WE recently posted this item on our Some Gave All blog, the one that's dedicated to memorials. I'm repeating that post here, in its entirety, as it deals with something that's very much on point for this blog, but which we haven't addressed yet. And I'm adding significantly to it.

Some Gave All: Cheyenne Wyoming's Buffalo Soldier Monument, Verno...: These are photographs of a small park in Cheyenne Wyoming, just off of F. E. Warren Air Force Base, which was formerly Ft. F. E. Warren...

These are photographs of a small park in Cheyenne Wyoming, just off of F. E. Warren Air Force Base, which was formerly Ft. F. E. Warren, and originally Ft. D. A. Russell. the park memorializes various things significant to Cheyenne's military history, which has always been a significant aspect of Wyoming's capitol.

The most notable feature of the park is an African American cavalryman, a "Buffalo Soldier". Ft. D. A. Russell saw troops of the 9th Cavalry, one of the two all black cavalry regiments in the segregated Army, stationed at the post.

The monument includes a memorial to 1st Lt. Vernon J. Baker, a Cheyenne native, who won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions during World War Two.

This blog, of course, tracks history and changes, and here we see a truly huge one in terms of American society. A story of race relations that's well known to students of the U.S. Army and American history, but often off the map for those who have only occasional or passing familiarity with these topics.

For many years, at least since the 1950s, the Armed Forces have been a significant employer for American minorities with American blacks having had a particularly strong association with it. And yet, this is really a fairly recent story in some ways, while not in others. It's also one that appears to be changing.

When I went to basic training in 1982, one of my two Drill Instructors, SSgt Ronald E. Adams, was black. The Senior Drill Instructor for our Battery was black. Our Battery Commander, Cpt. Harris, was black. None of this seems the slightest bit remarkable. And yet this wouldn't have been the case in 1942, nor even probably in 1952. A significant change certainly occurred, and what that change was, was the desegregation of the Armed Forces. And by extension, the Armed Forces became a major factor in the change in American race relations, and a major factor in black employment.

It surprises many now to learn that the Armed Forces ever enforced a racial policy, but for over 150 years it did. And that policy was to put blacks, but not other minority races (normally) in separate military units in the case of the Army, or later, in the case of the Navy, in separate duty roles. Interestingly, this policy did not always exist so that itself reflects something about our society.

The Revolution to 1792

Blacks, the poor, and immigrants were so common in the Continental Army that a French commentor at Yorktown noted his amazement that an army of poorly equipped, disheveled, poor, blacks and immigrants could defeat the professional British army.

When the US first formed its military, during the Revolution, policies were interestingly mixed and remained so throughout the war. Depending upon what colony a person came from, blacks could be admitted to service or not, or even compelled to services in some instance. Slavery, of course, existed everywhere throughout the thirteen colonies that rebelled (it's often forgotten that there was a fourteenth, the Canadian one, that didn't), but it was already in the decline in the northern colonies which did not feature plantations as part of their agricultural economy. Slavery, even at that time, was particularly associated with, but certainly not limited to, plantations, a distinct type of production agriculture.

Early in the war some blacks volunteered and served with various colonial units that were raised or mustered for the war. And keep in mind that being a member of the militia was mandatory, not elective, for free men, or at least free white men. When Congress formed the Continental Army, however, its commander, George Washington, a Southern planter, did not want blacks in it and banned their enlistment at first. This reflected his origin, no doubt, as he also found the northern soldiers he commanded, at first, to be rather difficult to take culturally. However, he acclimated himself to northerners in various ways, including accepting that northern units had recruited and employed black soldiers. Some northern units in the Revolution had up to 1/5th of their ranks made up of black soldiers. One militia unit from Rhode Island was completely made up, in the enlisted ranks, of black soldiers. The Navy, a Continental force, took blacks into its ranks, unlike the Continental Army (at least outright), reflecting a bit of a different culture that existed in seafaring communities and also the need, right from the onset, to equip a force that competed with commercial fleets for manpower and which required special skills that were concentrated in maritime communities.

The British, taking advantage of the official prohibition on blacks enlisting in the Continental Army, openly declared that they would do it, which they did, and that service in the British Army would mean freedom after the war. This was in fact attractive to blacks, so much so that at the end of the war slaves from both Jefferson's and Washington's plantations were among the "property" that were returned to the victorious Americans (a quite raw deal, in my view, for those black British servicemen). In reaction, Congress reversed the official prohibition on the enlistment of black soldiers in the Continental Army and authorized the reenlistment of blacks who were already in it. Washington, it should be noted, ordered this to be done prior to Congress officially approving it, which says something about the evolution of his views, but also about the fear that blacks would see the British as their protectors, which clearly some did, and not without good reason. While this didn't authorize recruitment of free blacks, that fairly clearly did occur, and moreover, the owners of slaves were allowed to be provided as substitutes for their owners in militias in the north and the south, a fairly surprising policy if a person thinks about it carefully. These enlisted, black, slave, militiamen served in what were otherwise white militia units.

As noted, the policy was different for the Navy. The Navy enlisted black seamen and it had little choice but to do so. A fairly significant number of blacks served in the Navy during the Revolution. And while there are source that claim otherwise, the nature of sea duty at the time didn't really allow for segregation. Blacks surely wouldn't advance in sea service, but as yeomen sailors their lot and service was about the same as whites.

While the concept of Marines as a truly separate service didn't exist at the time of the Revolution, with Marines being sea borne infantry in the classic sense at that time, a few blacks are known to have served in the very small American Marine Corps that existed for the period of the Revolution (and which went briefly out of existence thereafter). There to, that reflected the realities of sea service.

The overall story of our early history in these regards is therefore quite interesting. Blacks were not at liberty for obvious reasons to join as freely as whites, and there was no way that they were going to become officers, but they did see some integrated service in the land armies of the United States, and further integrated service in the Navy. A fairly promising start, eh? Well, things would soon change.

1792 to 1862

Following the Revolution, in 1792, Congress acted to prohibit the enlistment of black soldiers into the Army, a policy which remained in place until 1862. Congress did not, however, prohibit the enlistment of blacks into the Navy. This has to reflect the retrenchment of views following relief from the threat of the British, who were threatening to free black slaves, and who were clearly headed that way in general in terms of the evolution of their views. Indeed, contrary to our common concept of the American Revolution standing purely for liberty, the British held much more egalitarian views towards Catholics, Indians and Blacks within their domain than the thirteen rebelling colonies did. Following the Revolution, only repression towards Catholics slackened a bit, but probably mostly because they constituted such a tiny minority of American colonist and also because it wasn't really practical to repress Catholics officially without repressing the various Protestant minority faiths as well, so legislative efforts to do that were abandoned.

The Navy was, quite frankly, the more significant service at the time, as the United States came out of the Revolution as a maritime power, not really a land power, and navies cannot be rapidly built, but must rather be maintained. The size of the Army shrank to tiny following the Revolution, a policy that the Unites States generally followed, basing its land defense on militias, until after World War Two, save for time of war itself. As the United States had to keep a Navy, and navies were recruited from men in maritime communities, and as commercial employment was better paying than Navy duty, omitting blacks from the Navy was impossible. But, and not to be too cynical, it also seems to have at least partially reflected the port culture that exists in all maritime communities which have always been very mixed in terms of populations and races. Indeed, the Navy is known to have had at least one black junior officer at the time of the war with the Barbary Pirates, which is truly an amazing thing, in the context of those times, to contemplate. A large number of enlisted sailors were black, with estimates ranging from 1/4 of the enlisted ranks early in the 19th Century to well over half of the enlisted ranks, although that later estimate strikes me as high. Suffice it to say, with so many sailors being black, blacks served in all enlisted rolls in the Navy, not in just segregated duties.

Interestingly, when the Marine Corps was reconstituted blacks were banned being enlisted in it, along with "mulattoes" and Indians. This was a policy much different from the remainder of the Navy's, of which the Marine Corps was very much part, but apparently it reflected a policy in the British Marines, upon which the United States Marine Corps was based, to have high social cohesion among Marines. One of the roles of Marines in those days was to put down mutinies aboard ship, and the thinking was that men who had to do that had to be bonded mostly to themselves, and not to anyone else, and therefore they should all have as much of the same background as possible. That resulted in Marines having an official all white policy starting in 1798.

While blacks were officially banned from Army service, a little occurred in the tiny Army, probably on a blind eye basis. In militias, Louisiana, which was exempted form the 1792 law by way of a treaty with France securing its acquisition, was an exception in chief as it had an all black militia unit, making it an interesting exception in that, of course, it was one of the states that would attempt to depart in the Civil War. This is really remarkable for a Southern state, in that in stark contrast to northern militias, southern ones often had suppression of a slave rebellion distinctly in mind in terms of their organization and purpose.

This was the basic situation that existed at the time of the War of 1812. The support of that war, however, would start to show a trend that would seemingly reflect itself in regards to this history for some time. Support for the war was stronger in the South, than the North, and the largely militia forces that were raised to fight in the war were heavily southern as the war moved on from its initial stages, while the Navy remained a maritime navy. Opinions over the war itself were sharply divided by region as the war dragged on, with New England becoming increasingly disenchanted with the war to the point of near resistance to it in some fashions.

The patterns developing during the War of 1812 continued on after the war that, by the Mexican War, they were pretty fixed. The Navy remained integrated at the enlisted level while the racial exclusion in the Army, if anything, increased as the officer corps of the Army came to be increasingly influenced by the South. The South, being much less economically developed than the North, sent a higher percentage of its sons into the Army. While this should have been counteracted to a certain degree by an officer corps that was largely provided by West Point, the better educational opportunities in the North tended to mean that Northern officers disproportionately entered the Corps of Engineers and also tended to to have greater outside economic opportunities, while Southern officers were more likely to remain in combat arms and stay in the service. During the Mexican War this expressed itself in the form of an officer corps that was heavily prejudiced against Catholic German and Irish immigrant soldiers. This resulted in a high rate of desertion and the only instance in American history of a unit of defectors serving in the opposing army.

The high desertion rate, combined with the formation of the Mexican artillery unit made up of American deserters, the San Patricio's, shook up the United States Army severely, and caused it to do what it later would be very adept at. It acted as an agent of social change well before the society it served did, and that would in some ways be significant in terms of the later development of this story. The Army entered the Mexican War a white, Anglo Saxon, American institution. But it soon worked its way to peace with its Catholic Irish and German soldiers. Not long after the Mexican War the Army would develop into a haven for them, and by the time of the Civil War, the officer corps was beginning to see the incorporation of them. The Civil War would also see the reintroduction of blacks into the Army.

The Civil War

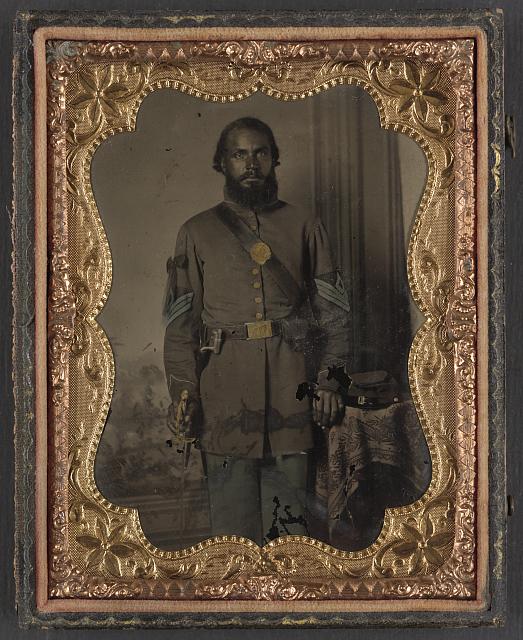

Black cavalry sergeant. This sergeant is dressed in the classic late war fashion, complete with high riding boots which only entered cavalry service late in the Civil War. Photographs like this demonstrate that, contrary to myth, black troops, while not paid at the same rate as white troops, were equipped equally as well as any other soldier.

That blacks would enter into the Army during the Civil War now seems so obvious as to be self evident, but they were not serving in any numbers in the Army prior to the war. Blacks were not allowed to enlist at first, in spite of a pronounced desire to do so, in part because there was a fear that their recruitment would push border states into the Confederacy. Congress, however, authorized their enlistment in 1862 and by the war's end over 180,000 blacks had served in the Union Army.

Black infantry First Sergeant, Civil War. The saber is likely a studio prop, which together with revolvers frequently appear in Civil War studio photographs where they'd otherwise be surprising. This infantry NCO's bayonet can be seen carried on his belt. He wears the full frock coat, which became less common as the war went on.

In spite of its long history of enlisting free blacks the Navy also had some trepidation of receiving escaped slaves into service, but it was soon doing so. Navy service continued to be more egalitarian, no doubt based on the long history of blacks in the Navy, and unlike the Army the Navy did not discriminate in terms of pay or privilege, although it did in promotion. By the wars end, some black sailors were serving as Petty Officers, a fairly significant enlisted rank in the Navy.

A black sailor of the U.S. Navy during the Civil War. This sailor appears to be very young, but very young sailors were common in navies throughout the world at the time.

Confident looking black sailor, Civil War. Note the pinky ring.

It is worthy to note, however, that the position of blacks, not surprisingly, fared poorer than that of Indians to some degree, depending upon the region of origin of the Indians at the time. Not all Indians were citizens by quite some measure at that time, but those who were saw no segregation in service and at least one rose to the rank of a general officer in the Army. Indians also saw service in the Confederate army, showing that the South was uniquely prejudicial in these regards.

1865 to 1914

Cavalryman of the 9th Cavalry.

Black troops had performed well and had proven themselves during the Civil War which caused Congress to authorize the retention of four black regiments, two infantry and two cavalry, in the post war Army. These became the 9th Cavalry, the 10th Cavalry, the 24th Infantry and the 25th Infantry. It is to these troops that the nickname

"Buffalo Soldier" attached, and it is a soldier in this service, one of the cavalrymen of the 9th or 10th Cavalry Regiments, which is depicted in the monument above. The term itself is lost to myth and the exact origin of it is unknown, although the modern assumption that it was associated with particular heroism is probably simply a myth.

Soldier of the 9th Cavalry.

This is not to say that the various black regiments did not give admirable frontier service. They did. Their performance was on par with the other regiments of the U.S. Army, although they were certainly unique and made up of men who had somewhat different motivations, although only somewhat, from the remainder of the Army. All in all, the enlisted ranks of the Frontier Army were made up of the economically disadvantaged, to say the least, with the other regular regiments heavily populated by Irish and German immigrants.

White officers of the 9th Cavalry.

The frontier period, and the period immediately following it, was the highwater market of black units in the U.S. Army. Serving in a segregated society, and in a segregated Army, the units were white officered but otherwise had exclusively black ranks. Their service was the same as for white units and they served very well, proving themselves as able combat units in the Indian campaigns of the West. A few, very few, blacks were commissioned as officers, with only one graduating from West Point, but until the 20th Century their lives were impossibly difficult and the service simply did not accept the presence of black officers, even though it did black enlisted men, even if within the same unit.

Lt. Henry O. Flipper, 10th U.S. Cavalry. A United States Military Academy graduate, Flipper's career was cut short by a charge of conduct unbecoming an officer which resulted in his discharge. His sentence was reduced in the 20th Century, but long after his 1940 death. In essence, his status as a black man doomed his military career, but he went on to a successful civilian career.

By the end of the Frontier era, black soldiers had proven themselves and their status was firmly established within the U.S. Army. In some ways, that Army saw its final hurrah in the Spanish American War, which was of course a conflict with a European power and not a Frontier campaign, but which was fought by troops and officers who were closing out the Frontier era. Black troops saw regular use in the war along side of the regular white regiments, just as they had continually since 1862.

Black cavalryman, probably in the 1870s or 1880s.

Starting very slowly, in 1887, the Army began to open up to black officers with John Hanks Alexander being the second black officer to graduate from West Point. Alexander was commissioned into the cavalry and unlike earlier black students at the United States Military Academy he received very little poor treatment while there. Alexander was soon joined by Charles Young, who received more resistance but, as Alexander died unexpectedly at age 30, the forceful Young was to be the much more influential figure.

Lt. Col. Charles Young. Young was an exceptional individual and was

the third black to graduate from the United States Military Academy and

the first black officer to reach the rank of Lt. Col. and the first to

command white troops in combat. He was retired for medical reasons at

the start of World War One in an act which is often regarded as one that

based on prejudice, but he did in fact die of a stroke while

subsequently serving as the military attache to the American embassy in

Liberia.

Young, like Alexander, entered the cavalry in a segregated regiment, but he was to later become notable for what turned out to be the curious last fully accepted deployment of black troops, that being their use in the Punitive Expedition. By that time Young was a Lt. Colonel in the 10th Cavalry, the first black soldier to achieve such a high rank in the U.S. Army, and he was the first black officer to command white troops in combat, which he did in an instance in Mexico when he was the senior officer when white and black troops were present.

Troopers of the 10th Cavalry who were taken captive in the June 1916 Battle of Caarrizal in Mexico. The battle was one that did not go well for U.S. forces and resulted in the capture of these men, something which has caused me to sometimes wonder, but without any written support, if this resulted in the sidelining of U.S. black combat troops during the Great War, to some extent.

The Navy, in contrast, started to go surprisingly backwards in this same time period. Having been the service which allowed blacks to serve on an unsegregated basis for all of its history, in the enlisted ranks, in 1893 it prohibited black enlistment except into the messmans corps, and thereafter black sailors served in the mess with a growing number of Filipinos. What caused this big change in direction is not clear to me, although it would seem to be evidence of a growing degree of prejudice in society in general, perhaps. Or perhaps more accurately, it may have reflected the big change in Navy demographics that came on with the end of the age of sail. Up through the Civil War the Navy had been a sailing ship Navy with crews that were drawn almost exclusively from maritime communities, which included blacks. Only shortly thereafter, however, the Navy became recognizable as the modern steel ship Navy, complete with battleships and entire classes of fast steel ships. The crews of these ships no longer really resembled the sold crews of seamen so much as they did technicians and the Navy populated the ships with crews drawn from across the country, and indeed very often young men entering the Navy came from the interior of the country, not from the ports. As this occurred, the prejudices of the interior seem to have entered the Navy, and blacks, who had served in all roles, no longer did after 1893.

Soldiers of the 24th Infantry in the Philippines, 1902. Fighting in the Philippines would carry on until just prior to World War One.

World War One

At the start of World War One, it would have been logical to suppose that the four black regiments in the U.S. Army would be joined by additional black volunteer units, and indeed they were, but there was significant resistance towards this being done, and black units received some resistance. Not one of the U.S. Army's regular black combat units saw service in the war. The 10th Cavalry and the 24th Infantry spent the war on the border with Mexico, where they did see combat with Mexican forces, but they never deployed to Europe. Of course, in the case of cavalry, cavalry remained an important element of our forces along the border, which was very active, throughout the war, so perhaps that's understandable. The 9th Cavalry spent the war in the Philippines, which was also a somewhat active ongoing responsibility for the Army. The 25th Infantry spent the war in Hawaii. While perhaps all of this is understandable, it is a bit odd under the circumstances.

Over 300,000 blacks entered the Army during the war as wartime volunteers, but most were assigned to support units, in a move that was to become the hallmark of the remaining days of the segregated Army. Still, some black units did see combat duty, such as the black 369th Infantry Regiment, a National Guard unit from New York. Black National Guard units had appeared in several states by that time, and it was more difficult to relegate these units to service roles, and it was also politically difficult to sideline them to roles that weren't part of the great effort in Europe.. Another such unit was the 366th Infantry Regiment, which was an all black regiment that had, very unusually, black officers.

Officers of the 366th Infantry Regiment.

While I have no strong evidence to support it, it is curious that a military resource that had been actively used in every American war since 1862 was sidelined to this extent during World War One during an administration that was headed by one of the most racist Presidents in our post war history. Woodrow Wilson, who is otherwise regarded as a symbol of the Progressive movement, was a product of the post Civil War American South and held very racist views regarding American blacks. The country seems to have slid backwards in this period, which also was witnessing the rise of the Klu Klux Klan. Wilson famously said of the revisionist Southern film Birth of a Nation that "it is as it was", which it clearly was not, and the sidelining of black troops during his administration is curious.

As noted above, black sailors served in combat roles during World War one, and even some recently retired black servicemen were recalled to service during the war, demonstrating their value to the modern Navy. They served in combat roles when called upon, like all sailors, but as noted, they were recruited as messmen and were exclusively enlisted men.

1919 to 1941

10th Cavalry, early during World War Two.

Black troops had been relegated, in many instances, to support roles during World War One, but where they were allowed to fight, they preformed very ably. The 369th, for example, was highly decorated during the war. None the less, the prejudice that really started to assert itself against black soldiers indicated something that was to set in and exhibit it self again in the nation's next conflict.

During the interbellum period, however, the Army seemingly returned to normal. The four black regiments returned to their normal duty and training and were fully incorporated back into their peacetime roles.

The Navy, on the other hand, did not return to normal. Departing strongly with its prior history, the Navy joined its subordinate branch the Marine Corps in completely prohibiting black enlistment in the Navy after World War One. The basis for this completely escapes me, but it would appear to reflect the very significant institutional racism at the time. This policy was reversed in 1932, but only to the extent that blacks were allowed to enlist once again as messmen, a role which was heavily populated by Filipino recruits at that time in sort of a special license granted to Filipinos. A long history of the Navy being relatively progressive on race relations thereby came to an end. Servicing black sailors were allowed to complete their careers in their roles, but new black sailors were relegated to the mess. From 1919 to 1932, there was no recruitment of black sailors at all.

Ironically, during the same time period a small exception to this progression on the sea took place in the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, a forerunner of the Coast Guard. From 1887 until his retirement in 1895 Captain Michael Healy served as the cutter of the Revenue Cutter Bear. At the time of his retirement in 1895 Healy was the third highest ranking officer in the Revenue Cutter Service. Healy was of mixed descent, but that mixed descent would have kept him from this role in the Navy.

World War Two.

Army mechanic. This type of role was the most common for American black soldiers during World War Two.

World War Two was in some ways to be a reprise of World War One for black troops for much of the war, but it did change as the war went on. At the start of the war, there was a conscience effort on the part of the Army to use blacks only in support roles, in spite of their being four standing black combat units. This only changed as the war went on, and really only towards the end and in ways that are small enough that much that has focused on these very real efforts has tended to exaggerate them to an extent.

World War Two saw a very high volunteer rate on the part of black Americans, which has sometimes been regarded as surprising but which shouldn't be. African Americans had started the process of immigrating from the South to the North during the prior two decades and the war accelerated that process dramatically, which also put them in a new context where prejudice, while very real, was less pronounced. Also, as a population, the sympathetic nature of a conflict to liberate oppressed peoples likely had a natural appeal to a population that had suffered oppression itself. Finally, there was a widespread belief in the black population that black service during the war would lead to the acceleration of the cause of black civil rights, which turned out to be a correct assessment.

The old black Regular Army units saw service, but in disappointing was to some extent. The 24th Infantry Regiment saw service in the Pacific throughout the war, making it a bit of an exception. The 25th Infantry Regiment was incorporated into the 93nd Infantry Division, an all "colored" unit, which was not sent to the Pacific until 1944 and which saw itself often being used in support, rather than combat, roles. The 9th Cavalry was used to supply replacements in the ETO, and therefore did not see combat as a unit and was disbanded in 1944. The 10th Cavalry Regiment suffered the same fate.

Soldiers of the 93d Infantry Division in Bouganville.

All of this was partially due to a belief by career Army officers that blacks made poor combat soldiers, a belief that does not seem to have been founded on anything. Late during World War Two, however, the shortage of infantrymen in Europe became so severe that the Army began stripping support units for combat soldiers and allowed black service troops to volunteer for combat duty, which they did in high numbers, even though it meant taking a reduction in rank to do so. Interestingly, while the intent was to deploy them in segregated units, one Southern officer misunderstood his orders and used them as conventional replacements, in spite of a personal belief in military segregation. While this was reversed once the mistake was understood, the experiment worked well and blacks integrated into largely white units did not prove to cause disruption.

92nd Infantry Division in action, Italy.

A few black combat units, such as the 92nd Infantry division, the 332nd Fighter Group, the 93d Infantry Division did see active combat service as the war went on, and black combat units had good combat records during the war.

Soldier of the 12th Armored Division with German prisoners. He carries an M1 Garand and a captured German ceremonial military knife.

The story for the Navy was somewhat similar, in that it saw the return of blacks to active combat service. Starting off the war being relegated to secondary service roles, as the war progressed blacks were reincorporated, on a segregated basis, into combat service. By the wars end it was the case that even two ships had all black crews and blacks had

The all black enlisted crew of a submarine chaser.

Black sailors of the USS Mason, a ship crewed by all black enlisted men.

Under pressure from the Roosevelt Administration, the Navy also commissioned a handful of black officers for the first time since the Navy's early history. The officers largely saw service limited to shore roles due to the segregated nature of the Navy, but at least one was assigned as an officer on board one of the two entirely black crewed ships.

The first black Naval officers during World War Two.

The Marine Corps broke with is prior history during the war, and enlisted blacks for the first time starting in 1942. In November 1945 the first black Marine Corps officer was commissioned. Marines served in service roles in the Marine Corps, but given the nature of the Marine Corps, that did place them into combat.

Black Marines on Saipan.

1945 to 1948

After World War Two, it could no more logically be argued that blacks made poor soldiers. Black units, and the very few other racially segregated units (such as those made up of Nessi soldiers), had proven effective in combat. None the less, it was only due to a bold move by President Harry S. Truman that military segregation ended on July 26, 1948. On that date he issued Executive Order 9981, which stated:

It is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall

be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed

services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.

This policy shall be put into effect as rapidly as possible, having due

regard to the time required to effectuate any necessary changes without

impairing efficiency or morale.

The move seems obvious now, but it shouldn't be taken that way. Racial segregation remained fully legal and very common in American civil society, and racist views were not only common, but largely accepted to at least some degree nearly everywhere in American society. It was a bold move and it was one that Truman didn't have to make. There was very little to be gained politically by it. But, while the integration wasn't instant, it did change things quickly and significantly. The era of a divided military was over.

Integration of the services was not instant, and interestingly it was not fully left to the services themselves. The first service to fully integrate was the U.S. Air Force, which had only come into existence in 1946 and which fully committed itself to integration, achieving it by 1949. The Air Force as a separate service inherited the structure of the United States Army Air Force, which would partially explain why there were segregated units in it, but it did accomplish the policy quickly. The Army, in comparison, took on the project piecemeal, but the Korean War was soon to change that.

1950 to 1990, the Cold War, with some hot ones.

There was an assumption in the immediate post World War Two era that the era of major wars was over. The use of the atomic bomb to end World War Two brought about an assumption that all future wars would be short, and nuclear. The assumption wasn't founded on reality at the time, and it would soon be proven to be wildly inaccurate.

The peace that ended World War Two didn't really bring about a global termination of war in the first place. It's popular to think of there being a gap between World War Two and the Cold War during which there was a short hopeful period of deluded peace, but that isn't really true. A civil war broke out in Greece before World War Two ended, pitting Communist against Anti Communist. Guerrilla wars followed in the wake of Soviet advances in World War Two as well, with some actually breaking out within the liberated areas of the Soviet Union itself. China's long running civil war broke back out. The US seemed to assume there'd be a peace, and a nuclear peace at that, but that was simply wishful thinking. That wishful thinking would be broken by the Berlin Blockade and then, shortly after that, by a new war, the Korean War.

The Korean War was the first war the United States Army fought with an integrated Army, and the process worked fairly seamlessly, although not universally so. Even though Truman ordered the service integrated in 1948, it was also the case that it didn't come about fully until the Korean War, and the Army entered the war with some segregated units remaining.

Soldiers of the 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea. The 24th remained segregated when deployed and was disbanded in 1951, it's reputation somewhat tarnished by performance in Korea that was later determined to be caused by poor leadership. The unit itself fought well prior to it being disbanded for purposes of integration. By this time, black draftees were going right into regular units so the 24th was an anachronism.

Following that, in the 1950s, the Army quickly became an American institution that was colorblind, and hence a good place for poor blacks to get a start or a career. Quite quickly the blacks became a significant demographic in the U.S. Army. This was reinforced during the Vietnam War, during which the economic demographic many blacks fit into meant that they were in the likely to be drafted category for the first of the two Vietnam era drafts. But by that time blacks were also becoming significant in the Army's officer corps. All this was true of the other services as well. And it remained the case all the way through the Cold War.

Vietnam, 1967.

Oddly, it was the Navy again where a hiccup occurred, although one that did not prove to be disruptive long term. Racial tension on board the USS Kitty Hawk erupted in what might be regarded as a near mutiny, or even a mutiny, lead by black sailors on the ship when it was ordered to return to service off of Vietnam after a long deployment. The ship had a large contingent of sailors who were enlisted under a wartime program that had brought in many who were below the general standards of the Navy and the entire service was suffering from poor moral in the late stages of the war. The riot was actually diffused by a black officer, at great threat to his own well being, although his actions resulted in the destruction of his career. This instances stands out as a singular example of a real mutiny on board a U.S. ship and a surprising one, given the era in which it occurred. It's also interesting that it occurred in the all volunteer Navy, where as tensions in the Army did not result in something similar.

After the Vietnam War, the service suffered in general from a tarnished reputation that the country now regrets, but it kept on being a haven for blacks to enter middle class employment and black entered the service in large numbers. Interestingly, it apparently isn't so much the case today. According to a recent set of articles I read blacks are decreasing as a demographic in the service. This appears to be worrying some people, but it probably shouldn't. Poor Irish and Germans decreased as a percentage of the service long ago. Hispanics are rising as a percentage of the service. All this means that the service continues to be a place where the poor often tend to get their start. If blacks are decreasing as a percentage of servicemen, it likely means that the service no longer seems as necessary to them as an economic opportunity as it once did, and that's a good thing.

.jpg)