It's a scary thought for a lot of folks.

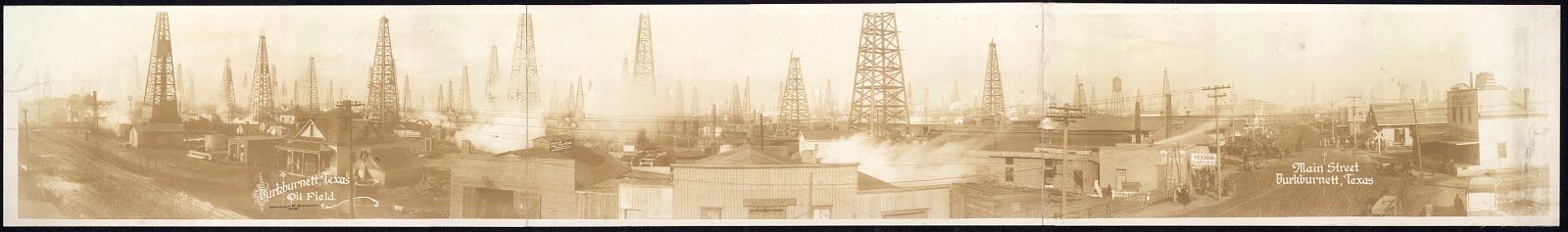

Burkburnett Texas, February 17, 1919. Clearly a boom was on when this photograph was taken.

To include the folks who budget things for the state, although they certainly aren't the only ones.

Indeed, it would mean a lot in regard to my daily bread myself. In a major, major way at that.

And for a lot of Wyomingites simply in terms of how they put food on the table.

Indeed, it would mean a lot in regard to my daily bread myself. In a major, major way at that.

And for a lot of Wyomingites simply in terms of how they put food on the table.

Let alone budget for darned near everything, in every manner.

It's a topic that I hesitate to even put up, as simply mentioning it provokes such strong reactions in some quarters that you get accused of sympathizing with the Reds.

It's a topic that I hesitate to even put up, as simply mentioning it provokes such strong reactions in some quarters that you get accused of sympathizing with the Reds.

Is there a new red sheriff in town? Well, maybe. This is a 1989 poster of the Polish political party Solidarity, a political party that leaned on Catholic social teaching and which toppled,in surprisingly rapid fashion, the Polish Communist Party. Ironically, the poster borrowed an iconic American theme, the lone sheriff striding into town and imposing order alone against everyone's collective wishes. Solidarity was borrowing a powerful American symbol in this, but this might indeed be the symbol of what's happening here in the real West right now. The sheriff isn't a Red, and warning about what's occurring, or may be, doesn't make him cowardly. It makes him careful.

Note what I'm not doing. I'm not urging anything here. I'm pondering if we should ponder. And the resulting of that pondering is I think we better start to.

On my unfinished posts here that linger and linger is one Titled "Before the Oil", and by unfinished, I mean all I have is a caption. I started it on January 31, 2015 and haven't gotten around to finishing it, IE., writing it. That post is about Alaska and it dates back to my having recently, at that time, been on vacation. The last vacation I was on. Which was apparently in 2014.

I don't take much time off.

Anyhow, that post would have been an interesting one and will be as Alaska doesn't have a long oil history even if has a major role in oil today. So it's easy to analyze the before and after, unlike Wyoming, which has a very long history with oil in particular, as well as coal. Our association with coal and oil is so long that imagining something like that is nearly unimaginable.

Indeed, coal's is longer, but was really more concentrated. When the Union Pacific started crossing the nation, and hence the state, its engineers looked for coal and where it located it, it started arranging for it to be mined for obvious reasons. For that reason, there's an early string of now abandoned coal mines along the Union Pacific route through Wyoming. I don't know that the UP chose to run lines close to coal, but it sure worked out that way, and for the ultimate benefit of the railroad. Wyoming had, as amazing as it is to think of it now, some significant underground mines at that time and it even retained one as late as the 1980s when I was a geology student specializing in coal at the University of Wyoming.

Library of Congress photograph of the dramatic statute in Rock Springs called "Clearing the Haulway", a monument to miners. I've photographed it as well, but can't find my photo, darn it. Rock Springs, it should be noted, is on the Union Pacific rail line. The town is a UP town, but it was also very much a mining town with local populations drawn in part from regions of Europe in which mining was the means of making a living.

But petroleum always fascinated the state and, particularly in Central Wyoming, it was always seen as the great economic hope to come. Natrona County's newspapers started reporting about hopeful oil prospects as early as the 1890s, an era in which the use of petroleum oil was much more limited, but certainly not nonexistent, than it would become. If that seems early, a Cheyenne newspaper was reporting on oil making the residents of the state rich as early as 1867.

1867.

Cheyenne newspaper from 1867 with the headline "Oil!"

That's early.

Casper newspaper with an article about petroleum from 1889. Wyoming wasn't yet a state and Casper was in Carbon County, which must have been a gigantic sized county at the time.

Casper Wyoming had its first refinery operating by 1894. That refinery didn't last long, but a more substantial one came around early in the first decade of the 20th Century in the form of the Franco American Oil Refinery, which was a foreign owned entity. Their refinery was located just outside of town at a location that's now well within it.

Franco American Oil Refinery

The Midwest Refining company bought it and replaced it with another refinery located near the North Platte, which in turn was bought by Standard Oil. That refinery plugged along as a fairly substantial entity until a giant revolution in petroleum prospects accelerated the world, the nation and Wyoming into the Oil Age, with that event being World War One.

Midwest Oil Refinery, Casper Wyoming. 1912.

World War One caused a revolution in oil consumption and production in a way that, looking back, we could have predicted, but which at the time couldn't have been. Automobiles had been around since the late 19th Century, to be sure, but going into the war the inroads vehicles were making were steady, but not absolutely dominant. Most urban dwellers still got to work, and simply around, on foot or by foot and trolley. Most rural individuals still relied heavily on horses. Cars were a factor, and had been, but not an overwhelming presence.

Railroad oil tank cars being filled at the Standard Oil Refinery in 1920. Oil tank cars look nearly identical to this today.

On the rails, everything, almost, was coal fired. And on the seas many things remained coal fired as well, although the British Navy had started the revolution in petroleum prior to the Great War, as already discussed here, by starting to switch to petroleum fired boilers. In 1912 it decided that its capitol ships would all be built that way. The American Navy followed suit soon thereafter. The Great War would see coal fired ships still in use, but navies were trying to convert to petroleum as fast as they could and were using vast quantities of it. In Wyoming, a Naval Petroleum Oil Reserve was created to have a stock of petroleum oil for future conflicts.

Grass Creek, Park County Wyoming, 1916.

After the war, everything began to accelerate in an unpredictably and unbelievably fast fashion, with a slight break for a post war economic depression. After people crawled out of that, and started to recover from the deprivation of the war and started to spend.

The U.S. entered a recession, bizarrely, while World War One was still on, with that lasting from August 1918 until March 1919. I'm not sure what actually caused the onset of the recession, but the end of the war certainly accelerated it, but the country briefly pulled out of it only to fall into a depression in January 1920 which lasted until 1922. I'm not an expert on these economic ups and downs, but they're rarely looked at very carefully as the following Roaring Twenties and subsequent Great Depression drown them out. Indeed, the Great Depression, which lasted until the onset of World War Two, remained such a strong memory in people's minds that it was widely expected that the economy would collapse back into it following the Second World War, which of course did not occur.

The reason it didn't occur is that people had a pent up set of spending desires that dated back to the early 1930s and, following the war, they engaged in it. People who had held off spending for better than a decade just weren't willing to wait.

Something like that followed World War One as well, except the impact of it was delayed and frankly not really well understood. The U.S. had endured an entire series of post Civil War recessions and depressions that are almost forgotten now prior to World War One. Indeed, the country had basically been in a recession from 1910 until 1914, when World War One brought an end to it. Technically two recessions, the 1910-11 recession is regarded as "mild" but featured deflation, something that only actually occurs in depressions as a rule. The Federal Reserve Act was passed during the second recession to address what was going on in it, but also to address a series of negative economic fluctuations dating back to 1907.

Now in fairness, some of these fluctuations were short and not severe, but the recession of 1920-22 was sufficiently severe that its regarded by some as a depression, which would make it one of three such events in American history. If put all together, what we see is that the economy was in trouble from at least least 1913 and then the World War One economy brought an end to it, but starting in 1917 the United States was in a huge war which featured full employment but which also saw a real lack of goods on American shelves. The end of the war and the resulting cancellation of government contracts combined with the rapid discharge of servicemen threw the country into a new recession which started to amazingly rebound in March 1919, but a severe reversal occurred in 1920.

By the time the nation pulled out of the recession the country had endured about a decade of pretty significant ups and downs. In that same period, however, new and old things had entered the market or had been improved. For example, radios arrived and commercial broadcasts started in 1920.

Movies were coming out weekly, and had been for some time, but they were becoming more and more popular.

Felix the Cat, a popular cartoon series, debuted in November 1919.

Rapid mail by airplane became a regular thing.

Glamorous and dangerous, air mail pilots.

And automobiles were no longer a novelty but rather were in high demand.

1919 Dodge Brothers advertisement. Farmers were slow to adopt automobiles for a variety of reasons.

The Lincoln Highway across the United States, in somewhat theoretical existence since 1913, was put to the test by the U.S. Army symbolizing the arrival of the automobiles. Ostensibly an act to test new Army vehicles for their ruggedness and to also test the ability of the United States to use highways rather than and in addition to rail for mobilization, the Army crossed the continent travelling from Washington D. C. to Oakland California on the Lincoln Highway.

U.S. Army vehicles in Nebraska on their way to California from Washington D. C. in 1919.

It'd be done again in 1920. By that point the direction of these efforts were clear.

States, for their part, began to pave their sections of the highway.

Money was flowing and part of that money was now being, additionally, spent illegally because of Prohibition and a wild abandonment of all sorts of mores that had been widely accepted just a few years earlier. From 1922 to 1929 massive spending, including stock market spending, and massive social change, roared through the country. But a lot of that roaring was being done in cars.

Advertisement for the 1929 Ford Model A Cabriolet convertible. The Model A is a legend, but it was only actually made from 1927 to 1931. Selling in the millions, it replaced the much more primitive Model T which was produced from 1908 to 1927.

This is not intended to be a history of the automobile, and indeed, we have to be careful about suggesting that the automobile reached modern status in the 1920s. It didn't. All over the country farms, ranches and numerous urban delivery entities continued to use horses. The horse wasn't replaced overnight., exactly.

But prediction of the replacement of the horse had been going on back into the 1890s, with both automobiles and bicycles being equine rivals at first. Far sighted individuals had been predicting the horses dominance to be doomed back that far. At the same time, as the need for horses actually began to decline, their specialization by breed and type ironically increased. Farmers who had previously preferred generic draft horses began and who had sold their surplus in towns now began to pick breeds that they knew would sell. And at the same time, legislation hostile to automobiles, prior to the 1920s, appeared. By the 1920s, that was all ending in one way or another. Draft horses kept on in towns and in agricultural use, but automobiles had clearly arrived and were expanding into widespread use, including widespread female use, something that was a real novelty. The Petroleum age had arrived.

Looked at this way, Wyoming's entire post contact history can be divided into Economic Eras. Many people who are fond of history really dislike it if you emphasize this too much, but the fact of the matters is that all of North America's post contact history has been economically driven to a very large extent. If we do this, what we tend to find is that the history of the state divided up into 1) the fur market era, which ran from some time in the 1700s up until some murky date the 1850s when the Oregon Trail, which was already being used by immigrants since 1836, gave us 2) the military era, in which the dominant economic force was the U.S. Army, sent west to guard the frontier immigrant trains, which yielded to 3) the agricultural era, when cattle came into the state, ranching started to dominate and farming entered in earnest, which then yielded to 4) the oil and coal era, which came in around 1914 and which is still with us.

Something to note regarding all of these eras is that it is not the case, as some historians like to suggest, that when one economic force ceases to be the dominant one it ceases as a factor entirely. This is far from true in general and in Wyoming's case its definitely true. None of the prior economic forces have ever disappeared. Some may have radically altered over time, such as the "fur" era, which has changed to perhaps the outdoors industry over a long period of time, but nothing has really gone away. This is important for our analysis below.

Anyhow, a feature of economics eras is that there are distinct signs when one era is yielding to another, and that ought to really cause Wyomingites some concern at this point. Common features of economic eras that are closing out are:

- The technology of the new era becomes viable and starts to rapidly spread.

- The technology of the old era becomes suddenly much more diverse as it seeks to retain its position.

- Interests aligned with the new oncoming era at first seek public support to remain viable, but cease to do that once they are.

- Interests aligned with the old economic era do the reverse and start to seek public protection from the new competing forces as their economic advantage decreases.

And, and we should keep this in mind;

- Those whose livelihoods have been vested in the old economic era resist accepting that it can be possible that those interest s are about to fade.

Something else to keep in mind, and this is particularly important, is this;

- Changes in economic eras are slow and subtle as they come on, but once they reach the tipping point the change is exceedingly rapid.

Before we look at the first factors, lets consider the last one, because if we are in such an era, if history is our guide, things will change much more readily than we can imagine. Changes that are often thought of as requiring decades to occur can and do occur in less than a decade. That means that the second stand alone factor here about those with livelihoods vested in the old economic era, and like most Wyomingites I'm one of them, are usually taken brutally off guard when the change happens.

Let's take a misunderstood historical example as an illustration, one we've already mentioned, the change from equine transport to automotive transport. And lets compare them to the new ones, considering the factors set out above.

- The technology of the new era becomes viable and starts to rapidly spread.

People like to post images of cars and trucks form the teens and twenties in sort of a quaint fashion, recalling, in their minds, a simpler past. But that change wasn't quaint at all when it occurred. It was exciting and liberating for many, but it was an economic disaster for others.

Going through the factors we've listed above, automobiles were around since the 1890s and the Model T was introduced in 1908. The Model T was designed to be an affordable car and it in fact took off rapidly in the market. It didn't dominate transportation overnight, however, but there was a point at which it became obvious how things were going. Production numbers for the car look like this, taking into account all models:

|

1920 463,451 |

1921 971,610 |

1922 1,301,067 |

1923 2,011,125 |

1924 1,922,048 |

1925 1,911,706 |

1926 1,554,465 |

1927 399,725 |

That's quite telling. 10,660 was a lot of cars for a car in 1909. But 498,342, the year after World War One, is something else entirely (and note how producing itself greatly increased during the war years). Over 2,000,000 in 1923, the year after the post war depression, is something else yet again. In comparison, Tesla, the hallmark electric car. . . right now, produced just over 245,000 vehicles last year.

But something else occurred in here that is significant. When Ford started off with the Model T all other automobiles were really expensive. By 1920, however, it no longer had that market corned. Dodge Brothers was competing directly with the Ford Motor Company. Chrysler would be founded in 1925. General Motors had been founded in 1908 but like Dodge, it was also competing directly with Ford by the 1920s. And there were a zillion other manufacturers that were competing for the American market.

Ford had made the personal auto viable in 1908. It took less than ten years for that to become obvious. That's not a long time.

Tesla has been trying to make the electric car viable since 2003. Tesla's are too expensive for most people.

But now every major manufacturer is planning an electric car. Audi, during the Super Bowl, debuted an advertisement with a lot of underlying subtle themes which introduces their new electric car. They intend 1/3d of their total production to be electric by 2025. It'll happen quicker than that, and Tesla is doomed. The new Audi electric car is effectively what the Model T was, in my view. Every car manufacturer will follow.

And not just car manufacturers, motorcycle manufacturers too. Harley Davidson, the maker of the iconic v twin motorcycle is working on an electric motorcycle. That surely shows which way the wind is blowing. And electric aircraft have arrived, with plans for commercial electrics on the drawing board. Norway plans to require aircraft to be electric in the foreseeable future.

Hmmm. . .

- The technology of the old era becomes suddenly much more diverse as it seeks to retain its position.

This may seem counter-intuitive, in no small part because when a new technology comes about its also diverse. But its' more diverse in the experimental stage, whereas the old technology is more diverse (again) in its passing stage.

By way of an example of the former, when automobiles first came about there were numerous competing engine systems. Some were electric early on. Steam cars were also around. Most cars soon came to run on gasoline, but some were diesels. Only diesels and gasoline engines automobiles survived up until just recently, when various electric cars started to be experimented with.

But now we see much the opposite occurring. In recent years there have been "hybrids", which essentially used the combustion engine as an electric generator part of the time. Engines have been redesigned to be computerized to boost their efficiency. Diesels have strongly entered the U.S. market, even as they're being banned in the European one. Electric cars are starting to see a set of common features however.

By way of another example, consider once again the horse.

People like to imagine that prior to the age of the automobile not only were horses in common use, which is of course, true, but that numerous breeds of horses were common and in use. In truth, that's not fully accurate.

There have always been various horse breeds, many of which are still with us, but some of which have departed the scene. But for most of American history, anyhow, while numerous horse breeds existed, they existed in the riding horse category, and even at that, most horses were grade. The military, which purchased vast numbers of horses for example, only concerned itself with type of horse, i.e., riding or draft, and not with breed, even though in the civilian world there were those who were very much concerned with riding breeds.

As automobiles came in, however, the military became much more concerned with breed and it entered the horse breeding world itself after World War One out of that concern and out of the concern that as automobiles came in a supply of good riding horses would evaporate. This basically resulted in the modern Quarter Horse breed, even though the breed itself certainly predates that, as the Army Remount program had a serious influence on Western horse breeding which before that had produced grade horses as a rule. And farmers, who had preferred a type of smaller draft horse called a "chunk" prior to the early 20th Century, began to use large draft breeds not because they favored them, they did not, but because the heavy transportation market in the cities, which remained heavy into horses well after automobiles entered the picture, became a major market and they preferred heavy drafts. Farmers had always depended on their being a surplus market for draft horses and they didn't feel the need to specialize prior to that. As the horse market waned, they not only felt the need but had to adapt to it by breeding a horse which was in fact not ideal for their own use.

We seem to be seeing a bit of that again.

- Interests aligned with the new oncoming era at first seek public support to remain viable, but cease to do that once they are.

While its often forgotten later on, new technologies tend to lean on public support to get rolling. Once they're viable, that tends to drop off.

The railroads are a good example of this. Railroads started popping up in the United States before the Civil War but the obvious problem they had was securing rights of way and the expense of building long distance rail lines. As long as most of the lines were short this could be taken care of by a combination of favoring them with the power of eminent domain, a type of public support, and private financing.

But the real revolution in rail transportation in the U.S. is when the coasts were linked by rail. Once that was done, rail transportation, which was already big on the East coast, entered an entirely new phase. And that was done with massive public support.

No rail line wanted to enter into the market on its own, nor could any afford to. Even the Transcontinental line that was built was the product of two companies formed for that purpose, not one. The incentive for the companies to engaged in the construction, however, was the massive amount of land given to them by the United States in order to do it.

That seems to often be overlooked in the story of American economic history. Americans tend to believe that they're a radically free market nation, but the best evidence is that this isn't always so. The U.S. gave the railroads thousands upon thousands of acres in the West in order to make their effort to build a transcontinental railroad viable. In addition, the U.S., in 1872, passed the Mining Law of 1872 that made it possible to enter on to the public lands for mineral exploration without paying for the land. Indeed, it could be mined while belonging to the US or the miners could later patent it and acquire ownership. Later the U.S. provided for a leasing system for coal and oil exploration.

The point of this is that while we tend not to notice it much, much of the early Coal age which became the Oil age was started off with a species of public support. That public support remained and still remains in the form of some of the laws mentioned as well as with the state and local funding of highways. The U.S. and the various states didn't have to take on the task of building and maintaining highways, which is a type of subsidy to automotive transportation, but they have.

Leaping forward the U.S. again under took to incentivize wind generation of electricity as well as solar generation of the same with tax incentives. The goal of this was to make those industries viable, which admittedly would ultimately cut into coal fired electricity generation. Early on this was widely criticized as supporting industries that weren't viable, but now they are. While support still exists and is still debated, it's become clear that both wind and solar no longer need that to take on coal in competition, and coal is clearly fading as both wind and solar rise.

That's significant to our story as this story deals with both coal and oil. We've written a lot here about the plight of coal, and less about that in regard to oil, but both are connected here. A criticism of electric transportation, which it should be noted could expand to almost all rail at some point as well as automobiles, si that it really isn't hydrocarbon free. And indeed, in a place like Wyoming, like a lot of other places, that's true. If the electricity comes from a coal fired power plant the vehicle still uses fossil fuels whether the owner of the car feels green or not. If it comes from wind or solar, however, the story is different.

Tunnel on the Tans-Siberian Railroad. The Russian transcontinental rail line is electric.

- Interests aligned with the old economic era do the reverse and start to seek public protection from the new competing forces as their economic advantage decreases.

The opposite is also true. As an old economic force starts to loose out in competition with a new one, legislation pops up supporting the old one and trying to keep it running. When this occurs, quite frankly, it's a really bad sign for the old industry.

This happened in regards to the onset of the automobile. Early on, once cars started to become common, legislation all over the United States was passed that was designed to hinder the use of the automobile in favor of the horse. A lot of this reads as really quaint and silly now, but it was serious at the time. People feared automobiles and worried about them startling horses and the like, but an element of resentment was also there.

Taking us forward to the present time, int the current legislature there's a bill that wold require companies retiring coal fire power plants to attempt to sell them before they close them.

Now, power companies are just that, companies, and they're in their line of enterprise in order to make money for the company. Now, in the modern American context I think all significant power companies are corporations or cooperatives (early on, a lot were run by municipalities, which is another example of how when technologies are young, they often get state assistance), which means that they are trying to make money for their shareholders or members, so that does add another element. It is possible that those shareholders may, for various reasons, desire their companies to head in a new direction, not all of which are economic reasons. After all, that's essentially what occurred to companies that did business in South Africa, their shareholders revolted on a wide scale. But by and large its unlikely that shareholders or members of power companies are going to mandate that they go "green", so to speak, although its not impossible.

Assuming that isn't the motivation for most power companies that shut a plant down, if they could sell it, they would. So that legislation may very well do nothing at all. But the thought that such legislation is necessary is a potential indicator that a real shift is in the wind.

- Those whose livelihoods have been vested in the old economic era resist accepting that it can be possible that those interest s are about to fade.

This was the next factor, or observation.

There's an entire famous American movie that's on this topic, and it was made at a time when the shift from equine transportation was still fairly fresh in mind. That film, The Magnificent Ambersons, contains a startling dinner conversation which starts off as an observation what automobiles will do ("extend roads to the county line". . . damage "the old business district") which develops into an argument between the young heir to an equine based fortune and goes on to become an erudite observation on automobiles and their existential impact. For those who haven't seen the 1942 Orson Welles classic, it's worth seeing.

By way of a real life example, a famous saddle maker of the period who had been in business for a long time and how benefited enormously from Army contracts was warning his fellows that automobiles were going to change everything. He turned out to be correct, and in fact unable to adjust himself. He committed suicide

The basic nature of things is that just because we have an occupation, or even an avocation, that depends on things staying the way they are does not mean that they will, that forces beyond everyone's control wont' change them, or that others don't want to change them. Only human forces that are contrary to nature, and many human movements of all kinds are, are doomed to failure, because they are contrary to nature. But technologies do not remain in place simply because people depend on them for their livelihoods.

This works a series of interesting impacts on debate as many people will argue that something "can't be" because its personally detrimental to them. But technologies in the abstract aren't inevitable in their use, nor are they normally good or evil, even though people often argue as if they are.

I note all of this as for Wyomingites it tend to be nearly impossible to really imagine the decline of the petroleum industry in particular. But then only recently it was nearly impossible to believe that the coal industry would decline. The decline in the latter was then argued to be merely a temporary matter.

This doesn't mean that contrary arguments to observed trends are ipso facto invalid. Far from it. But ones based on emotion alone don't carry much weight. Humans are extremely poor at predicting the future and and merely because there's a current trend in any one direction does not mean that it will necessarily carry forward.

- Changes in economic eras are slow and subtle as they come on, but once they reach the tipping point the change is exceedingly rapid.

We've dealt with this above, but this final point gets to why perhaps we should start pondering this now.

The very first automobile was introduce in 1769, but it was really just a weird novelty. The first internal combustion engined automobile was made in 1808, but the same is really true of it. The first really practical, in any sense, gasoline engined automobile was introduced in 1870, which is surprisingly early.

Early Benz automobile

That 1870 date is significant however, in that Karl Benz, in 1885, came out with the first production automobile. That was just fifteen years after Marcus introduced his semi viable 1870 car. Henry Ford founded the Ford Motor Company in 1903, just twenty two years later, and started making Model Ts in 1908. Model Ts went into mass production in 1913 and by the end of World War One, the direction of the future was pretty plain.

Looked at that way, a person could argue that well, look how long it took. But that doesn't provide much comfort.

Elwell Parker electric car, circa 1885.

Efforts to make really fuel efficient vehicles have been around for as long as the automobile, but in t he US it has been a focus ever since the 1973 Arab Oil Embargo. Efforts to make electric cars date back all the way to the very first vehicles, but like steam engined vehicles, they lost out in the competition, for technological reasons, to internal combustion engine vehicle, but that wasn't until the post World War One era.

Electric cars came back into production, although hardly noticed, in the 1950s, and mostly in Europe for limited use. They received attention in the United States, however, when a viable special purpose electric car was developed for NASA for moon exploration in the 1970s. While that was a highly specialized vehicle, the fact that it existed at all and that it worked couldn't help but draw attention to electric vehicles in an era when gasoline was becoming expensive.

Lunar Rover

In 2003, with increasing concerns about the use of fossil fuels developing in many places, Tesla Motors was founded, named after the highly eccentric electricity pioneer. Tesla has been working since that time to make their product really viable economically and it seem to have now achieved that, on a limited basis.

And now Audi. . . .

But in context, the time frame of this is remarkably similar to what occurred to equine transportation, including the early struggle by the competing technology to get its bearings. If that's correct, we likely just reached the tipping point and a real electrical propulsion revolution may be about to start.

Something similar may be going on with electrical generation, which in this case would actually be in concert with what we've noted for vehicles.

Replacing coal fired power plants with something else is clearly technologically possible and indeed other nations have done it or are doing it. Indeed, as early as the 50s through 70s there were serious arguments by the proponents of nuclear power to replace coal fired plants with nuclear ones, something that was only arrested by the illogical silly fear that exists over nuclear power. Even at that, however, rival power generation methods (other than hydroelectric which has always been there) existed.

Before we look at that, however, its interesting that one of the things that's really kept coal around, ironically, are "green" concerns. Nuclear power is incredibly clean in the generation phase, if not the rod disposal phase, and very easily could have completely replaced coal power plants by the late 1970s. If that had occurred, much of the current debate on these topics would not be occurring. But confusion of atomic weaponry with atomic power generation kept that occurring, a triumph of confused logic. Only in very major navies has a limited exception occurred in a hardly noticed fashion.

Likewise, green opposition to hydroelectric has meant that this also very clean means of generating power basically stopped being developed in the 1970s. While there certainly are detriments to dams, the benefits fairly obviously outweigh the disadvantages. Most American rivers capable of serious hydroelectric power generation were developed by the 1950s, but this isn't the case in regards to small local possibilities and the Canadian potential was never anywhere near fully developed as the American market, which is what it would have been developed for, opposed it.

Be that as it may, in the 1970s new rival technologies and old not fully developed ones. The new one was solar power.

Solar power was greatly explored during the 1970s, and at one time there were arguments that it should and would come to be on every house. As fuel prices declined in the 80s, however, so did solar. . . seemingly.

It actually didn't. What happened is that those developing the technology continued to work on it. By the 90s it was showing up on all kids of remote local applications and its extremely common in that use today. From there, however, it's started to be used in "farms", i.e., generation facilities. Now they're showing up all over and solar generation companies lease ground prospectively just like oil and gas companies do.

Solar and wind are now so viable that they can compete against coal on their own, so that technological and fiscal hurdle has been reached. Coal fired power plants, however, are on the decline, even though many claim that this just can't happen and isn't happening. Where they are really being built is overseas, but overseas in an economy that's partially a command economy and which is undergoing an economic downturn. An economy like that, given the need to keep a large population employed and satisfied, can switch gears and rebuild, if it has to, pretty quickly.

Now, none of this guaranties that these trends continue. But what it does suggests is this.

Assuming that the old Wyoming economy, by which we mean the Petroleum Age economy, must keep on keeping on is gambling a bit, or at least it appears to.

But do we have a plan for that? Well, we always claim that the plan is to "diversify the economy", but that's only a plan to try to level the peaks and valleys of the boom and bust economy we've had throughout the Petroleum Age. Really contemplating a big shift away from fossil fuels is something we've never really done.

Perhaps, even if it isn't to occur, we should, just in case it is. That wouldn't mean abandoning what is in favor of what might be, but planning carefully for what could occur, at least to some degree?

But what would that even mean?

Of course, maybe it doesn't matter, as maybe, at least with petroleum, the trend line isn't really there. As noted, humans are horrifically bad at predicting the future in any sense.

Solar and wind are now so viable that they can compete against coal on their own, so that technological and fiscal hurdle has been reached. Coal fired power plants, however, are on the decline, even though many claim that this just can't happen and isn't happening. Where they are really being built is overseas, but overseas in an economy that's partially a command economy and which is undergoing an economic downturn. An economy like that, given the need to keep a large population employed and satisfied, can switch gears and rebuild, if it has to, pretty quickly.

Now, none of this guaranties that these trends continue. But what it does suggests is this.

Assuming that the old Wyoming economy, by which we mean the Petroleum Age economy, must keep on keeping on is gambling a bit, or at least it appears to.

But do we have a plan for that? Well, we always claim that the plan is to "diversify the economy", but that's only a plan to try to level the peaks and valleys of the boom and bust economy we've had throughout the Petroleum Age. Really contemplating a big shift away from fossil fuels is something we've never really done.

Perhaps, even if it isn't to occur, we should, just in case it is. That wouldn't mean abandoning what is in favor of what might be, but planning carefully for what could occur, at least to some degree?

But what would that even mean?

Of course, maybe it doesn't matter, as maybe, at least with petroleum, the trend line isn't really there. As noted, humans are horrifically bad at predicting the future in any sense.