the full adult world with all its responsibilities very early. For me, my mother had been ill for years and years, which took quite a toll in other ways and while not as dramatic as the story for my father, it had a similar impact. That is, compared to some others, but only in some ways, I sort of went from my early teens to my quasi adult years and skipped over the teenage ones, sort of.

Given all that, he was getting worn out. While still in school I suggested to him that he ought to retire, even though he was still in his late 50s at the time, just a little older than I am now. I told him at least once, and perhaps more than once, that he didn't need to worry about me, and I could take care of myself. He should take care of himself, and go ahead and retire. He didn't.

Of course, it's easy when you are in your 20s to imagine that people in their 50s can retire, which isn't really the case. Probably a part of that was a sense of responsibility, which was highly developed in my father, that he couldn't retire as I was in school, which is something I worried about at the time. But then my mother's illness was likely also a major factor. He no doubt felt he had to make it to full retirement age given all the factors he was faced with. He did not.*

His father didn't either, dying in his 40s.

And his father's father did not as well, although he died in his 80s. He was multiply employed during his life, being a part owners in a store and also a post master. At some point he became a city judge, accordingly achieving a judicial career aspiration of mine that I'm not going to achieve. In fact, he recessed a case early for the noon break as he wasn't feeling well and then went home and died.

Of course, that's only part of the story of my ancestors and that's unfair, as your maternal great grandparents are just as much a part of your story as your paternal ones. The point is, I don't have any recollections, like some people do of "when my grandfather retired" or "when my father retired". Both of my grandfathers were dead before I was born and neither of them lived into their 60s (my mother's father was 58 when died). My father didn't live long enough to retire either.

So perhaps that means I don't appreciate the nature of retirement and why a person wouldn't retire.

Or perhaps I appreciate it more.

I'm not old enough to retire myself, now being two years junior to the age of death of my maternal grandfather, but I'm old enough to hear the conversations about it and listen to them. Indeed, that's true of anyone making into their 40s.

In my case, however, I'd started hearing about them in my 20s, as I was a National Guardsmen. Retirement is a draw of being a Guardsman, or at least it was then, in the oilfield depression of the 1980s. Lots of men, and we were mostly all men in those days when combat, and we were combat arms, was the role of men, were unemployed or underemployed at that time and the Guard provided desperately needed cash, just like deer and antelope season put meat on the table. As a lot of those men were Vietnam veterans and had at least two, if not more, years of military service in prior to joining the Guard, and they'd been in the Guard for awhile, reserve retirement was something that was really on their minds even if they had to wait age 60 to draw it, which most of them were not anywhere near being able to do. Hard times made retirement pretty real to them. It was only vaguely real to me, as I was in college and had a long ways to go before any such thing could be the case for me.

Well that's no longer true, which makes my presence as a silent third party in topics about retirement a different sort of thing than it was earlier. And I have some distinct views.

One thing that really surprises me quite frankly is the degree to which people accept the common advice about keeping working once you can retire, or even have a stated desire to never really do so. I'm not telling anyone to retire and as I'm not at retirement age as it is, or Social Security retirement age, any opinion I have on that sort of things is not really fully informed. But one thing that's really struck me in regard to it is how many people simply assume that they're going to retire and then be perfectly okay for enjoying life while not working or, alternatively, that they'll be fine to keep on at occupations that were physically or mentally taxing for people in their 20s, 30s, and 40s, when they're in their much older years.

Many things won't work that way.

Indeed, for most, at least to a degree, they don't.

People who track human happiness, or perhaps just the happiness of Americans in general, sometimes note that the elderly are the happiest demographic, which is not only true, but frankly sad. By and large their daily struggles are over, and by and large, given the glass and steel and cubicle world that we've made, and the abandonment of structures that gave life meaning, most people frankly aren't very happy during their long working years. That in and of itself has to make a person wonder why all the advice exists not to retire. Statistics year after year paint a very grim view of American working culture in psychological terms. Telling people to suck it up and keep on keeping on may not be the best advice.

It might also not be because once a person hits 50, and frankly for men it's 40, things become dicier health wise all the time. People are generally in fairly good health in their 20s and 30s, but things begin to catch up with them soon thereafter. If you are in any group of men in their 40s you'll be shocked to see some who look twenty years older than that and others who look twenty years younger. Injuries, genetics and daily living catch up with people.

As just such an example, this past week (this was written on September 23), the state bar circulated the news that a lawyer in Cheyenne had died, and in looking it up, I saw that she had died of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 50. Not old. This can be caused by a lot of different conditions, including an injury. But it can also be caused by high blood pressure and other things that you genetic makeup may predispose you to. In that case, generally if its detected early enough, you'll make it into a longer life. An aunt of mine who had high blood pressure, for example, made it into her 90s, whereas my grandfather, who also did, didn't make it so long and passed away in his 40s, as earlier noted. The key there is that it was detected in his case at an age that they couldn't really do anything about, although frankly he was heavy and that no doubt didn't help things at all.

Anyhow, that's just one such example. I'm in pretty good shape in my mid 50s but I'll note that a friend of mine who is the same age about walked me into the ground during sage chicken season. Keep in mind on that we both walked for miles, so it's not like I made it a few yards and stopped. But the point here is that he's in really good shape, and that's in part due to his work, which keeps him that way.

In contrast, a couple of colleagues I vaguely know are at the point where they're a physical mess. There's a variety of reasons for that but if I were to hear that they were physically incapacitated or died, it wouldn't surprise me at all. Lifestyle, in those cases, is clearly an element.

All of this deals with people in their 50s, not their 60s. The 50s are the decade where you really start to pay the piper for the dance. By the 60s the bill is really coming due in spades.

And this doesn't really take into account things you just can't do much about but which hit some people anyhow. Women who had no warning will develop breast cancer irrespective of their never having smoked and the like. Men will start developing prostate cancer simply because they're men. Other rarer forms of various diseases hit people without warning and without known cause. And all of that just deals with physical ailments.

For some the more dreaded diseases, the ones of the mind, really start to come in during their 50s or even their 40s. That's fairly rare however. But by the late 60s that's less and less true. Not everyone gets them by any means, but when Americans talk of retirement and the "I'm going to work until my 70s" talk comes out, its as if nobody ever is so afflicted.

Indeed, not do those ailments rob many people of their old ages, but directly and in terms of vicarious impact (being married to somebody in mental decline is no treat), it's a problem that's so significant that it ought to be addressed in terms of not "when will you retire" but "you must retire".

Ronald Reagan was 70 years old when elected President, which was seriously regarded as quite old for the office at the time. Since that time the United States has come to entertain increasingly older and older Presidents. Reagan, according to those who knew him well or who have studied him, was an extremely intelligent man who affected a lesser intellect in the same way that Dwight Eisenhower had earlier in his career. Nonetheless there's some fairly serious speculation on whether Reagan's dementia had manifested its onset during his second term.

The United States to date has been extraordinarily lucky that it has not yet had a President or a Supreme Court Justice who clearly suffers from dementia. We will sooner or later if we continue to believe that simply occupying those offices makes a person exempt from being afflicted. The Supreme Court is particularly remarkable in this regard in that the occupants of that court are often ancient. The recent health problems of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg give a really good example of how, sooner or later, there's going to be a real disaster on the bench. In her case, her afflictions were physical and not mental, but any rational person has to concede that, absent a change in how the court is staffed, sooner or later some justice is going to be afflicted with dementia and its not going to be caught until its fairly severe. Even at that, it's almost certain that the Justice's staff will work to conceal it until its simply not capable of being concealed.

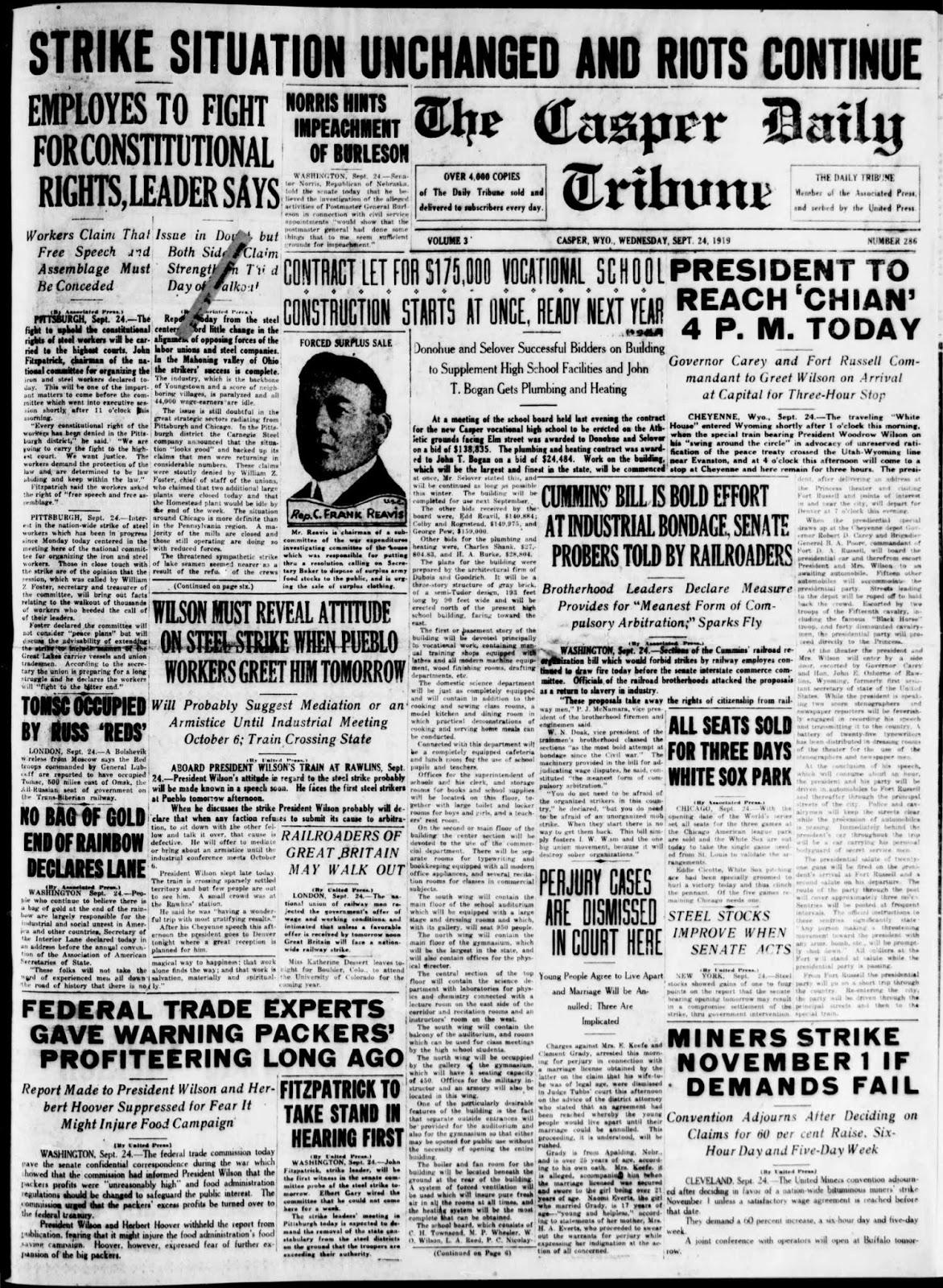

Woodrow Wilson exhibited a slender body form that's the more or less modern metro ideal, but his health was horrific. Suffering from high blood pressure, Wilson had suffered his first stroke in 1896 and would have subsequent episodes prior to his debilitating stroke of 1919. Wilson was 63 years of age at the time of his last stroke and had suffered his first when he was 40 years old.

This is a good argument for retirement to occur in certain occupations, particularly public occupations, prior to the potential ravages of time taking effect, although it isn't the only reason to have a mandatory retirement age in some occupations. Just taking that on in and of itself, however, a good argument can be made that in certain occupations, an out date should probably be mandated as to avoid the "Apres Moi, la deluge" type mentality that some acquire after long service.

Charles de Gaulle who couldn't conceive of a French republic without himself being there. A vigorous man his entire life, he departed life suddenly at age 79, just two years after leaving office. He predicted the "deluge" following his retirement, but it didn't come.

That's basically what we see at the Supreme Court level right now, and its surprisingly common with people in all walks of life. People come to the view that at some point they're completely indispensable. However, very few people really are. In odd circumstances, and perhaps in a small handful of jobs, the opposite is true. But it's exceedingly rare.

Mentally vigorous, but physically frail, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is now occupying one of the most powerful positions in the United States at 86 years of age, twenty years after the conventional retirement age. She's occupied the seat since she was 60 years old.

Indeed, examples to the contrary abound. And not only do they abound, a person who self occupies that indispensable position can in fact hurt the very institution that the imagine themselves critical to. Let's call it the Eamon De Valera Effect.

Eamon De Valera, who was the Irish Prime Minister from 1937 to 1959, and then President of Ireland from 1959 to 1973. He died two years after leaving office at age 92, having left office at 90 years of age.

De Valera was a force in Irish politics before there was a modern Ireland. Self appointing himself the Irish "President", recalling the term for the American head of state, during the Anglo Irish War, he went on to be an unyielding voice for Irish Republicanism and a central figure in the creation of the Irish Republic. He was the country's Prime Minister for twenty-two years before stepping up, so to speak, to the role of head of state which he occupied until he was 90 years old. He was a giant of Irish politics.

He also wasn't a George Washington of Irish politics who saw the need to step down and his own views came to so dominate Ireland that much of the country's current flirtation with flippancy may be put at his doorstep, or tombstone if you prefer. An extreme conservative in many ways, he created an agrarian state with a special relationship to the Church that the Church itself attempted to prevent but yielding to in the end. His view that he was indispensable to the Ireland he created may in fact have been somewhat correct, but that has proven to be a problem. By dominating Irish politics for so long, Ireland was not allowed to really evolve into a more modern state earlier on, which it would have done in a way which likely would have accommodated its culture and religion more fully. De Valera's refusal to go helped freeze Ireland in place for decades with the predictable result that when change inevitably came it came in a radicalized and ignorant fashion. De Valera would have done his country a huge favor if he'd retired upon reaching that age.

And that's the real risk those who imagine themselves to be so important run. Nobody lives forever, and by insisting that you control until nature determines you will not doesn't prevent a changing of the guard, it delays it, and delays it in a fashion which precludes it being done well. The United States Supreme Court has become the absolute poster institution for that fact. With no mandatory retirement age, Justices now serve into their extremely advanced age, well beyond the era of their appointments, and either attempt to time their retirement such that they will be replaced with somebody they more or less approve of, or they simply determine to occupy the position until they die.

The entire process accordingly subjects the entire country to constant turmoil at the Supreme Court level, a turmoil that's gotten worse as the country has become increasingly politically divided. It's also caused the dead hand of prior Presidents to be remarkably present many years after their original appointments. The recent retirement of Justice Kennedy gives a good example of that. Kennedy was appointed by Ronald Reagan and, in spite of not having been the conservative justice that was hoped for, it seems that he cast back towards the politics of his appointer in scheduling his retirement. In contrasts, Clinton appointee Ginsberg seems to be holding on until somebody more like Clinton is in office, assuming that she simply doesn't choose to depart when called to the final docket.

And that's the real risk those who imagine themselves to be so important run. Nobody lives forever, and by insisting that you control until nature determines you will not doesn't prevent a changing of the guard, it delays it, and delays it in a fashion which precludes it being done well. The United States Supreme Court has become the absolute poster institution for that fact. With no mandatory retirement age, Justices now serve into their extremely advanced age, well beyond the era of their appointments, and either attempt to time their retirement such that they will be replaced with somebody they more or less approve of, or they simply determine to occupy the position until they die.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, a disappointment to conservatives, seems to have reached back towards the President who appointed him in terms of choosing to retire when he did.

The entire process accordingly subjects the entire country to constant turmoil at the Supreme Court level, a turmoil that's gotten worse as the country has become increasingly politically divided. It's also caused the dead hand of prior Presidents to be remarkably present many years after their original appointments. The recent retirement of Justice Kennedy gives a good example of that. Kennedy was appointed by Ronald Reagan and, in spite of not having been the conservative justice that was hoped for, it seems that he cast back towards the politics of his appointer in scheduling his retirement. In contrasts, Clinton appointee Ginsberg seems to be holding on until somebody more like Clinton is in office, assuming that she simply doesn't choose to depart when called to the final docket.

That all pertains to important public offices, of course, so a person can logically argue that doesn't have much to do with conventional employment. And they'd be at least partially right. But there is something to it. An individual in a private institution can become as ossified as one in a public one, and the ravages of time are every bit as present.

As an example of that, years ago I was working on a contractual matter in which it was clear that something odd was going on with the other lawyer. When we gathered for the closing, it was clear that he'd become completely senile. His longtime secretary was doing the real work, Edith Wilson fashion, and doing it fairly well. But it wasn't quite right, and the explanation for that became clear at that point.

As an example of that, years ago I was working on a contractual matter in which it was clear that something odd was going on with the other lawyer. When we gathered for the closing, it was clear that he'd become completely senile. His longtime secretary was doing the real work, Edith Wilson fashion, and doing it fairly well. But it wasn't quite right, and the explanation for that became clear at that point.

Edith Wilson, President Wilson's second wife (his first predeceased him). She effectively operated as President while Woodrow Wilson was debilitated due to a stoke. Fortunately for the country, she did a good job at it.

That is an extreme example,, but many others abound. Finding examples of institutions in which an elderly figure holds on when he shouldn't are fairly easy to find. Family businesses of all types, in which a founder brings his children into them and then won't yield to their decisions, are particularly common, often leading to the end of the business when a frustrated child simply chooses to quit.

Outside of that, i.e., debilitation and limitation coming into play for those not retiring when they can, there's also a certain sadness necessarily associated with the "I'll keep working" point of view that's hard to escape.

We all as children have very broad interests. That continues through our teen years and early 20s, but the impact of work and the "occupational identify" tends to operate to destroy it or bury it in a lot of people. People who when young had a wide variety of interests drop one, then another, then another, until by the time they are within a decade or so of retirement they've stripped all their interest down to work. If you run into the friends of your youth and ask them about some activity they did when younger the reply "oh. . . I haven't done that for years" is a common one. Indeed, if they have an outside interest its often one that's frighteningly associated with their occupations, either as an auxiliary way of doing business, an activity directly associated with it, or worse of all, an activity that was designed to drown it out at all costs. Young men who had been outdoorsmen in their youth are found, forty years later, maybe golfing, watching over mock juries, or drinking. Not a good development. For quite a few, work is all that's left.

Not all, of course. Not by other means. But one thing about retiring is that it gives a person a chance to do those things, perhaps, again.

It also gives a person the chance to exercise what may have been a secondary vocation, or even their primary one. Their "calling", so to speak.

Just recently here I wrote about Norman Maclean, the author of A River Runs Through It. I have a second post in the hopper regarding Maclean that I may, or may not, finish, dealing with the fact that his published writings all come late in life. Indeed, they came after he had retired as an English professor. My thought was that, to a degree, that was a tragedy, particularly as he left a selection of long worked upon but unfinished work.

But what that doesn't completely acknowledge it is that writing is really hard work. At least good writing is. People who write are working at writing and its taxing. People who write at history, moreover, or historical fiction, are not only writers, their researchers.

This has become increasingly obvious to me as I'm not only a lawyer, I'm a writer. I write here constantly, of course, in part because I'm a compulsive writer, but in part because writing a lot hones your skills at writing. And not all writing is the same, although the more you write for a wider audience the more all of your writing begins to be of that type.

Anyhow, as a writer who is employed full time, indeed who has two jobs, I'm like Maclean. I'm not getting my writing completed. I may well have to wait until I retire, assuming I live that long. But that's the point. Maclean likely didn't finish his works written while he as a professor because he was working. They had to wait. People who have that auxiliary vocation, or even primary one, that are suppressed due to the need to work take that vocation with them to the grave if they never retire or retire too late to exercise it.

And there are a lot of those sorts of things. For example, in my state there is or was a Catholic Priest who didn't take up that vocation, which he had all along, until he was retired. In that time period he'd been married, raised a family, and become a widower. At that point, he sought leave to enter the seminary and take up a calling he'd heard in his youth but never heeded. Indeed, remarkably, both he and one of his children were priests at the same time. A well known local lawyer did something similar to that when he retired from the law and became a rabbi.

Some time ago I read of an instance in which a Canadian man whose father had been a career Canadian Army officer entered the Canadian Army in his 40s. The Canadian Army still allows for that and he'd always wanted to be a soldier, but life had interrupted his goal. He finally acted on it, after leaving his civilian employment. Locally a retired investment broker works enthusiastically at a fishing tackle store as fishing was always his real passion. A bull testing I was at a while back had an ancient man who was assisting as a lab tech for the veterinarian, who turned out to be his son. It was his chance to be outdoors around animals.

I can't say, except in the case of public servants, that anyone "must" retire. Ultimately, that's an individual choice. But I really question where societal pressure operates against it. "Work a few more years" presumes you have those years when you might not. "I don't ever want to retire" suggests that maybe you've forgotten your other joys or are afraid to have to face life without the roar of work. Time moves on and we don't get it back. For some, working until the grave or until quite close the grave may be their real joy. But for most it won't be and pondering something else, if they can, should be done.

*And then I took over in that department, although my mother had revived a bit in my father's very last years.