We haven't been putting up that many newspapers recently, but if we had, you'd have noticed this occurring. The early winter of 1917-1918 was really cold.

Brutal Winter Weather Of December 1917 and January 1918

December 1917 through January 1918 still stands today as the coldest and snowiest December-January period ever recorded in Louisville, Lexington, Bowling Green, and several other locations across southern Indiana and central Kentucky. The 49 inches of snow that buried Louisville during those two months beats the 2nd snowiest December-January by more than a foot and a half!

And I mean cold everywhere. From the Mexico Es Cultura Site:

The hurricane season that hit the Gulf of Mexico usually starts between April and May and ends in November. Rarely there were extreme weather events of this magnitude outside of those months. However, according to the chronicles, in the coasts of Texas and Tamaulipas was recorded a strong hurricane at the beginning of January 1918.

The hurricane destroyed the poor houses of Tampico and flooded the city, as well as the towns of Nuevo Laredo and Laredo, Texas. The traditional neighborhood of Doña Cecilia was practically destroyed. On the other hand, a cold front from the glaciers of the North Pole caused severe snowfall in the cities of Monterrey, Saltillo, Ciudad Victoria, and San Luis Potosí, among other towns, mostly on the border side.

Local governments requested the help of President Venustiano Carranza to send medicine, food and blankets to help the most population in need.Cold in Wyoming too.

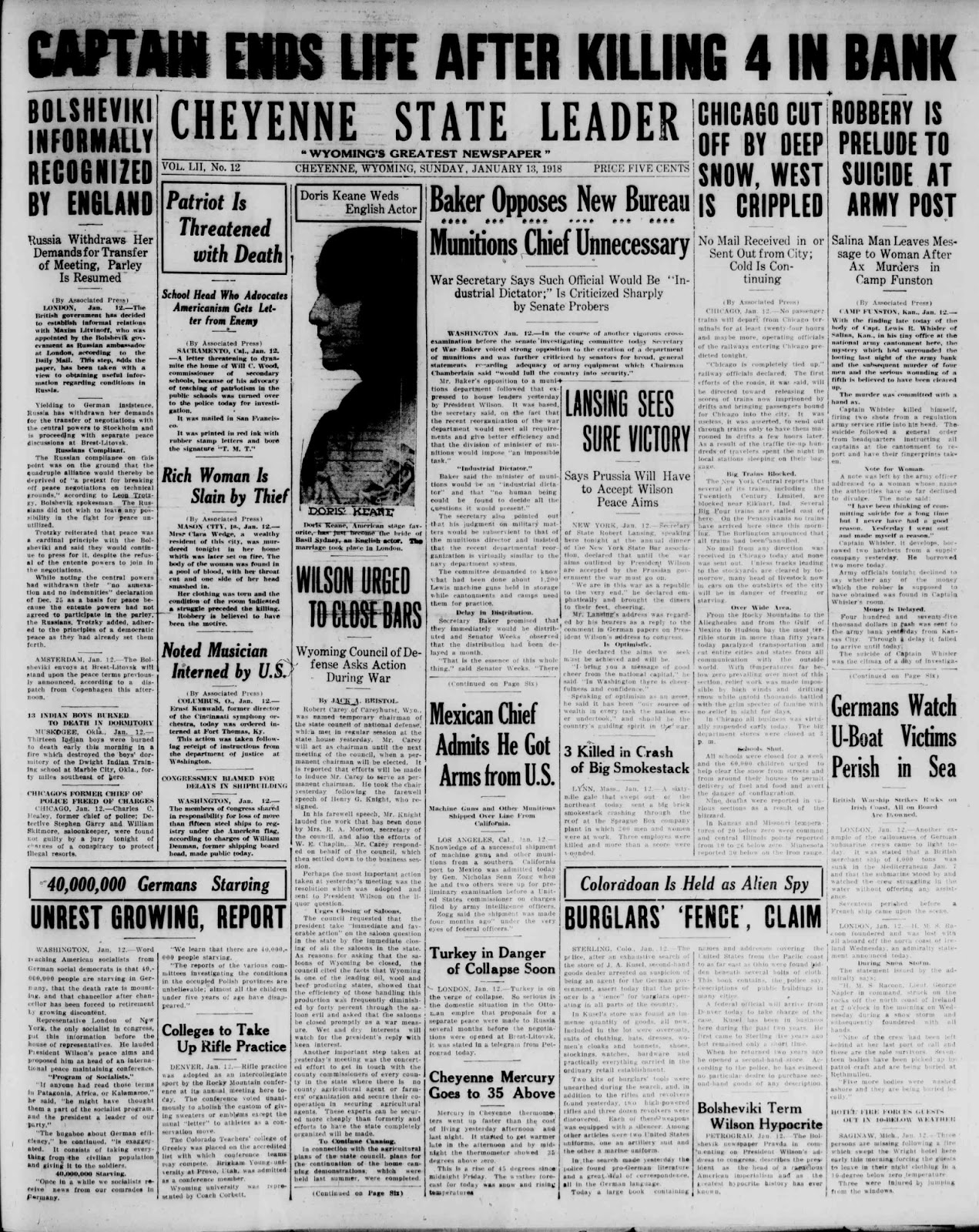

The Wyoming newspapers, or at least one Cheyenne one, had been making fun of the cold in Nebraska earlier in the week, noting how much warmer it was in Wyoming, when of course the weather changed, as it will, and the mercury dropped. For the second half of the week of January 8, 1918, temperatures were down in the negative range. Finally around this time of the week, after having been down that low the day prior, it looked like some relief was on the way.

The Cheyenne newspaper was noting temperatures were anticipated to go back up to above 35F, which shared placement with rifle practice being introduced to colleges. Bad weather got more notice however.

This sort of temperature would be brutal at any point, but it's easy to forget looking back a century at 1918, which shares mental familiarity with us today, that houses were heated much differently. We've dealt with this before, but today, most Wyoming houses are heated with natural gas, a clean burning efficient heating fuel. Some houses (like mine) are heated with electrical heating elements. In 1918, most houses in this area would have burned coal. Some houses would have been heated with wood fires, particularly rural ones. Indeed, even houses heated by coal would have been partially heated by wood cook stoves for a lot of the day.

By this period, I should note, major buildings started having boilers. And some, indeed a lot of, homes also had radiant steam heat as well. I'm really far from an expert on these even though they exist everywhere to this day, but generally they require a boiler and that requires a fuel. Around here, today, the fuel is natural gas. In other places it remains heating oil. At that time it would have meant coal. So when we speak of a house being heated by coal, we don't mean simply burning coal for heat, although I've been in modern houses where residents did just that, or in shops where the owners did just that.

Burning coal for heat entails some factors that we don't consider here in the West much, but those who still use heating oil in the East probably do. For one thing, you have to order it and store it. The poster above from World War One shows that this was a concern pretty far in advance of winter. And at least according to my mother, who recalled their coal furnace in Montreal, fleas came with the coal for some reason.

And of course, coal smells when it burns. Almost any town would have been smoky in the winter. Here in Wyoming people often lament the winds during winter, but I have to wonder if some wind (not enough to blow the furnace out, which can happen, weren't welcome as they'd blow the smoke out of town.

That would have meant, fwiw, that most towns would have had a smokey haze above them all winter. Indeed, one thing I didn't like about Laramie when I lived there was all the wood smoke, as so many students burned wood at the time, and I still don't like that. It's one of the reasons why I've resisted a wood burning insert in my own house for so many years, while my wife, who grew up with them in rural conditions, would like one.

"African American schoolgirls with teacher, learning to cook on a wood stove in classroom." This is an odd photo put up here only to illustrate a wood burning cook stove. Using these is much different than using a modern electric or gas oven, but I have to suspect that most of these girls learned as much about cooking at home as they did in the classroom. Having said that, Home Economics remained a class a lot of girls took when I was in junior high in the 1970s.

For a lot of the day, in almost every home occupied by a family, or in every boarding house, the kitchen was putting out heat via a cook stove. Cooking with a wood burning stove is generally fairly slow, so what this meant is that the stove generally burned for hours. Chances are that in a lot of homes the fire was stoked right around 4:00 am or so, or certainly not later than 5:00, in contemplation of cooking a meal about an hour later. The heavy cast iron stove would put out heat for at least 30 minutes if not an hour after it was last stoked, so kitchens started likely heating up around 4:15 and stayed that way until at least 7:00, if not until 9:00. In many homes the heating process would start again around 11:00, if children were at home or if a male occupant returned to his house at noon. Most men likely didn't, so the stove may have remained cold or lukewarm during the mid day but get stoked back up around 3:00 in anticipation of serving around 6:00. Cooking was slow. Some such stoves on many days would have been fired back up much earlier, depending upon what was being cooked for that evening. And the stove likely burned to a degree until 7:00 and started getting cold around 7:30.

A lot of business establishments of various types would have had a stove as well that they kept running basically all day long.

So, lots of wood smoke to add to the coal smoke. Neat.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Related threads: Cold then and now.

No comments:

Post a Comment