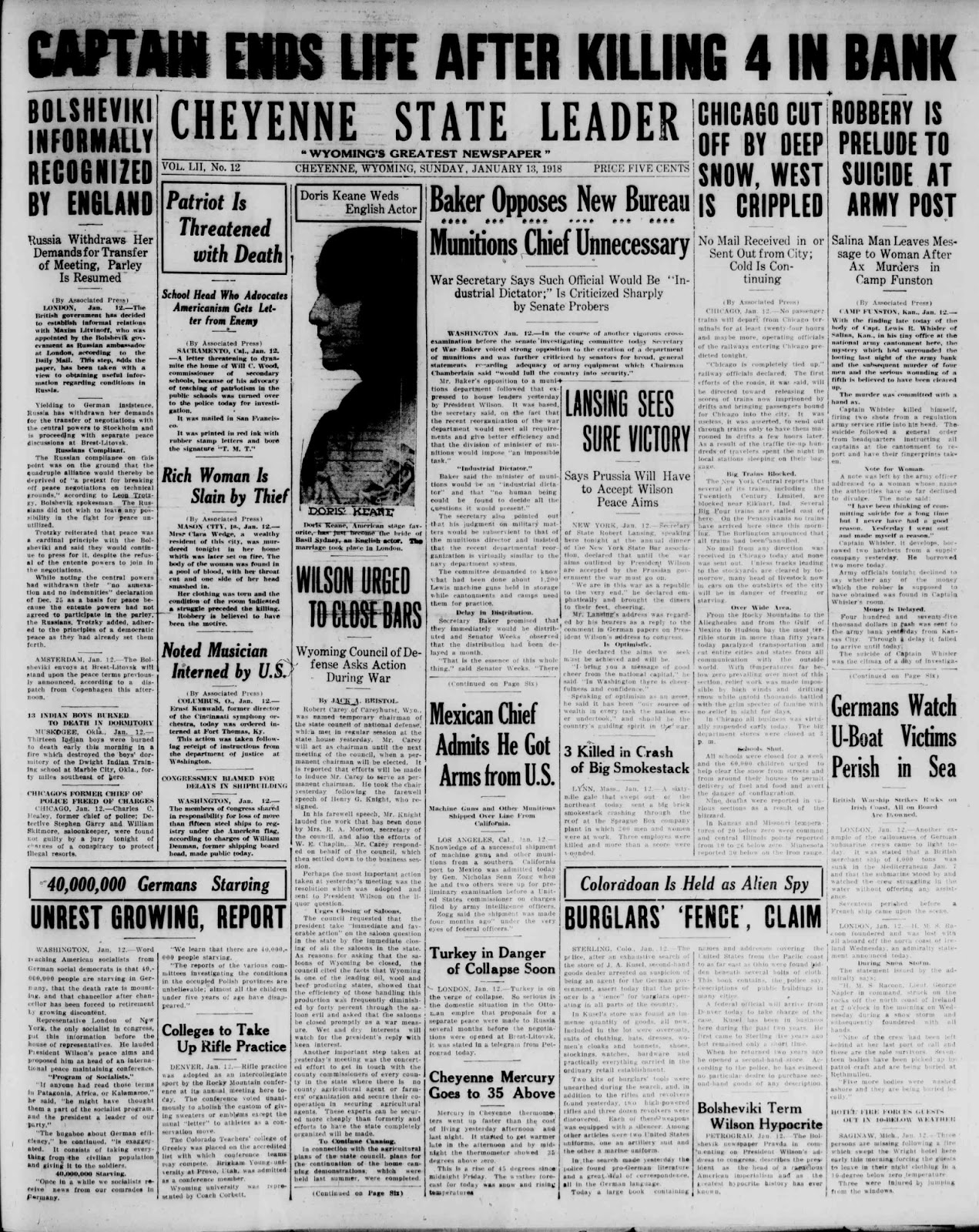

John Henry Cardinal John Newman, Anglican intellectual and Priest. . .and later Catholic Cardinal.

I am not a theologian and this is not an evangelizing post, at least not by intent. In this post I do not intend to advance any theological or religious view, nor do I wish to condemn the theological views of anyone else, except to the extent that those views depend on a false version of history that's demonstrably false. And some people's do. If the history doesn't support their view, they have to do something to reconcile their view with history, in my opinion, but that doesn't mean that you alter the history to make it fit your view. You have to accept the historical baseline. As Adams stated in the quote set forth above;

I am at least an amateur, and published, historian, and that's what motivates this text. I have no degree in history, but I have very close to a Bachelors of Arts in History that was solely through picking up history classes while studying for my Bachelors of Science.* I also have a JD, as folks here no doubt know, and while a JD isn't a degree in history, it can be (and frankly should be) short of an ancillary degree in philosophy and social history, to a student who has an active enough mind to appreciate it. I have been cited in history text as an authority on certain things (usually cavalry) and have been published in book form once and in magazine form more than once, although not always on history by any means. So, those are my creds, I guess.

In doing that one thing I've always done is to try to determine the history of things as they were at any one time. I don't appreciate the all too common reinterpreting of history to fit modern views, and feel you have to accept history as it actually is and was, and as viewed and appreciated as it occurred. In other words, I don't appreciate reinterpreting the motives of people of the past to fit modern views, as it supports our modern views, which will soon cease to be modern, and which will often come to be regarded as odd at a later time.

Okay, I've noted that all before. So why am I treading into such uncomfortable waters now, that being the history of the Church?

And by the Church, I mean Christianity. But when people use the term "the Church" to define Christianity, it's not an accident. For most of Christian history there's been one Church, and that Church still exists today.

Well, my entry into this touchy field has to do, part, with having received a video from a friend and then seeing some of the really ignorant (and even mean and hostile) posts that were put up in connection with that. The video is one that I wouldn't normally have come across (thanks Lyndon), so normally I wouldn't have strayed into this area

First, however, listen to the video.

And that's because Christianity started as an Apostolic faith and remained so fully at least up until 500 years ago.

And here's where things get so confusing for people who don't grasp the early history of the church.

There are a lot of Christian Protestant congregations that like to say that "we're just like the early Christians". They aren't at all as a rule. There are some Protestant denominations that do claim Apostolic succession, however, but they're rarely the ones that make that claim. So what does that all mean?

Now, some here have noted from time to time that we've used the term Apostolic Churches here fairly frequently. And here's where some American Protestants will immediately try to dissent, but in truth the only good argument that this supports is the ongoing one between the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church. It doesn't support any argument in favor of the type of Protestantism we are discussing here at all, although again, Anglicans and Lutherans can jump in it in an informed fashion.

The early Apostles all formed "churches", with in the greater Church, where they went to spread Christianity. Those places had, as their center, various cities, and again right from t he onset these became Apostolic Seats. So, for example, we had Jerusalem, and Rome, and Constantinople.

But all of these Apostolic Seats were in contact with each other, in greater or lesser degrees, for a very long time. And the thing about them is that they were all part of the same Church. About this, there is no doubt. Just none.

And they all took the same general position on key matters, the same being the structure of the Church (bishops, priests, deacons, etc.), the requirement that only Bishops could ordain Priests (they did, there's no doubt) and the central role of the Sacrifice.

Even elements that popped up endorsing heretical positions often agreed on these things, we'll note. So, for example, Nestorians or Gnostics didn't dispute that.

So, for about 1,500 years all Christians agreed that only Bishops could ordain Priests. Bishops could only be appointed by the the Patriarchal Bishops of their branch, although this gets a bit complicated. Only Priests could forgive mortal sins. Only Priests could consecrate the Sacrifice. Catholics, the Orthodox, most Anglicans, all still hold those positions. Some Lutherans hold positions identical or very close to that.

And for nearly that long long there was one Church.

And that's why disputes between the Orthodox and the Catholics on "the original church" can only really be understood in their context. When Catholics and Orthodox debate that, they don't really suggesting that the other sprung up at some point in the 1400s or something like that. They both agree, as do the Lutherans and the Anglicans, and at least some of the Methodist, that up until 1054, more or less (although it was repaired briefly in the 1400s) that there was just one Church.

Assumption of the Theotokos Greek Orthodox Cathedral of Denver. The Bishop who presides here can also trace his seat back to one of the Apostles, just like in the example of the Catholic Cathedral depicted above.

Now, that gets confusing to some not familiar with that Church, or indeed the modern Catholic or Orthodox Churches, as while there's only one Church, there are smaller churches within them, and there have long been. The Church early on recognized different Rites that were unique to various regions and there were also various "churches" within the Church, and there still are.

So, for example, there isn't any Roman Catholic Church really, as the Catholic Church doesn't use that name. There is a Latin Rite of the Catholic Church, which is what most people think is the Catholic Church, but which is just one Rite in the Catholic Church. There were, prior to 1054, various Eastern Rites, and there still are. It's complicate following the schism of 1054 however as some of those Rites, but not all, went into schism, if you take the Catholic view, or if you are in an Eastern Orthodox Church, you'd take the view that the Catholic Church did. Since that time, some of the Eastern Rite churches have come back into communion with the Catholic Church thereby terminating the schismatic problem between those Rites and the Catholic Church, in their view.

To further compound this situation, and important from a historical point of view, while many people are familiar with the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Churches, not nearly as many are familiar with the six Oriental Orthodox Churches. As we'll see in a moment, these churches stand alone due to early physical separation from the Church and now stand as Orthodox Churches that are not in communion with Rome, but they aren't the same as the Eastern Orthodox.

Anyway you look at it, however, (and we'll get to that in a moment) the Orthodox Churches and the Catholic Churches all recognize almost everything about each other as fully correct, with a few exceptions, which will look at in a moment. That is, they all agree the Bishops and the Priests of the others are valid Bishops and Priests. They all agree that their Bishops have Apostolic Succession. They all agree each others sacraments are valid. They frankly disagree on very little. To the extent they do disagree, the Eastern Orthodox and the Catholic Church disagree on so little that its almost impossible for an outside observer to figure out what they in fact disagree on. There's a little more that can be understood, if a person has a theological frame of mind, that's not agreed upon in regards to the Oriental Orthodox, but ironically that's true universally. I.e., the Oriental Orthodox theological disagreements apply not only to the Catholic Church but to a large extent to the Eastern Orthodox as well. This is due, principally, to the historical fact that the churches that became the Oriental Orthodox (keep in mind that at the time there was no division between these churches at all) couldn't send delegates to later councils, as it had become practically impossible, and thereafter they did not, therefore, benefit from resolutions and clarifications that were made at those conferences.

Before we move on, we'd note that even the terms "Catholic" and "Orthodox" here can be really confusing, however, as amongst themselves both the Catholic and the Orthodox use them differently. All Christians use Catholic to some extent the way it was originally used, as found in the Nicene Creed:

The Nicene Creed

I believe in one God,

the Father almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

of all things visible and invisible.

I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ,

the Only Begotten Son of God,

born of the Father before all ages.

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father;

through him all things were made.

For us men and for our salvation

he came down from heaven,

and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary,

and became man.

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate,

he suffered death and was buried,

and rose again on the third day

in accordance with the Scriptures.

He ascended into heaven

and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory

to judge the living and the dead

and his kingdom will have no end.

I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life,

who proceeds from the Father and the Son, (or in the Orthodox and Eastern Rite Catholic Churches, "who proceeds from the Father)**

who with the Father and the Son is adored and glorified,

who has spoken through the prophets.

I believe in one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church.

I confess one Baptism for the forgiveness of sins

and I look forward to the resurrection of the dead

and the life of the world to come. Amen.

Both Catholics and the Orthodox use the term "Orthodox" to refer to its plain and ordinary meaning. So you'll have Catholics talking about somebody or some Parish as being "orthodox". And both the Eastern Orthodox and the Catholic Church have Rites that confuse some as being in the other group. There are a lot of Eastern Rite Catholics of various churches, for example, who use the same liturgy a the Eastern Orthodox churches do. Conversely, while they are small, at least some of the Eastern Orthodox churches have established Latin Rite liturgies within them to serve those who would prefer to be in the Eastern Orthodox churches but use a Latin Rite. If all that seems confusing keep in mind that the Catholics and Eastern Orthodox all agree there was only one church prior to 1054 and they all agree that after the split that they other group in the split remains a valid church.

Before we move on, and as an item of historical importance, for those who challenge this view, which is to be anti historical, as noted, it's also to be anti archeological. We noted the six separated Oriental Orthodox Churches, all of which have their origins in the East. If early Christianity was truly different from what we've just stated, in spite of all the writings and texts we've noted, we'd expect them to have really different practices as they were separated They were only able to attend the very early councils for this reason and one of them, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church has the largest Bible as a result, as it was not able to send delegates to the later councils that fixed the Canon of the Bible. Anyhow, nope, their practices are exactly the same as the Eastern Orthodox and the Catholics in every sense. So, here too we find that the history fits the archeology, and these islands of Christianity in the East keep on keeping on with the exact same practices and the exact same understanding on those practices as the other Apostolic Churches. Their Bishops consecrate Priests, the Priest offer the Sacrifice of the Mass, and Confession, etc., and they all have the same understanding of what that means theologically.

Saint Mary's Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, Denver Colorado. This is a church, not a Cathedral of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, a Oriental Orthodox Church long separated from the West. However, like the other churches mentioned here, the Priest serving here were ordained by a Bishop who can trace his seat back to an Apostle and the services here, while they would seem exotic to most Catholics and many Eastern Orthodox, are none the less pretty recognizable to both.

We should probably go further and note that this is also true for "Saint Thomas" Christians in Indian, or Armenian Christians in Armenia. Both populations were very long isolated, particularly the Indian one, from everyone else and yet we find the same set of beliefs and practices amongst them. In modern times they've split into the Orthodox and the Catholic groups, as they came into contact with the other churches, and yet the points we've set out remain valid about history and archeology.

And everyone agreed, including Martin Luther and King Henry VIII, that all of this was correct (although Martin Luther and King Henry VIII probably had a poor understanding of there being Oriental Orthodox Churches). That is, Lutherans, Anglicans and Methodist had no disagreement with anything set out above, and they all understood this history to be correct and what it meant to be correct. They still do, in large part.

St. Matthews Episcopal Cathedral, Laramie Wyoming in the 1980s. While the Orthodox and the Catholic Churches would dispute the validity of the ordination, the Bishop whose seat this is (the Episcopal Diocese of Wyoming is actually administered out of Casper) can trace his lineage back to an Apostle. As this isn't a theological treatise, I'm not going to get into the topic of the validity question.

So what happened?

Now, some of this would get into theology, and we're not going there, so we're only doing to deal with the history. Take your theological debates, if you want one, elsewhere.

What happened is that in 1517 Martin Luther, who was a Catholic Priest, got into a theological debate with the Church and ultimately, because of political reasons, some German princes sided with him, while others did not, and those who sided with him left the church and formed a new one. Now, that is not, no doubt, how Lutherans exactly see it, and that's okay as we're not debating the validity or invalidity of his actions. Only that it did happen. But whatever happened, Luther did not challenge the historical facts that preceded him, and nor do modern Lutherans. To the extent that it creates a historical problem for Lutherans it would be in that no German bishops followed this severance, and therefore Apostolic succession was clearly broken in German. In Scandinavia, however, this was not true as at least some Swedish Bishops did follow the severance, although its not really clear that they knew they were doing that. Not that this matters for our discussion.***

St. Paul's Lutheran Church in Denver which can legitimately be regarded as radically liberal and outside of the mainstream of the Apostolic Churches. While extremely liberal in its theology, it's oddly also attempted to attract disaffected extremely liberal Catholics by offering a service that's essentially identical to the Catholic Mass and broadly hinting, at the same time, that it has claims to Apostolic Succession, although this is very much complicated in the case of the Lutheran Churches.

Following this, of course, in 1536 Henry VIII took the same route, but in doing so it appears that what this at first caused was actually a schism, not a real break, as he and the English Bishops, all of whom followed him (not all the Priest did by any means, and many of the laity did not) didn't propose any theological innovations, contrary to Luther. That came later, during the Elizabethan period. And as noted, Methodists, who were a movement within the Anglican Church, also agreed with the Anglican Church on the history of the Church for the most part. Where Anglicans and presumably Methodists disagreed was on a topic which actually makes more sense for the Orthodox. I.e., they argued that they'd always been separate churches and not subject to the Bishop of Rome, which was clearly historically incorrect.****

I suppose that has to take us back to the schism between the Catholics and the Eastern Orthodox, or perhaps the Orthodox in general. This is a complicated topic but, after you dispose of most of it, and most of it can be disposed of, what you are left with ins the role of the Bishop of Rome. The Catholics assert that he's the head of the entire Church in a definitive sense. The Orthodox hold that he's the legitimate Bishop of Rome but that he's the First Amongst Equals. I.e, his opinion should be weighted more heavily, in the Orthodox view, but not override the independence of the other Apostolic seats.*****

And that's a theological argument I'm not going into.

So what's important about all of this?

Well this. People who argue about the nature of the early Church are simply flat out wrong if they don't accord the fact that there was just one church, and that it has in fact continued on. Nobody who takes history seriously can conclude anything other than that the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Churches are a straight line back to that one single church, and that they split around 1054. Some can and do argue that this is also true for the Lutherans, Anglicans and the Methodist. People who argue that their own church, if it isn't one of these, is the "original church", are in error.

A person might want to argue that there's some reason that their church is valid, and I'm not arguing any of that material here. But if you are going to argue about the "original church", well the original church is still here. You can argue whether the Catholic Church or the Orthodox Church are the original church, but when you are doing that you are really conducing a debate about the "two lungs of the church", as Pope Benedict put it. You can further make the argument about the Lutheran Churches or the Anglican Churches, but that argument, while it can be made, is more strained.

So how come we hear the other arguments made?

Well, we hear it made as the world of the 16th and 17th Centuries was in turmoil and information was really hard to come by. So that left a lot of room for people to develop their own theories in the vacuum of historical ignorance.

And that's why people in some camps are so touchy about this today.

And it all has to do with the Law of Unintended Consequences.

When Luther wrote his 95 Thesis (he didn't really nail them to the Cathedral door in Worms), he had no intention of challenging history or disagreeing with it. He probably, at that point, had no intent to start a separate church for that matter. It's certainly the case that when King Henry VIII declared himself to be the head of the Church in England, he meant just that. Not head of a separate church, head of

the Church. Indeed, he was quite opposed to most of the more radical Protestant thought at the time. But then

Holscher's Fourth Law of History stepped in.

What neither men contemplated was the impact of war and strife and its impact.

A common assertion regarding Martin Luther is that the Reformation got rolling as he translated the Bible into German and with the new invention of moveable type, now everyone could read it and come to their own opinions on things. That's right only by half, if that much.

In actuality, Gutenberg had invented a press with movable type, but that hadn't exactly been the day prior to the Reformation. Indeed, Gutenberg had been dead for over forty years when Luther got the Reformation rolling. And Luther's translation of the Bible, contrary to widespread belief, wasn't the first one that translated the Bible into German. But what did occur is that literacy was increasing in this period of time as the price of books was going down. Having said that, literacy wasn't exactly at sky high rates either. So the common assertion that the common man could now read the Bible was not really accurate. For that matter, the common assertion that the Catholic Church discouraged the reading of the Bible is also false. Most people just couldn't read, even during the Reformation.

But more could than had probably been able to at any time since the Fall of Rome, although the educated classes, which were more numerous throughout the Middle Ages than generally supposed, had always been literate. But what really got the anti historical actions we've been discussing here rolling is that turmoil caused by the endless wars that the Reformation touched off.

A rather odd painting of the victory of Gustavus Adolphus at the Battle of Breitenfeld in 1631.

Luther hadn't intended to kick off a general European War and King Henry VIII certainly wasn't hoping for one, but the combined impact of the political desires and forces of the day operated such that, particularly in Germany, various political figures aligned themselves with "reform" in order to gain greater political power. Europe slid into decades of incredibly bloody warfare, often inappropriately branded as a religious war as its origins, while incorporating the Reformation within it, were very political as well. Indeed, a person is perfectly entitled to be cynical about the degree of religious zeal of the princes leading armies in the cause of the Reformation north of the Rhine.

War, as we've previously noted, changes everything, and one of the thing it changes for a time in the influence of order. That's true of nearly every war. And it certainly was true of one as corrosive and violent as the Thirty Years War and its companions. Characters like Luther and King Henry VIII had not sought to through all of society into turmoil, but they did. And with that, and with the rise of print, it now meant people educated enough to read started to do just that and to interpret the Bible with an understanding of it that was not all that much different than the Islamic interpretation of the Koran.

For the entire history of Christianity past the Apostolic Age and prior to the Reformation, the books of the Bible were understood to be those texts written by Inspired Authors, as determined by the Church. That is, very early in the Church's history there had been an effort to determine which writings were divinely inspired and which were not. Unlike the Koran, there was not simply a text which was, and that was determined to be the Word of God. Various books were in use by the various churches (small c) around the Christian world. At some point early on the process began to distill down those books which the Church regarded as divinely inspired. This took quite some time but it is usually noted that the Church accepted the Canon proposed by St. St. Athanasius at the Council of Nicea. He, it should be noted, was an Egyptian Bishop, so before people get their backs too arched up he wasn't coming from Rome. He came from Alexandria. This would show, once again, both historical and archeological support for their being just one church, as we see an Egyptian Bishop, whom the Coptic Church (one of the Oriental Orthodox Church's) regard as one of their own, being massively influential at the council. That's the one, we'd note, where the Nicean Creed defined the Church. Not churches, the church. At any rate, the Canon of the Bible was basically accepted from that point (we'd note that at least one of the Oreitnal Orthodox Churches couldn't make it, and hence they have a larger Bible today) although confirming and defining that would in some ways have to wait until the Council of Trent.

Anyhow, what is important here is that the Church itself was the one that regarded itself as being able to define what was properly in the Bible and did so. At the same time, the Church had, long before that, already adopted, and had adopted right from the onset, practices that are referred to as Sacred Tradition. So, individuals today who argue that a person must refer only to the text of the Bible in order to know what is Christian are taking a position that is oddly out of sink with history, as the Church itself determined what was properly in the Bible. That is, if you accept that the Bible is inspired text, you pretty much have to accept that the Church had the ability to define and legislate what was inspired text. The Bible itself, of course, never says anywhere that a person should only read the Bible and disregard everything else.******

Anyhow, most of the newly literate of the period and many of the even old literate didn't have that kind of knowledge on anything, so the logical assumption in the turmoil of the 16th and 17th Centuries, for some of them, was that "I can just read the Bible and figure it all out for myself".

Now, at this point, we're getting back on the perimeter of theological topics, and I don't intend to do that. So I'm not going to argue that point in any fashion. I'll simply note, once again, that the understanding of everyone prior was that the Bible was inspired text but that you also had Sacred Tradition and you also needed properly ordained Priest and Bishops to proclaim the world of God, although average people cold proclaim it within the context and missions of their lives. Some, but not all by any means, of the new Protestant rebels argued, largely in ignorance of Church history, that they could do it as well as anyone else.

Now, there are certainly those who take that position today, and I don't care to argue with them as this is a history blog, not a religion blog. But that takes us back to history and anti history.

At the time, and on to today, those who argue for the validity of Christian churches that do not have, or do not claim, Apostolic Succession have a huge theological problem. Confronted with history, their only options are; 1) claim the history is wrong and argue for a false one; or 2) claim the history appears to be right but its secretly wrong; or 3) ignore the history. Of these three approaches, only the third one is intellectually valid here as the history is so clear. But historically, all three approaches, and in particularly the first one, has been the most often taken. And that's why the first one comes up in vehement form today, and often in the same quarters that feel compelled to not only argue for a false history, but to condemn the actual history and what it stands for, and often to also condemn science as well. It is, in essence, an anti intellectual approach to the validity of their faiths, but because its contra historical and anti intellectual, it's based on the thinnest of support and therefore subject to spectacular failure in the modern world.

In the Renaissance world this was less true as information was so much more difficult to come by. So, as a result, the supporters of various dissenting groups could and did make up what basically amounted to fables for early Church history. Ignorant of the surviving works from the early Church, which are astounding numerous, they just created new mythological histories that weren't supported by anything. Nobody can really blame the average man for believing them as the average man wasn't educated at all. So we ended up with groups like the Puritans, who really aren't very admirable in an assortment of ways, who were radically opposed to Christian history, as well as being radically opposed to every other Christian faith they ran across, which isn't surprising as the ones they were running across were the Anglican Church in England and the Catholic and Lutheran Churches in the Netherlands.

All of this is perfectly understandable. . . until you reach the modern age. Now, for the first time in history, accessing the early Church is super easy and it puts that approach into the dustbin. Now, a person, or rather a Christian, either has to accept that; 1) the early Christians were right and Apostolic Succession is necessary, in which case a person has to join a Church claiming Apostolic Succession; or 2) the early Church was simply wrong and Apostolic Succession, and all that went with the early Church and its ordinations and sacraments, really never mattered. . . not even in the Apostolic Age; or 3) it does matter, but there's a method and means by which it can be recreated even if there was a break in it, in some fashion. Or, you can just ignore it, if you are a Christian, and hope for the best. Most sincere Christians don't take that latter approach, if they become aware of this topic, which of course most never do.

More than a few do, however, like the Videoblogger we started off with, and this has had some really interesting results.

Perhaps the most interesting one I'm familiar with is a Fundamentalist Protestant congregation that went on a dedicated program of study in order to be like the early Church. In doing that, they concluded that the history left them no choice, and they converted in mass to Antiochian Orthodoxy, that branch of the Eastern Orthodox whose historical seat was in Antioch. That's a bold thing to do, but they studied the texts and made their determination, electing to go to that branch of Christianity whose Apostolic Seat was where Christians were first called that.

That story is more common than a person might suppose, although its a particularly notable example. Plenty of individual examples exist as well. For example Father Dwight Longnecker, a blogging Catholic Priest started off as an American Evangelical before he was ordained an Anglican Priest in England and then went on to become a Catholic Priest. Well known Catholic Apologist Jimmy Akin started off as an anti Catholic Fundamentalist Protestant before his studies lead him to conclude that either Orthodoxy or Catholicism were the true original churches and he had to decide which one to go to. Steve Ray, another well known Catholic apologist, was a devout Baptist until he studied the Church Fathers and concluded he had to become a Catholic. Less well known to Americans but widely know to Europeans, Ulf Ekman, a Swedish Pentecostal mega pastor, shocked his congregation (one of the world's largest) in 2014 when he announced that he was converting to Catholicism, specifically noting that his studies of Catholicism lead him to conclude that many of the beliefs he held about it in (still) anti Catholic Sweden were simply flat out wrong.

So, is this then an evangelizing post arguing that you must do the same? No. What this post argues is that we don't get to make up history to suit our views. This is an area in which, since the Reformation, people have been doing that but there's now too much easy information available to credibly do that. People don't get to re-write history to suit their views, whether that's a religious view, as discussed above, or a cultural view, as in the false claim that the Civil War wasn't about slavery. If that makes them uncomfortable, it's up to them to examine it and see what that means, but what it doesn't mean is that a person gets to alter the past.

________________________________________________________________________________

^That comment alone may have inspired this post, even though it has nothing to do with the actual material addressed here. I'm sick of that sort of tone. You don't get to go around claiming to be advancing the goals of Christianity by calling an obviously fairly devout Protestant young woman a bimbo just because she dresses like modern young women do and happens to do so in a video sympathetic to the Catholic Church (she did the same for the Orthodox Church).

*I'd note that respected historian Barbara Tuchman also lacked a degree in history. Polymath Victor David Hanson also lacks a degree in history, having one instead in Classics.

** The Filoque, i.e,. whether the text of the Nicene Creed should be read as:

"who proceeds from the Father and the Son."

Or:

"who proceeds from the Father"

is one of the two actual enduring disputes between the Orthodox and the Catholic churches. Be that as it may, in the Greek version of the Nicene Creed used by Eastern Rite Catholic Churches the text is identical to that used by the Orthodox Churches and the argument can be made that the actual understanding of the meaning of the sentence is identical. The text has not been a sufficient barrier to prevent various Eastern Churches from coming back into communion with Rome over time, including at one time the entire Eastern Orthodox Church for a while in the late 1400s (it left again) and large sections of the Russian Orthodox Church until strife reversed that.

***The Lutheran Church is fairly split today as well, although I don't know enough of the history of that to really address it. In the US there are two principal bodies of Lutherans which is at least in part due to some being of Scandinavian origin and some of German origin, although in modern times there have been splits based on whether a group is "liberal" or "conservative".

****At various point some people have claimed that as Christianity was in

fact established in Great Britain prior to the evangelizing mission of

St. Augustine, and moreover that there were even Bishops serving in

Great Britain prior to his arrival, that the Church in Great Britain was

an independent Apostolic Church early on. The problem with this

argument is that the Bishops serving in Great Britain were Catholic

Bishops. It is true that they had some slightly different practices than

those which came in with St. Augustine and his companions, but this

shouldn't be surprising as there sufficient differences in the Catholic

Church then and now that there are more than one Rite in the Catholic

Church, including even now two rites in the Latin part of the church.

Upon St. Augustine's evangelizing mission bearing success a local

council was held and the few differences that existed in matters like

calendars were quickly resolved in favor of those used more broadly in

Europe.

***** The Eastern Orthodox have endured at least one schism themselves since this separation in that the Russian Orthodox Church split a bit over certain matters which resulted in the minority "Old Believers". This is a really complicated topic but Old Believers took the topic of Apostolic Succession so seriously that, unlike German Lutherans, their priesthood simply expired and ceased to exist. In modern times, seeking to end the suffering that entails for them, some of have had priests consecrated by Bishops willing to do that and so some Old Believers once again have priests.

******As another historical fact, not capable of being disputed, the Catholic Church, by which in this context we mean the one Catholic Church prior to the 1054 Schism, set the Canon of the Bible. When people claim solo scriptura as the basis for their beliefs they'll sometimes try to excuse that, but its a fact. Again, I've seen the one odd website above try to do just that, by claiming that the books of the Bible were in use by various churches in the ancient world before that, to which the more knowledgeable debater agreed, because its correct, but then went on to note how they were set. At that point, the debate broke off.