Cary Grant and Myrna Loy from Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House.

People think I am exaggerating when I say 50% of people's problems, strife and anger would go away if they just started dressing well, but I'm not.

Dressing in a way that makes you feel good about yourself will make you feel better about others and the world too.

This is both a revived thread, and a new one. It's one of many topics that shows up here in one way or another, including in stored drafts that I start off on, and then fail to finish.

This one started: I wrote my first entry here and put it up for posting to be run yesterday.

Then I read this on Twitter:

Atticus Finch (of Georgia)

I had an attorney I had never met show up at my office to take a deposition one day in blue jeans - blue jeans! I was insulted and lost respect for that attorney.

How we dress does matter. It is a form of manners.

I agree with that comment in that how we dress, matters.

But it does show the regional nature of things, but still we should consider this carefully.

I've posted on this before, but I used to wear dark black Levi's or Lees to court on occasion, combined with a sports coat and a tie. When I did that, I'd wear cowboy boots as well. Wearing cowboy boots to court is isn't unusual here. I've seen it done a lot.

In retrospect, I haven't seen the jeans, such as I noted, with sports coat and tie all that often, but I have seen it. I very rarely do that anymore, however. Part of the reason I do not, however, is that I don't travel nearly as much as I used to, thanks to COVID 19 and its impact on travel and the law. Travel was routine, COVID came in, and hard behind COVID were Zoom and Teams.

Indeed, I've appeared in a few Teams hearing recently in which the Judge was in the same town as me. Prior to Teams and Zoom, we had a few telephonic hearings we'd do, but if we were in town, we were expected to show up.

Not anymore.

Anyhow, I've seen a lawyer wear blue jeans in court exactly once. That particular lawyer was a working stockman and was appearing in the court in the county in which he lived. Nobody said anything. He was otherwise in jacket and tie. I have seen lawyers in blue jeans in depositions plenty of times, however. Most of the time prior to COVID it was in combination with jacket and tie, but even in the couple of years before COVID this was changing.

I still wear a tie.

I had some lawyers from Texas show up a while back and they were in jeans and new cowboy boots. There's working cowboy boots (all of mine are of that type), "ropers", which aren't cowboy boots, dress boots that locals wear, and then the weird dress boots that locals don't wear, but Texans do.

I don't get that kind.

Anyhow, in order to wear cowboy boots as dress shoes, you have to know how to wear cowboy boots. Some people affect a high water appearance with their dress shoes, and frankly do so on purpose. Men's trousers are supposed to "break" over the shoes. I.e., you aren't supposed to see the socks. But for some odd reason, some Ivy League educated people wear their trousers "high water" so you can always see their socks.

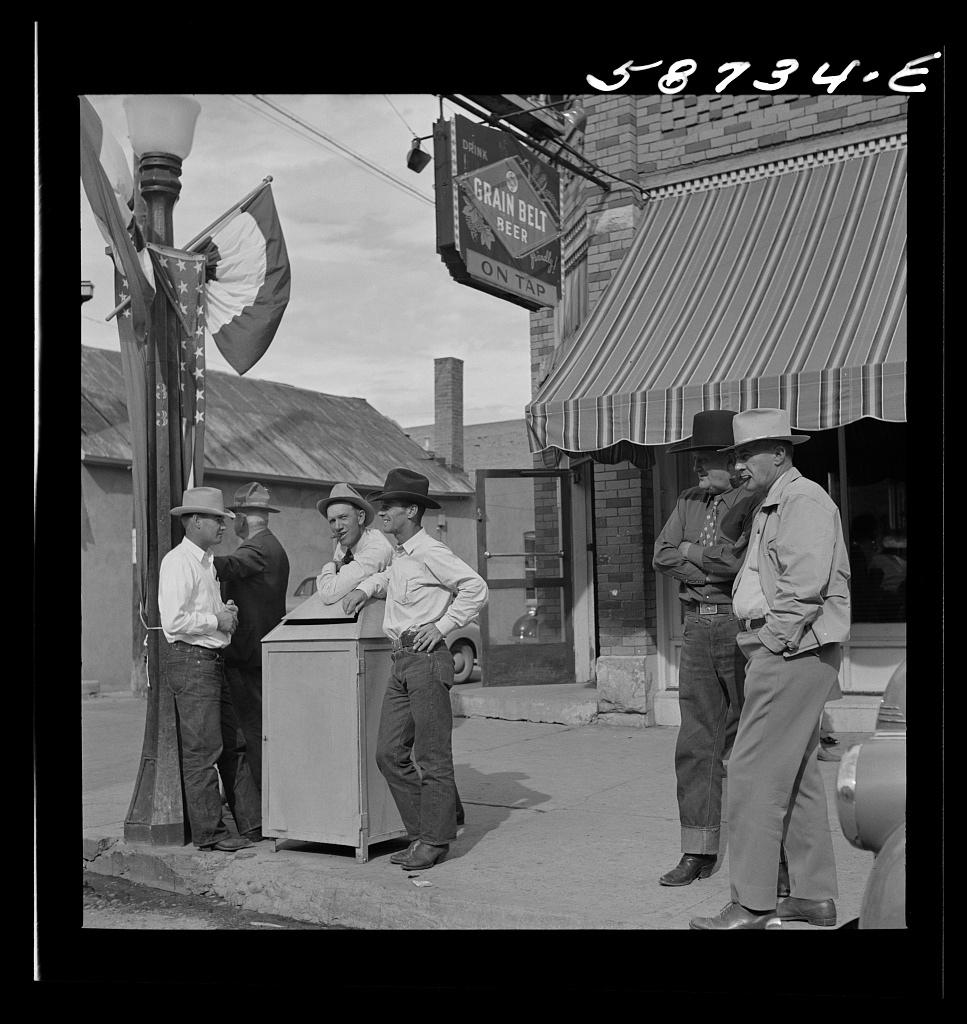

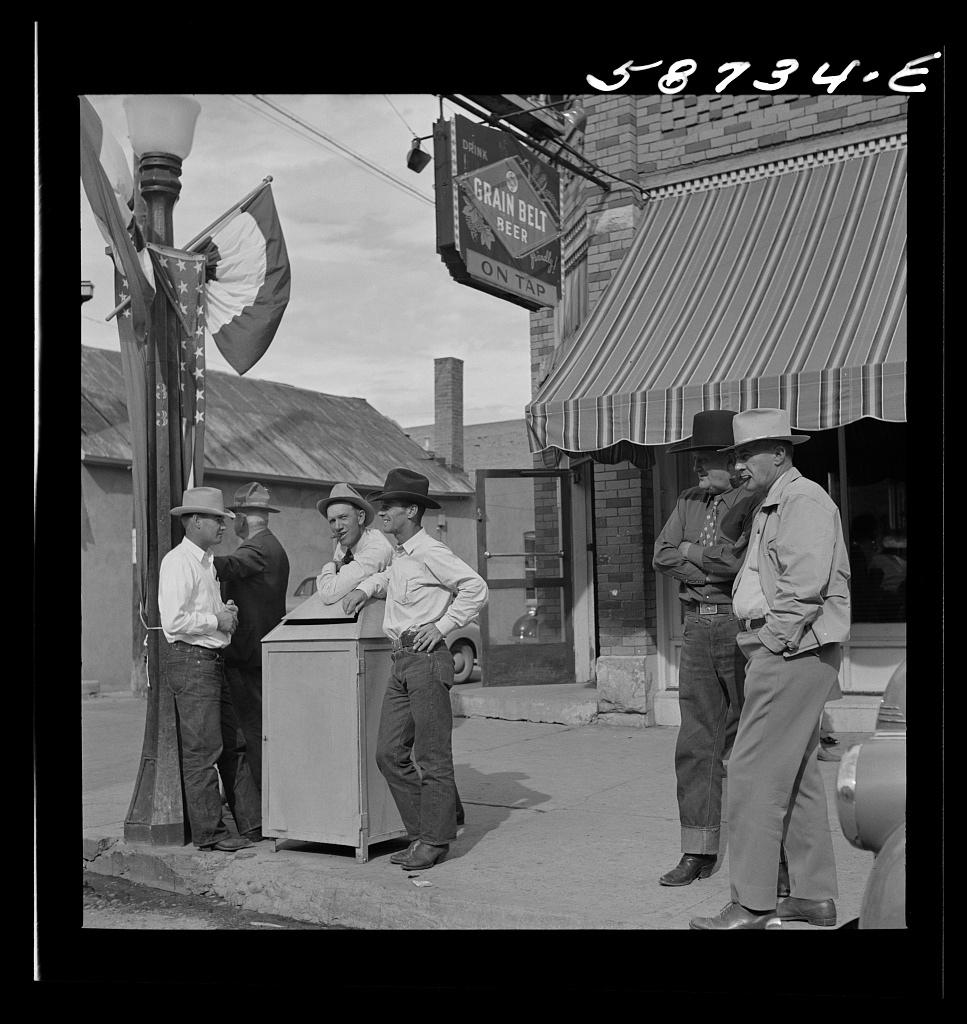

Stockmen, Sheridan Wyoming, 1944. This is an interesting photograph and it must have been taken as something was going on in the town where the photo was taken, Sheridan Wyoming. The clean white shirts are a pretty typical semi formal dress for ranchers. All the hats are good (clean). Only he older rancher with the beat up Montana Peak hat is wearing a suit. The stockman on the left is wearing baggy jeans that drape over his heels, still a very common way to wear them amongst working stockmen. All of the visible heels are "doggin' heels" which are common only amongst working stockmen.

Cowboy boots, properly worn, are never ever worn high water.

Anyhow, it's interesting to note, note that Atticus does, that years ago I went to a Federal Trial in Cheyenne in which I was making a very limited appearance. After the day I had dinner with the defendant, who had been a Supreme Court Justice in Montana (where they are elected). The main lawyer in the matter wore a suit every day, but he wore dress cowboy boots with them. The retired S.Ct justice, when that lawyer got up to do something, turned to me with real anger and noted, as I was wearing a suit with wingtips, that "I'm glad to see somebody dresses like a lawyer around here".

Given that at that time I often wore cowboy boots at work and even at court it was quite ironic.

The last time I wore cowboy boots in a trial was over a decade ago, I'm sure.* It was a relatively long trial and I'd basically cycled through my dress clothes so I wore a sports coat, black Levi's and my cowboy boots. Nobody said anything, but later the plaintiff's lawyer grieved the judge over something in another case and claimed, referring to this one, that he had favored me as he hadn't said anything about it while he had, she claimed, about her shoes. I don't recall anything ever being said about her shoes.

That was the last time. I didn't want to be seen to be inappropriate in any fashion, again.

That does bring up suits, however.

My legal assistant dresses professionally every day. I really should. I do a lot, as there are things I go to constantly in which I appear as a lawyer, and I feel that I should dress as a lawyer is expected to, when I do, which involves at least wearing a button down shirt (usually white) and a tie

I do the same for depositions, but I"m almost the only one anymore. I'll go to a deposition and everyone is dressed down in blue jeans and the like. People actually comment as I'm not dressed in that fashion.

Indeed, I went to the eye doctor's the other day and was dressed for work, which on that occasion was khaki trousers, button down shirt, and a tie. The person who checked me in joked that "I was too fancy to be there".

Times have really changed. I recall a time when you went to the doctor's office and the doctors where wearing ties, or alternatively a smock that buttoned to the neck.

Physicians in the 1940s

Dentist into the 1980s, which I know due to my household, wore a dress shirt and sports coat to work, then a dental smock at work. My father preferred clip on ties, probably has he had to change back and forth.

When I was growing up, I didn't know how to tie a tie.

Probably a lot of kids in my generational cohort didn't. I didn't wear ties growing up. I never went to a school that had uniforms, and the dress code, to the extent there was one, seems to have largely pertained to junior high, where (boys) were not allowed to wear t-shirs advertising beer, and girls were not allowed to wear halter tops. I can recall a boy being sent to the office once for wearing a beer t-shirt, although he'd worn it before, and a girl being sent for wearing a halter top that was quite a bit too less, so to speak.

Junior high and high school here were like the Wild West when I attended and by high school the authorities had simply given up on dress codes, I think. We were largely self policing however, as by that time self appearance standards start to awkwardly kick in. Kid from ranches dressed lake cowboys of the era and they were the real deal. Otherwise we wore typical clothing of the era, which often involved t-shirts, which is odd to look back on now as I'm always cold and I never just wear a t-shirt anymore (I've had people comment on that). Girls had generally become quite self conscious and therefore wore nicer clothes than boys as a rule, although the code, to the extent there was one, had clearly been suspended to the extent that I recall being confronted in a crowded hall by an amply endowed girl I did not know who had chosen to come to school in a very thing t-shirt and no brassier, which would have gotten a person sent home in any other era.** It was shocking enough that I recall it even now, over 40 years later.

Events, I'd note, largely didn't require a tie. I.e., school events. We didn't dress up for nearly anything. More significant social events, however were different, such as weddings or funerals, which is tough if you don't actually own any dress clothes and you've never had to wear them, particularly in the 1970s. The 70s were a black hole for dress clothes with awful suits and loud or pastel colors. I recall my father and I having to go out to get some dress trousers for me for a wedding and ending up with pastel light blue polyester dress pants, a true horror. I hated them then, and I still do.

Anyhow, a self declared position of mine in my late teens was that I was never going to have a job in which I had to wear a tie every day. It was arrogant and naive, but it did express my career goals quite well. I thought at the time I'd work outdoors in one of the sciences.

Be that as it may, soon after high school I attended basic training, and learned how to tie a tie there. The Army still issues ties. I still tie a tie the way I learned at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma.

Even as a geology student I started to learn how to dress more formally, and thankfully the horrific polyester era was over. For the most part I dressed every day as geologist in the field do. I wore L. L. Bean chamois shirts in the winter and t-shirts in the summer. By that time, however, I was gravitating strongly back to the rural dress patter, reinforced by basic training, where we the original patter heavy BDU shirt every day, unless it was the surface temperature of the sun, at which point we could go down to t-shirts. Cowboys, you'll note, almost always ear long sleeve shirts and frankly anymore, I do too. Just recently, in fact, somebody asked me "do you ever wear a t-shirt". I truthfully answered, "yes, underneath a long sleeve shirt".

My parents taught me well, but it took some time for me to learn.

In law school our professors dressed professionally every day. Men wore jacket and tie every day, and one professor, our business law professor, wore a suit every day., Oddly, it didn't make an impression on me at the time, but it sunk enough, I guess, that by the time I was getting ready to graduate I knew how to dress like a lawyer. By the summer before I graduated I owned two Brooks Brothers suits, one bought for a wedding, and two Brooks Brothers ties. I still have one of the ties.

I don't have either suit. Suits, I've found cause an odd waist line expansion on me such that all I have to do in order to gain weight is buy a suit. In fairness, at the time I bought the first two I was incredibly, probably dangerously, think. There's a long story behind that, but I'm not naturally really thin. My father and grandfather were stout. Not fat, but stout. My mother was think, and seemingly everyone in her entire family is. I seem to fit in somewhere in between, but having been a bit stout when I was in junior high and the first two years of high school (and then having rocketed to thin), I've always been a bit conscious of it and I do tend to watch my weight. I'm as heavy now as I've ever been, but I'm still not approaching stout.

When I was first practicing law, the rules of dressing were made plain to me on day one. In the winter we wore shirt and tie every day. In the summer, we could wear polo shirts in the office. Court rules had at one time provided that during the summer lawyers could wear short sleeved dress shirts and ties, and dispense with jackets, and the "Summer Rules" were still cited, even though they were no longer published as they had been. I've never owned a short sleeved dress shirt and I've never appeared in court without a jacket. About fifteen years after that a new district court judge imposed new rules, which included no khaki trousers in court.

Still, even before COVID, things were really changing. You'd see lawyers wearing ties in their offices less and less. Levi's began to appear. And COVID just put things in the basement. Lawyers will now appear in Zoom meetings with the Court without jacket and tie (not me). I had one senior Court lawyer hold a meeting in which he didn't have one. It's been odd.

And I dress way down in the office if I don't have to meet anyone.

I presently have two suits, only one of which I really like. I wish I had a double breasted suit like two Brooks Brothers suits I've owned in the past. They seem really hard to get now. The good one I have is a heavy wool suit. I have a grey wool suit that's just too thin. I need to have, really, at least two more suits but I haven't had a long trial since COVID and I keep thinking, at age 61, that I only have a few more years of practice and I don't want to invest in work clothing that will likely outlast me.

The other one now has some very tiny holes, which would likely indicate some moths got to it at some time. It's hard to notice, but there there. It's embarrassing.

So I need to get some new suits, I guess.

And not just that

Ties I've had from the first years of my practice have really lasted, but I'm starting to throw them out as worn. I can't really ignore that any longer. And having waited to long, the bill for suiting back up is going to be monstrous, and at age 62, sort of a bad, if necessary, investment. I'll have to practice until I"m 80, or start wearing ties to Mass or something, to make that pay off.

Footnotes

*I've never had a pair of "dress cowboy boots", like many people do. I've had cowboy boots for a long time, of course, but never a fancy pair. Every pair I've ever owned was a working pair, even if they were reserved for office and town wear at first.

My regular cowboy boots. The ones I wear to work, when I wear cowboy boots to work.

I wear cowboy boots in the office less than I used to for a couple of reasons. One is that I often wear a pair of "ropers" that were bought for my son. They're Ariats and really comfortable, and look Western. The other is that I have arthritis in my right foot from an accident years ago, and my old cowboy boots sometimes get uncomfortable, and sometimes they don't, at the office.

**

"Mr. Bernstein: A fellow will remember a lot of things you wouldn't think he'd remember. You take me. One day, back in 1896, I was crossing over to Jersey on the ferry, and as we pulled out, there was another ferry pulling in, and on it there was a girl waiting to get off. A white dress she had on. She was carrying a white parasol. I only saw her for one second. She didn't see me at all, but I'll bet a month hasn't gone by since that I haven't thought of that girl."

Citizen Kane.

I have found this observation from this movie to be really true. The fact that I can recall the incident clearly is something I find curious. That was the one and only time I ever encountered the girl noted, and I'm not pining for her, nor even proud of the recollection, but it's really clear. I stepped around a student and she was right there. She was short and Hispanic and looked up at me, but she was really showing, and probably conscious of it and embarrassed. I was too. It was only a very brief encounter, but for whatever reason, I can still recall it pretty readily, but I don't think about it every month.

Memory is interesting.