The price of oil has now fallen so low shippers are now choosing to go around the Horn of Africa, and burn the extra fuel, rather than go through the Suez Canal and pay the fees for doing so.

Incredible.

Ostensibly exploring the practice of law before the internet. Heck, before good highways for that matter.

Monday, February 29, 2016

Blog Mirror: The Ranger Station: The History of the American 4x4

A website devoted to Ford Rangers has The History of the American 4x4 on it. Some neat photographs are there, and an interesting history.

I've covered that here in a couple of posts, including:

And also:Truck Train, May 1920.

We have, in this continuing series on transportation, looked at trains, planes, ships, and shoe leather. We're going to start looking at the type of transportation now that's just part of the regular background of our lives, for most of us. Automobiles.In doing this, I've broken the topic up into two, and perhaps oddly, I've started with trucks and lorries. That probably seems backwards, but for what we're doing it really isn't. Transportation by truck has been a major change in the basic distribution system for the nation.

When I seemingly had more free time, I used to occasionally publish articles in various journals. This posts has its origins in one such article, which came about, as a concept. right about the time that I became to busy to really keep at that endeavor, so I never wrote it. Perhaps, if worthwhile, I'll develop this blog entry into an article later. I'd also note that this is a topic which I've actually posted on here before. And its a topic I consider every year during hunting season. The topic of back country travel, and indeed travel in rural areas in general.

Labels:

4x4,

Automobiles,

Blog Mirror,

Transportation,

Trucks

Is Warren Buffett reading my blog? Buffett's letter to his shareholders.

Buffett says, probably a lot more succinctly, what I was posting on yesterday in his annual letter to his shareholders, which I lucked on by way of the New York Times.

So what does the Oracle of Omaha allow?

And he goes on:

So what does the Oracle of Omaha allow?

It’s an election year, and candidates can’t stop speaking about our country’s problems (which, of course, only they can solve). As a result of this negative drumbeat, many Americans now believe that their children will not live as well as they themselves do.

That view is dead wrong: The babies being born in America today are the luckiest crop in history.

American GDP per capita is now about $56,000. As I mentioned last year that –in real terms –is a staggering six times the amount in 1930, the year I was born, a leap far beyond the wildest dreams of my parents or their contemporaries. U.S. citizens are not intrinsically more intelligent today, nor do they work harder than did Americans in 1930. Rather, they work far more efficiently and thereby produce far more. This all-powerful trend is certain to continue: America’s economic magic remains alive and well.

Indeed, most of today’s children are doing well. All families in my upper middle-class neighborhood regularly enjoy a living standard better than that achieved by John D. Rockefeller Sr. at the time of my birth. His unparalleled fortune couldn’t buy what we now take for granted whether the field is – to name just a few – transportation, entertainment, communication or medical services. Rockefeller certainly had power and fame; he could not, however, live as well as my neighbors now do.Though the pie to be shared by the next generation will be far larger than today’s, how it will be divided will remain fiercely contentious. Just as is now the case, there will be struggles for the increased output of goods and services between those people in their productive years and retirees, between the healthy and the infirm, between the inheritors and the Horatio Algers, between investors and workers and, in particular, between those with talents that are valued highly by the marketplace and the equally decent hard-working Americans who lack the skills the market prizes. Clashes of that sort have forever been with us – and will forever continue. Congress will be the battlefield; money and votes will be the weapons. Lobbying will remain a growth industry.

This really touches on the matter of economics, political rage, and perceptions that I touched on yesterday. And whatever a persons feelings or perceptions are on any of these, Buffett, who is long lived and very experienced, can't easily be dismissed.. I think the reasons for the perceptions are explained below in my post, but the anger out in the voting booth this year can't be disregarded either. Someone has famously said the medium is the message, but either the messages both ways are confused, or our a general condition that is causing upset isn't generally understood.

From the focus of the blog, however, what Buffet notes is a very real phenomenon. And just as pointed out below, for the many Americans who have no experience with the world as far back as Buffett, the perceptions about history and current affairs, and even the current state of the culture in relation to past cultures, aren't necessarily easily understood or appreciated.

Labels:

Capitalism,

Commentary,

Economics,

Great Depression,

Personalities,

Politics,

You heard it here first

Location:

Omaha, NE, USA

Sunday, February 28, 2016

Lower Class, Middle Class, Upper Class?

Last general election season (as hard as it is to believe that I wrote it that long ago) I took a look at the Middle Class and trends over time in our post Lex Anteinternet: Middle Class. I was looking at this topic again the other day, but for a different reason.

I started that post off with this observation:

As noted, defining who is who is a little difficult, but I'll go, for purposes of this, with what Pew does. For a single person, you enter middle income at $24,173 and you climb into upper income at $74,521. For a married couple (household of two) that changes, however, and the combined incomes need to reach $34,186 to be middle income, and you climb out of that at $102,560. For the archetypal family of four you enter middle income at $48,387 and climb out of it at $145,081.

Those numbers are lower than people suspect, I suspect. And the much discussed figure of $250,000 is actually where the "1%" kicks off.

Now, as it turns out, a very large percentage of middle income Americans pop up into the upper income bracket from time to time, and often in and out of it. I guess that's probably not too surprising. It's more likely, actually, for a person who has an upper middle class occupation, or a bottom upper class occupation, to have a fluctuating income. Some incomes fluctuate wildly from year to year, but they generally fall into the upper class and upper middle class range. So a person can have an upper middle class income one year, and then the next, if it's a good year, will be in the 1% range of the upper class. Pretty darned common.

What is surprising, however, is that a majority, although only barely that, of white Americans are upper income. Additionally, since the 1970s, the elderly, married couples, and blacks improved their economic status more than other groups.

I don't think people realize that at all. So let's look at that again.

Most, although barely most, white Americans are in the upper class. It may be that the "working class whites" are mad and voting for Donald Trump, but most, but barely most, American whites are not in that class. And some who are not, are upper class. Probably quite a few are.

Let's look at the trends even closer.

As noted, blacks' economic status has improved since 1971, in spite of the common assumption to the contrary. Indeed, even a light look at the conditions most blacks lived in at that time, as compared to now, shows how true that is.

Married people did well.

Married people with a college education did particularly well.

Hispanics slipped, however. But more on that in a moment.

The percentage of Americans that are "middle class" is 50% of the overall population now. In 1971 it was 61% of the population. A real drop of over 10%. Scary, maybe.

The percentage of the population that was lower class in 1971 was 16% in 1971 and is 20% now, an increase of 4%, with that percentage climbing up steadily since 1971. The lower middle class, those just above poverty, has been 9% all along, however.

10% of the population was upper middle class in 1971, but now that figure is 12%. The upper class made up 4% of Americans in 1971 and now makes up 9%.

Hmmm.

So, looking at the middle Middle Class, that percentage has retreated as a percent of the overall American population by 11% since 1971. But that loss reflects an increase of 5% in the upper class and an increase of 2% in the upper middle class. So, yes the middle class has retreated, but it's loss of 11% reflects a 7% increase in the wealthy and nearly wealthy. The balance of the loss would reflect an increase in the poor and fighting off poverty.

Taking it further what we are seeing is that the two oldest demographics in the country, loosely defined, whites and blacks, are actually doing very well and doing increasingly well provided that they receive a college education and are married. Amongst the unmarried, men do well, and women do not. More whites are now upper class than any other percentage of the economy, which is a stunning occurrence given that they remain the largest demographic, loosely defined. Having said that, there are certainly poor whites and a large number of middle class whites.

Poverty, however, in increasingly defined in the United States by Hispanic ethnicity and by being an unmarried woman. Being an unmarried female with children is virtually a way to guarantee impoverished status.

Setting aside gender for a moment, even the ethnicity is due some closer analysis, however. Hispanics are probably not "slipping" into poverty but born into it, often in another country. As an ethnicity, they share the same status as Italians and Irish once did, that is they're regarded as a race simply because they're a different culture. They tend, in increasing rates, not to identify themselves as a race at all, and if the statistics were reexamined and they were classified as whites, which might be a better more realistic way to do it, the analysis set out above would instantly change and the majority of white Americans would clearly not be upper class, but actually middle class.

Anyhow, people tend to immigrate as they're poor or oppressed. In the case of Hispanics, it tend to be due to poverty. So, the increase since 1971 readily reflects that in 1971 most Hispanics tended to be native born Americans, but now a large number are immigrants. They'll rise up out of their poverty.

The situation with unmarried women is different, however. In 1971 births out of wedlock were regarded as shameful and the marriage culture in the country was strong in all demographics. Following a series of Supreme Court decisions from the quite liberal Supreme Court of the time state law provisions that reinforced marriage as an institution, if only collaterally, and with the massive change in divorce laws that eliminated the necessity of fault in divorces, the predictions set forth in Humanae vitae by Pope Paul VI came true and continue to amplify throughout the culture and accelerate. The ironic result of that is that the demographic that liberal politicians and social reformers claimed to be helping have been massively hurt. Unmarried women with children and their children have sunk into poverty, while the two oldest demographics in the nation have risen steadily, if married, with one now having more wealthy members than middle class members, albeit only barely.

So then, why don't people recognize this?

That is, why are enraged largely white demographics going for Socialist (of some sort) Bernie Sanderes and Populist but super wealthy Donald Trump? A lot of the cries sound in economics and demographics, but it would appear that those cries are misplaced.

Well, they likely are, quite frankly. But that doesn't mean that they don't reflect something. So let's take a look at how this all plays out in terms of perception.

First, oddly enough, as white Americans have evolved from middle class to upper middle class and upper class, they haven't realized that, by and large. Most white Americans, including the classic family of four, think they're middle class even if they're upper class. A family of four with a breadwinner bringing in $250,000 a year is wealthy, but that same family is unlikely to think of itself that way. Why?

Well, there are a bunch of reasons for that.

For one thing, as whites have expanded into the upper class in large numbers, the ethnic and cultural divide that separated the two classes has decreased enormously.

At one time, to be a member of the upper class had a very distinct class distinction. This is still the case the further up the ladder you get, but not nearly to the extent that was once the case. As university education and shear numbers have pushed the numbers up, and specialization in labor has pushed wages up, the boundaries are now not very clear at all. So plenty of Americans who are middle class live near and associate with Americans who are upper class.

Added to this, the fact that people move in and out of the upper class, and some Americans do that nearly annually, further breaks down that distinction.

And breaking it down further, entire groups including geographic groups have moved classes or up within classes, therefore not seeing that they've moved. I'm certain that a person could find entire classes of kids who went to school in the 1970s and graduate in the 1980s from middle class families that have largely crept into the upper class and upper middle class, more or less together, and therefore don't realize that they've changed classes at all.

And as this has occurred, entire middle class neighborhoods that were at one time in the middle of the middle class are now upper middle class or even mixed upper class, and don't realize it.

Indeed, I saw that emphasized in an analysis trying to prove the opposite, that a lot of the middle class have slipped into the lower middle class or poverty and don't know it. And that may very well be true. That is, demographics that have slipped down remain in the suburbs and still have barbecues in the summer and whatnot, but now are struggling economically. I'm sure that's correct, but likewise I'm sure that the opposite is also true. There are a lot of people having barbecues in "middle class" neighborhoods that do that as its the middle class thing. They would never have evolved socially into upper class, classic, behavior, as they're middle class in culture and don't realize that they're upper class.

Indeed, that emphasizes the cultural aspect of things. Culturally, Americans are middle class. And we always have been. That doesn't really change for most people as they move up in class. And if it does, it takes several generations for that really to take root. And as large numbers have moved up, the cultural distinctions that once existed have often ceased to exist. Indeed, this is comparable to such economic class movements amongst immigrant populations which serves as an example. When the Irish in the US, or the Italians, moved from impoverished to Middle Class, they didn't cease being Irish or Italian, at least not right away.

Another aspect of this is, however, that being upper class, unless you are in the very high incomes, isn't what it once was, as odd as it may seem.

If a huge number of people are in the upper class, for one thing, the question then becomes if it is the "upper class"? Maybe not. Maybe, and significantly, the middle class simply makes more money than it used to. So perhaps the definition of middle class actually reflects what people feel. Statisticians may say that they're upper class, but maybe they really aren't. Maybe the definition needs to be changed.

Indeed, not only have a lot of people moved up out of the middle class into the upper class, but a lot of people in the middle class are no longer near the bottom of it. Lower middle class as a segment of the population has remained stagnant for decades. What is likely missed is that at one time an awfully large percentage of the middle class lived darned near the bottom of the demographic and were in danger of slipping into poverty constantly.

But additionally the economic nature of being upper class, unless you are very high in income, has changed a lot.

Current Americans, including even lower class Americans, have an incredible number of demands on their income. Some of this, indeed a lot of this, is purely voluntary, but even at that, the phenomenon is real.

Housing, a real basic, is much more expensive now than it was in former times. A person can witness this simply by driving through nearly any community that has some age to it. There's nearly always a section of town with small houses, followed by slightly larger houses, all of which are older. The "slightly" larger houses are middle class houses of their eras, and the small ones are often the houses of the poor.

Now, significant in that is that even a lot of the poor in many areas in the country could still purchase a house. It wasn't a great house, but it was a house. This is not very much the case any longer. And middle class homes, as we've explored hear in the past, have grown in size over the years. They've also grown in t he command they put on a person's income.

Indeed, people used to commonly buy a house, once they were married, that they often occupied for life, and they didn't change them often. Now, this tends not to be the case, but what does tend to be the case is that people are willing to go into much greater debt than they once were for a house. If a significant percentage of a person's income is tied up in mortgage payments they don't have that much left, and their purchasing power, therefore, probably doesn't feel very upper class.

This is also true of automobiles for many people. Cars have always been expensive actually, contrary to the myth to the contrary, but people's willingness to buy new cars and lots of cars has changed over the years, although that seems to be changing recently.

Up until relatively recently, say thirty or so years ago, quite a few families had one car. This changed as women in particular entered the workplace in increasing numbers, thereby requiring separate transportation, but that then meant that families owned two cars. Teenagers and young adults still in the household often had a care as well, but that car often tended to be "old", in context. I say in context as cars broke down and became "old" much quicker than they now do, but they accordingly lost their value pretty quickly too.

Now things are much changed.

I still tend to retain vehicles for a really long time myself, as I like what I like and generally don't seek to change things much. But most people do not seem to operate this way, so most working people tend to buy new vehicles fairly rapidly even though the old ones do not really seem to wear out. Teenagers now drive, in many instances, nearly new vehicles, which is a huge change from when I was young. I didn't drive a new vehicle until I was working as a lawyer and I've owned exactly three of them my entire life, even tough I've owned a lot of cars.

And then there's the blizzard of things that people own. Iphones, electronics, this and that. A lot of things don't cost much, but added up they cost a lot.

This is quite a bit different from families in the 1970s which had two cars, one phone, and one television, which was quite common. Indeed, when I was a kid I found families having more than one television to be quite exotic. Having two televisions, or even more, has gone from being a symbol of wealth to routine, but that means that people have routine expenses once associated with the wealthy, to some degree (it also reflects that the price of some things has declined in real terms). It can be taken two ways. On the one hand, wealth has brought all these things into common use, and even the lower class often have some of these items. On the other, if you live in a world where this is the norm, the expenses associated with it are also the norm, and therefore there is not as much money to go around even with a higher income.

Indeed, in a world where the number of cars in a typical household didn't vary much from the middle class to the upper class, and where the difference in economic status could be readily told by the nature of a house and the type of cars, rather than middle class homes now resembling upper class ones, and upper class resembling the 1% houses of old, and everyone having a plethora of items, the situation is quite different.

Take these examples. I knew a couple of truly wealthy people when I was young and I am still aware of where their houses are. Today, I couldn't tell you if those houses are occupied by upper class or upper middle class people (upper class, I suspect). Those same well off people I'm noting interestingly had tended towards buying one, and I do mean one, high end automobile which they then hung on to for the rest of their lives. In two cases, the cars were Mercedes. In the third, the car was an American luxury car, but I've forgotten what it was. Something like a Cadillac.

Now a lot of people have high end cars and they don't keep them. Indeed, I'm really a personal anomaly as my newest vehicle (I'm excluding my wife's vehicle, as she really likes vehicles and has a relatively new (but used when we bought it) vehicle is a 2007 Dodge 3500 diesel truck. I love it. But my daily driver is a 1997 Jeep TJ. I don't intend to replace either of these vehicles ever, although the TJ isn't a good example as Jeepers tend to get a Jeep and customize it, and hang onto it. The truck is a good example, however, as a decade from now I hope I still have it. Indeed, I hope it last me the rest of my life. I don't want another one.

Another reason, I suspect, that this demographic reality is little appreciated is that being "rich", or upper class, is equated in the popular mind with not working, or not working much. The "idle rich" is a common mental image, even though very few in the upper class are in that demographic.

The idle rich, as a class, did once exist, although they were probably never really the majority of the upper class. As a class, they existed in force, if in small numbers, in the late 19th and early 20th Century when the culture of being very well off actually precluded a person from working. This was more so in Europe than in the United States, but even here a really wealthy person, particularly if their wealth was vested rather than earned, tended not to work and culturally was not supposed to, save for a few very limited occupations. That was the basis of the distinction between the Rich and the Neveau Rich. The newly rich had tended to earn that money, and were sort of looked down for that as a result.

Now, that's all passed, and indeed it passed long ago. As more people have moved into the upper class more in the upper class at all levels work, and frankly those in the just upper class, as opposed to the 1% of top incomes, have no choice as a rule. So, upper class often means that a person is in a high paying, but hard working, profession or occupation. Around here, as odd as it may seem to some, there are a lot of experienced oil field hands who are "upper class" by income, or at least there were until the vast number of recent layoffs. These people make a good income, but they have to work, and they have to work hard.

Indeed, even with the traditional occupations that people associate with wealth this is really true. Often that assumption is completely erroneous to start with. Lots of doctors and lawyers, for example, are solidly middle class and not upper class. People's assumptions, expectations, and concepts of themselves are often wildly off the mark.

All of which ties into an election year like the current one. The GOP is seeing sort of a "working class" revolt in its ranks, and the Democrats are as well. But some of those angered voters are doing better than perhaps they realize, in historical terms. And the country overall may be as well. That doesn't mean that economics aren't worth looking at, but when they are looked at, they should be looked at realistically. Turning the country back to a perceived better age or towards a more radical future might be quite a bit off the mark, looking back towards where we've come from.

I started that post off with this observation:

This being an election season, there's a lot of news about the "shrinking middle class". Given the historical focus of this blog, I got to thinking about that and wondered where the "middle class" fit in historic terms in this country, and in the Western World in general. Who were they, and what percentage of the population were they? It turns out to be a much more complicated topic than a person might suppose. That doesn't mean that it isn't shrinking in the US, it is, and that is indeed disturbing. At the same time, the middle class is increasing globally, which is a good thing. Not much noticed in the news, for example, is the fact that for the first time in Mexico's history the middle class is the largest class in that country, having replaced the poor in that category. Nonetheless, even defining what the middle class is is surprisingly tricky. Indeed, defining the poor is tricky too, or the wealthy, with definitions varying depending upon where you are in the world. That later fact probably explains much of the difficult Western nations have grasping the concerns of poorer ones, fwiw.In looking at this topic again, and again struggling with who the middle class is, I ran across some interesting information that perhaps should somewhat inform how we look at this. It's interesting. Particularly in this election year when class distinctions seem to be running rampant through some campaigns, namely the Sanders and Trump campaigns, with it being widely assumed that the (white) "working class" is taking a huge pounding in our economy. It's worth asking, what do the statistics show?

As noted, defining who is who is a little difficult, but I'll go, for purposes of this, with what Pew does. For a single person, you enter middle income at $24,173 and you climb into upper income at $74,521. For a married couple (household of two) that changes, however, and the combined incomes need to reach $34,186 to be middle income, and you climb out of that at $102,560. For the archetypal family of four you enter middle income at $48,387 and climb out of it at $145,081.

Those numbers are lower than people suspect, I suspect. And the much discussed figure of $250,000 is actually where the "1%" kicks off.

Now, as it turns out, a very large percentage of middle income Americans pop up into the upper income bracket from time to time, and often in and out of it. I guess that's probably not too surprising. It's more likely, actually, for a person who has an upper middle class occupation, or a bottom upper class occupation, to have a fluctuating income. Some incomes fluctuate wildly from year to year, but they generally fall into the upper class and upper middle class range. So a person can have an upper middle class income one year, and then the next, if it's a good year, will be in the 1% range of the upper class. Pretty darned common.

What is surprising, however, is that a majority, although only barely that, of white Americans are upper income. Additionally, since the 1970s, the elderly, married couples, and blacks improved their economic status more than other groups.

I don't think people realize that at all. So let's look at that again.

Most, although barely most, white Americans are in the upper class. It may be that the "working class whites" are mad and voting for Donald Trump, but most, but barely most, American whites are not in that class. And some who are not, are upper class. Probably quite a few are.

Let's look at the trends even closer.

As noted, blacks' economic status has improved since 1971, in spite of the common assumption to the contrary. Indeed, even a light look at the conditions most blacks lived in at that time, as compared to now, shows how true that is.

Married people did well.

Married people with a college education did particularly well.

Hispanics slipped, however. But more on that in a moment.

The percentage of Americans that are "middle class" is 50% of the overall population now. In 1971 it was 61% of the population. A real drop of over 10%. Scary, maybe.

The percentage of the population that was lower class in 1971 was 16% in 1971 and is 20% now, an increase of 4%, with that percentage climbing up steadily since 1971. The lower middle class, those just above poverty, has been 9% all along, however.

10% of the population was upper middle class in 1971, but now that figure is 12%. The upper class made up 4% of Americans in 1971 and now makes up 9%.

Hmmm.

So, looking at the middle Middle Class, that percentage has retreated as a percent of the overall American population by 11% since 1971. But that loss reflects an increase of 5% in the upper class and an increase of 2% in the upper middle class. So, yes the middle class has retreated, but it's loss of 11% reflects a 7% increase in the wealthy and nearly wealthy. The balance of the loss would reflect an increase in the poor and fighting off poverty.

Taking it further what we are seeing is that the two oldest demographics in the country, loosely defined, whites and blacks, are actually doing very well and doing increasingly well provided that they receive a college education and are married. Amongst the unmarried, men do well, and women do not. More whites are now upper class than any other percentage of the economy, which is a stunning occurrence given that they remain the largest demographic, loosely defined. Having said that, there are certainly poor whites and a large number of middle class whites.

Poverty, however, in increasingly defined in the United States by Hispanic ethnicity and by being an unmarried woman. Being an unmarried female with children is virtually a way to guarantee impoverished status.

Setting aside gender for a moment, even the ethnicity is due some closer analysis, however. Hispanics are probably not "slipping" into poverty but born into it, often in another country. As an ethnicity, they share the same status as Italians and Irish once did, that is they're regarded as a race simply because they're a different culture. They tend, in increasing rates, not to identify themselves as a race at all, and if the statistics were reexamined and they were classified as whites, which might be a better more realistic way to do it, the analysis set out above would instantly change and the majority of white Americans would clearly not be upper class, but actually middle class.

Anyhow, people tend to immigrate as they're poor or oppressed. In the case of Hispanics, it tend to be due to poverty. So, the increase since 1971 readily reflects that in 1971 most Hispanics tended to be native born Americans, but now a large number are immigrants. They'll rise up out of their poverty.

The situation with unmarried women is different, however. In 1971 births out of wedlock were regarded as shameful and the marriage culture in the country was strong in all demographics. Following a series of Supreme Court decisions from the quite liberal Supreme Court of the time state law provisions that reinforced marriage as an institution, if only collaterally, and with the massive change in divorce laws that eliminated the necessity of fault in divorces, the predictions set forth in Humanae vitae by Pope Paul VI came true and continue to amplify throughout the culture and accelerate. The ironic result of that is that the demographic that liberal politicians and social reformers claimed to be helping have been massively hurt. Unmarried women with children and their children have sunk into poverty, while the two oldest demographics in the nation have risen steadily, if married, with one now having more wealthy members than middle class members, albeit only barely.

So then, why don't people recognize this?

That is, why are enraged largely white demographics going for Socialist (of some sort) Bernie Sanderes and Populist but super wealthy Donald Trump? A lot of the cries sound in economics and demographics, but it would appear that those cries are misplaced.

Well, they likely are, quite frankly. But that doesn't mean that they don't reflect something. So let's take a look at how this all plays out in terms of perception.

First, oddly enough, as white Americans have evolved from middle class to upper middle class and upper class, they haven't realized that, by and large. Most white Americans, including the classic family of four, think they're middle class even if they're upper class. A family of four with a breadwinner bringing in $250,000 a year is wealthy, but that same family is unlikely to think of itself that way. Why?

Well, there are a bunch of reasons for that.

For one thing, as whites have expanded into the upper class in large numbers, the ethnic and cultural divide that separated the two classes has decreased enormously.

At one time, to be a member of the upper class had a very distinct class distinction. This is still the case the further up the ladder you get, but not nearly to the extent that was once the case. As university education and shear numbers have pushed the numbers up, and specialization in labor has pushed wages up, the boundaries are now not very clear at all. So plenty of Americans who are middle class live near and associate with Americans who are upper class.

Added to this, the fact that people move in and out of the upper class, and some Americans do that nearly annually, further breaks down that distinction.

And breaking it down further, entire groups including geographic groups have moved classes or up within classes, therefore not seeing that they've moved. I'm certain that a person could find entire classes of kids who went to school in the 1970s and graduate in the 1980s from middle class families that have largely crept into the upper class and upper middle class, more or less together, and therefore don't realize that they've changed classes at all.

And as this has occurred, entire middle class neighborhoods that were at one time in the middle of the middle class are now upper middle class or even mixed upper class, and don't realize it.

Indeed, I saw that emphasized in an analysis trying to prove the opposite, that a lot of the middle class have slipped into the lower middle class or poverty and don't know it. And that may very well be true. That is, demographics that have slipped down remain in the suburbs and still have barbecues in the summer and whatnot, but now are struggling economically. I'm sure that's correct, but likewise I'm sure that the opposite is also true. There are a lot of people having barbecues in "middle class" neighborhoods that do that as its the middle class thing. They would never have evolved socially into upper class, classic, behavior, as they're middle class in culture and don't realize that they're upper class.

Indeed, that emphasizes the cultural aspect of things. Culturally, Americans are middle class. And we always have been. That doesn't really change for most people as they move up in class. And if it does, it takes several generations for that really to take root. And as large numbers have moved up, the cultural distinctions that once existed have often ceased to exist. Indeed, this is comparable to such economic class movements amongst immigrant populations which serves as an example. When the Irish in the US, or the Italians, moved from impoverished to Middle Class, they didn't cease being Irish or Italian, at least not right away.

Another aspect of this is, however, that being upper class, unless you are in the very high incomes, isn't what it once was, as odd as it may seem.

If a huge number of people are in the upper class, for one thing, the question then becomes if it is the "upper class"? Maybe not. Maybe, and significantly, the middle class simply makes more money than it used to. So perhaps the definition of middle class actually reflects what people feel. Statisticians may say that they're upper class, but maybe they really aren't. Maybe the definition needs to be changed.

Indeed, not only have a lot of people moved up out of the middle class into the upper class, but a lot of people in the middle class are no longer near the bottom of it. Lower middle class as a segment of the population has remained stagnant for decades. What is likely missed is that at one time an awfully large percentage of the middle class lived darned near the bottom of the demographic and were in danger of slipping into poverty constantly.

But additionally the economic nature of being upper class, unless you are very high in income, has changed a lot.

Current Americans, including even lower class Americans, have an incredible number of demands on their income. Some of this, indeed a lot of this, is purely voluntary, but even at that, the phenomenon is real.

Housing, a real basic, is much more expensive now than it was in former times. A person can witness this simply by driving through nearly any community that has some age to it. There's nearly always a section of town with small houses, followed by slightly larger houses, all of which are older. The "slightly" larger houses are middle class houses of their eras, and the small ones are often the houses of the poor.

Now, significant in that is that even a lot of the poor in many areas in the country could still purchase a house. It wasn't a great house, but it was a house. This is not very much the case any longer. And middle class homes, as we've explored hear in the past, have grown in size over the years. They've also grown in t he command they put on a person's income.

Indeed, people used to commonly buy a house, once they were married, that they often occupied for life, and they didn't change them often. Now, this tends not to be the case, but what does tend to be the case is that people are willing to go into much greater debt than they once were for a house. If a significant percentage of a person's income is tied up in mortgage payments they don't have that much left, and their purchasing power, therefore, probably doesn't feel very upper class.

This is also true of automobiles for many people. Cars have always been expensive actually, contrary to the myth to the contrary, but people's willingness to buy new cars and lots of cars has changed over the years, although that seems to be changing recently.

Up until relatively recently, say thirty or so years ago, quite a few families had one car. This changed as women in particular entered the workplace in increasing numbers, thereby requiring separate transportation, but that then meant that families owned two cars. Teenagers and young adults still in the household often had a care as well, but that car often tended to be "old", in context. I say in context as cars broke down and became "old" much quicker than they now do, but they accordingly lost their value pretty quickly too.

Now things are much changed.

I still tend to retain vehicles for a really long time myself, as I like what I like and generally don't seek to change things much. But most people do not seem to operate this way, so most working people tend to buy new vehicles fairly rapidly even though the old ones do not really seem to wear out. Teenagers now drive, in many instances, nearly new vehicles, which is a huge change from when I was young. I didn't drive a new vehicle until I was working as a lawyer and I've owned exactly three of them my entire life, even tough I've owned a lot of cars.

And then there's the blizzard of things that people own. Iphones, electronics, this and that. A lot of things don't cost much, but added up they cost a lot.

This is quite a bit different from families in the 1970s which had two cars, one phone, and one television, which was quite common. Indeed, when I was a kid I found families having more than one television to be quite exotic. Having two televisions, or even more, has gone from being a symbol of wealth to routine, but that means that people have routine expenses once associated with the wealthy, to some degree (it also reflects that the price of some things has declined in real terms). It can be taken two ways. On the one hand, wealth has brought all these things into common use, and even the lower class often have some of these items. On the other, if you live in a world where this is the norm, the expenses associated with it are also the norm, and therefore there is not as much money to go around even with a higher income.

Indeed, in a world where the number of cars in a typical household didn't vary much from the middle class to the upper class, and where the difference in economic status could be readily told by the nature of a house and the type of cars, rather than middle class homes now resembling upper class ones, and upper class resembling the 1% houses of old, and everyone having a plethora of items, the situation is quite different.

Take these examples. I knew a couple of truly wealthy people when I was young and I am still aware of where their houses are. Today, I couldn't tell you if those houses are occupied by upper class or upper middle class people (upper class, I suspect). Those same well off people I'm noting interestingly had tended towards buying one, and I do mean one, high end automobile which they then hung on to for the rest of their lives. In two cases, the cars were Mercedes. In the third, the car was an American luxury car, but I've forgotten what it was. Something like a Cadillac.

Now a lot of people have high end cars and they don't keep them. Indeed, I'm really a personal anomaly as my newest vehicle (I'm excluding my wife's vehicle, as she really likes vehicles and has a relatively new (but used when we bought it) vehicle is a 2007 Dodge 3500 diesel truck. I love it. But my daily driver is a 1997 Jeep TJ. I don't intend to replace either of these vehicles ever, although the TJ isn't a good example as Jeepers tend to get a Jeep and customize it, and hang onto it. The truck is a good example, however, as a decade from now I hope I still have it. Indeed, I hope it last me the rest of my life. I don't want another one.

Another reason, I suspect, that this demographic reality is little appreciated is that being "rich", or upper class, is equated in the popular mind with not working, or not working much. The "idle rich" is a common mental image, even though very few in the upper class are in that demographic.

The idle rich, as a class, did once exist, although they were probably never really the majority of the upper class. As a class, they existed in force, if in small numbers, in the late 19th and early 20th Century when the culture of being very well off actually precluded a person from working. This was more so in Europe than in the United States, but even here a really wealthy person, particularly if their wealth was vested rather than earned, tended not to work and culturally was not supposed to, save for a few very limited occupations. That was the basis of the distinction between the Rich and the Neveau Rich. The newly rich had tended to earn that money, and were sort of looked down for that as a result.

Now, that's all passed, and indeed it passed long ago. As more people have moved into the upper class more in the upper class at all levels work, and frankly those in the just upper class, as opposed to the 1% of top incomes, have no choice as a rule. So, upper class often means that a person is in a high paying, but hard working, profession or occupation. Around here, as odd as it may seem to some, there are a lot of experienced oil field hands who are "upper class" by income, or at least there were until the vast number of recent layoffs. These people make a good income, but they have to work, and they have to work hard.

Indeed, even with the traditional occupations that people associate with wealth this is really true. Often that assumption is completely erroneous to start with. Lots of doctors and lawyers, for example, are solidly middle class and not upper class. People's assumptions, expectations, and concepts of themselves are often wildly off the mark.

All of which ties into an election year like the current one. The GOP is seeing sort of a "working class" revolt in its ranks, and the Democrats are as well. But some of those angered voters are doing better than perhaps they realize, in historical terms. And the country overall may be as well. That doesn't mean that economics aren't worth looking at, but when they are looked at, they should be looked at realistically. Turning the country back to a perceived better age or towards a more radical future might be quite a bit off the mark, looking back towards where we've come from.

Labels:

Capitalism,

Economics,

Ethnicities,

Politics,

Socialism,

trends

Sunday Morning Scene: Churches of the West: Elk Mountain, Wyoming

Churches of the West: Elk Mountain, Wyoming:

I don't know, or no longer know, the denomination of this church in the rural town of Elk Mountain, Wyoming. This is, in part, because this photo was taken in 1986.

I don't know, or no longer know, the denomination of this church in the rural town of Elk Mountain, Wyoming. This is, in part, because this photo was taken in 1986.

Labels:

Architecture,

Blog Mirror,

Christianity,

Churches,

Churches of the West,

Elk Mountain Wyoming,

Protestant,

religion,

Sunday Morning Scene

Location:

Elk Mountain, WY 82324, USA

Thursday, February 25, 2016

Ancestry.com: 11 Skills Your Great-Grandparents Had That You Don’t

Here's another entry from Ancestry.com with some interesting items:

11 Skills Your Great-Grandparents Had That You Don’t

This entry does say that "most of us don't" have these skills, which would acknowledge that some of us do. It's interesting to take a look at these to see how accurate this assessment is. The last one of these we posted from Ancestry.com was, in fact, pretty accurate. So much so that we'll be following up some of the items listed there.Our parents and grandparents may shake their heads every time we grab our smart phones to get turn-by-turn directions or calculate the tip. But when it comes to life skills, our great-grandparents have us all beat. Here are some skills our great-grandparents had 90 years ago that most of us don’t.

Okay, here's their list:

This is an interesting item, and one we haven't covered very much, although I think we have slightly, perhaps in one of the older threads on marriage. Here's what Ancestry.com noted:

While your parents and grandparents didn’t have the option to ask someone out on a date via text message, it’s highly likely that your great-grandparents didn’t have the option of dating at all. Until well into the 1920s, modern dating didn’t really exist. A gentleman would court a young lady by asking her or her parents for permission to call on the family. The potential couple would have a formal visit — with at least one parent chaperone present — and the man would leave a calling card. If the parents and young lady were impressed, he’d be invited back again and that would be the start of their romance.

2. Hunting, Fishing, and Foraging

I have posted on this quite a bit.

The way that Ancestry.com stated it is a bit different than I expected, however. They stated:

Even city dwellers in your great-grandparents’ generation had experience hunting, fishing, and foraging for food. If your great-grandparents never lived in a rural area or lived off the land, their parents probably did. Being able to kill, catch, or find your own food was considered an essential life skill no matter where one lived, especially during the Great Depression.Ancestry.com may have pushed their point a bit, but perhaps not. I may have to follow up on this. Having said that, hunting and fishing remain very popular, and in fact increasingly popular, activities in the United States today.

And this is one skill that I do indeed have, and probably at least to the same extent my grandparents did.

3. Butchering

This is one that surprised me as well. Here's what Ancestry.com

In this age of the boneless, skinless chicken breast, it’s unusual to have to chop up a whole chicken at home, let alone a whole cow. Despite the availability of professionally butchered and packaged meats, knowing how to cut up a side of beef or butcher a rabbit from her husband’s hunting trip was an ordinary part of a housewife’s skill set in the early 20th century. This didn’t leave the men off the hook, though. After all, they were most likely the ones who would field dress any animals they killed.I think that Ancestry.com may have pushed their point here, quite frankly. But there is something to the point that there used to be more cutting of mean even from the grocery store than there is now. My father was very good at this, and at butchering game as well, which is in fact a skill he learned from his father, who had owned a packing house.

But this is also one that I have done and can do.

4. Bartering

Hmmm. . . I'm not sure how much bartering has gone on in North America in the period we're discussing. Some I'm sure. Some isn't really bartering so much as a gift on the part of people who've received one, which is worth noting.

5. Haggling

This one I doubt as well. At one time perhaps this was common, but it would be further back than our grandparents generation.

6. Darning and mending

This one I accept. As a kid, my mother often repaired my clothes and her own clothes as well. People seemingly do little of that now.

7. Corresponding by mail

We've addressed this, including just the other day, and this is certainly true.

My mother kept up a vigorous correspondence with her siblings. And one of my cousins has posted some of my grandparents', on my mother's side, correspondence and it is clear that they wrote to each other a great deal.

8. Making Lace

This is no doubt true. Probably hardly any younger woman knows how to do this now, and my guess is that the living women who do are quite elderly.

9. Lighting a Fire Without Matches

No doubt true.

10. Diapering With Cloth

And also no doubt true.

Some environmentally conscious people today do use cloth diapers, but they are few and far between. Frankly, this would be a huge chore, due to the laundry it entails.

When I was a baby, cloth diapers were the only kind that existed. I don't even know where a person would get them now.

11. Writing With a Fountain Pen

Very true, and one I've posted on here before:

Pens and Pencils

I just learned the other day that ballpoint pens came about in the 1940s. Apparently, in the WWII time frame, they remained largely unreliable.

Waterman fountain pen advertisement, claiming the pen to be the "the arm of peace" in French.I don't know why that surprised me, but it did. Pens, in the 40s, and the 50s, largely remained fountain pens.

Frankly, even the Bic ballpoint pens I used through most of junior high and high school were less than reliable. The ink dried up, or it separated in the plastic tube holding it. Sometimes they leaked and the ink came out everywhere. But they were easier to use than fountain pens. With fountain pens I was always like Charlie Brown in the cartoons, with ink going absolutely everywhere, or at least all over my hands.

Wednesday, February 24, 2016

"I'll go to Canada". No, Yankee, you will not.

One of the most common refrains I hear from Americans of all political stripes, concerning an election outcome they don't like, is "I'll go to Canada".

Canadian Parliament Building. The parliament hasn't voted to open the doors to unhappy Americans over losing an election.

Canada is a sovereign nation with its own immigration policies and they don't want you. It's rude and presumptuous of you to assume you can just move in.

Why would they want you?

"Disgruntled about my country's politics" is not a category for immigration into any country, let alone to our neighbor the north which has a bit of a chip on its shoulder about the common American assumption that we somehow own Canada, or that Canada is "United States Lite" or something.

You aren't moving there. They don't want you. Unhappy with an election outcome just shows you are disgruntled, not that you'd make a good Canadian. Besides, you just can't "move there". They have to accept you as a resident, and there are a lot of other, non disgruntled people, from all over the world trying to do the same thing.

Not only that, but frankly, most Americans unhappy with our election outcomes would be really unhappy with Canadian ones. Think that Bernie Sanders is too darned far to the left? Have you heard of Justin Trudeau? Upset about Donald Trump and think the country's gone to far to the populist right? Are you aware that Canada actually does impose speech restrictions on some controversial matters, having no Constitutional prohibitions to the contrary. You, disgruntled American, aren't going to be happier there. You'll just be annoying Canadians.

Labels:

Canada,

Politics,

Random snippets,

Satire

Location:

Canada

Tuesday, February 23, 2016

Ancestry.com: 9 Reasons Your Great-Great-Grandparents Were More Awesome Than You

An interesting item from Ancestry.com:

1. They could probably ride and care for a horse.

Well, maybe not so much.

I've addressed equine transportation quite a few times on this blog. The definative one, if there is one, is likely here:

As explored here, and elsewhere, most people actually didn't ride that much. Horses are expensive and require daily upkeep of some sort.

Now, for rural people, of which there were a great deal more then, than as opposed to now, as a percentage of the population, knowledge of equine transportation was certainly the rule.

So here, Ancestry.com hits and misses.

Another thing I'll have to cover.

Here's the actual entry from Ancestry.com:

This is an interesting one. Here's the actual entry:

This is one that I have covered here quite a bit, in numerous different ways. An older short one (which is hardly the only time I've covered it) is here:

Of course, a lot of our ancestors were probably working as domestic help as well, which is, and was, a pretty hard job.

But, once again, something to cover.

That can be a burden as well as a benefit, quite frankly. That is, we shouldn't always assume that people enjoy these changes. Some do, some don't, but its mixed for most. Often its put just the way it is here, but perhaps we should be a bit more introspective on this one.

Well, Ancestry.com. Nice job all and all. And also, thanks for giving me ideas for some topics I need to explore.

So how's it hold up? Here, without the accompanying text, are the nine reasons?As 21st-century adults, it’s hard to fathom the kind of lives our great-great-grandparents led. While there were many difficulties they had to contend with, there were also many advantages to a pre-digital life in the 1870s and 1880s. . .

1. They could probably ride and care for a horse.Is Ancestry.com right? Well, not too surprisingly, given that I find a lot of this stuff interesting, I've already addressed a bunch of these right here. And, given that, I'd have to say that Ancestry.com doesn't do too bad, but they aren't 100% on the mark either. Let's look at each one a bit more carefully.

.

2. They wrote and received letters regularly.

3. They could get by without electricity.

4. They could make their own household goods.

5. They knew how to behave in different social situations.

6. They could get a good job without a lot of education.

7. They could get cheap household help.

8. They got to witness the earliest years of some of the most fascinating things in modern life.

9. They didn’t have to explain their facial hair to anyone.

1. They could probably ride and care for a horse.

Well, maybe not so much.

I've addressed equine transportation quite a few times on this blog. The definative one, if there is one, is likely here:

Having said that, this one is pretty relevant too:

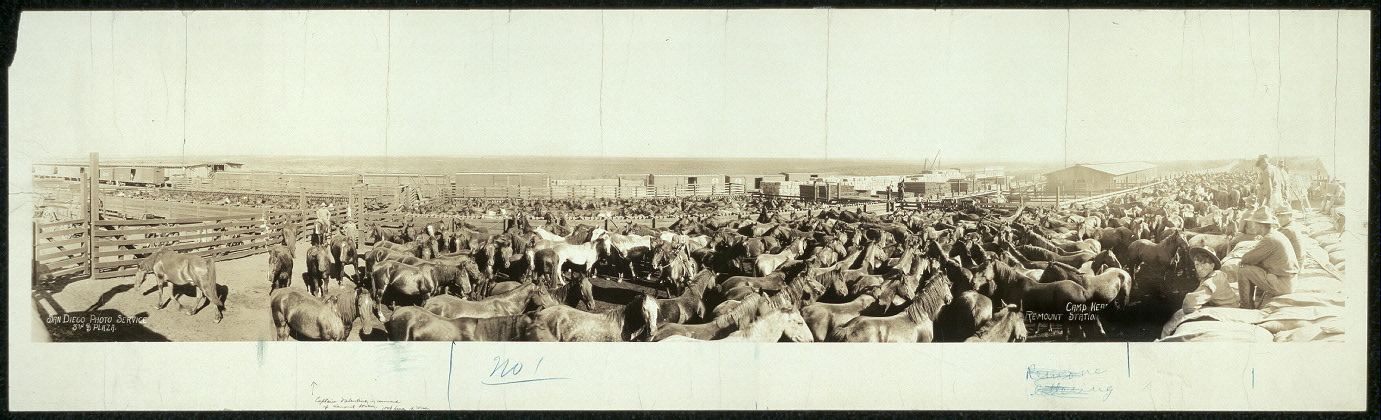

Remounts. World War One.I've been doing a series of posts here recently on transportation. I started out with the default means of transportation, walking, and then recently I did one on bicycles, the device that first introduced practical daily mechanical transportation to most people, most places, in the western world, and which continues to be the default means of daily transportation for a lot of people around the globe. Here I turn to nearly the oldest means of alternative ground transportation (accepting that floating transportation was the second means for humans to get around, following walking), that being animal transportation. And when we discuss animal transportation, we mean for the most part equine transportation, at least in the context discussed here..

Walking

For the overwhelming majority of human history, if a person wanted to get somewhere, anywhere, they got there one of two ways.

They walked, or they ran.

That's it.

Businessmen, Washington D. C., 1940s. Walking.Alternative modes of transportation didn't even exist for much of human history. The boat was almost certainly the very first one to occur to anyone. Or rather, the canoe. People traveled by canoe before they traveled by any other means other than walking. . .

As explored here, and elsewhere, most people actually didn't ride that much. Horses are expensive and require daily upkeep of some sort.

Now, for rural people, of which there were a great deal more then, than as opposed to now, as a percentage of the population, knowledge of equine transportation was certainly the rule.

So here, Ancestry.com hits and misses.

2. They wrote and received letters regularly.Ancestry.com is right on the mark here, that's for sure. I've touched on this quite a bit too, including one fairly recent entry. So Ancestry.com gets high marks here, and indeed, this topic is well worth writing about here again, and I likely shall.

3. They could get by without electricity.Very true. And a topic I haven't directly covered. I'll have to add this one to the hopper.

4. They could make their own household goods.Also at least somewhat true, depending upon the era and what we're addressing. Actually, for most of us, it'd be more true of our great grandparents, or perhaps our great great grandparents, but even our immediate parents were generally handier than most people are now.

Another thing I'll have to cover.

Here's the actual entry from Ancestry.com:

Great-great-grandma probably sewed all her own household linens, complete with fancy embroidery, tatting, or other decorative embellishments. She could probably knit, crochet, or hook rugs. While some of these skills are becoming popular again, the ready availability of manufactured textiles has made most of them hobbies rather than essential life skills.Cudos to Ancestry.com again. Another topic right on point for this blog that I've failed to cover.

5. They knew how to behave in different social situations.This is one that wouldn't have occurred to me, but I think there's some truth to it. Another one that I need to cover here.

6. They could get a good job without a lot of education.

This is an interesting one. Here's the actual entry:

The movement for compulsory secondary education didn’t begin in the U.S. until the 1890s, so many adults in the 1870s and ’80s had only an elementary education. Still, they were able to find good-paying jobs in manufacturing — steel, meatpacking, and other major industries. Of course, these jobs didn’t pay nearly as much as most skilled labor jobs, which required years of apprenticeship prior to employment. A college education was mostly for the elite. Student loan debt was unheard of.Very true again.

This is one that I have covered here quite a bit, in numerous different ways. An older short one (which is hardly the only time I've covered it) is here:

I've covered daily living and the burden or household chores a lot, and in depth, here. But hiring domestic help I haven't covered.Engineering Building, University of Wyoming, 1950s.

First of all, let me start off by noting that I'm not posting this as a screed advocating dropping out of school, quite the opposite.

Anyhow, this is my second social history post of the day. The first one, posted just below, concerns weddings, this one concerns education.

Some friends and I were observing how the value of degrees has changed over the past couple of decades. The change is really quite remarkable.

7. They could get cheap household help.

Of course, a lot of our ancestors were probably working as domestic help as well, which is, and was, a pretty hard job.

But, once again, something to cover.

8. They got to witness the earliest years of some of the most fascinating things in modern life.I think I've covered this, but as a matter of prospective. That is, we think we live in a time with a blistering pace of change, but compared to earlier eras, but not all that long ago, not so much.

That can be a burden as well as a benefit, quite frankly. That is, we shouldn't always assume that people enjoy these changes. Some do, some don't, but its mixed for most. Often its put just the way it is here, but perhaps we should be a bit more introspective on this one.

9. They didn’t have to explain their facial hair to anyone.True. And another one I've covered a couple of times.

Well, Ancestry.com. Nice job all and all. And also, thanks for giving me ideas for some topics I need to explore.

Monday, February 22, 2016

Alcohol and the law.

Should a sign like this come with your card of admission to the bar?

But now, for the first time in decades, a team of researchers has verified and quantified the problem in a newly published study that shows that 21 percent of attorneys qualify as problem drinkers, 28 percent struggle with depression and 19 percent have anxiety.Wow, that's a really high percentage. I wouldn't have guessed it was anywhere near that amount. I frankly doubted that but when I went to post this item, I found this one from a couple of years ago:

Hmm, the converse there isn't very comforting.Studies conducted in numerous jurisdictions have pegged the rate of alcoholism in the legal profession at between 15% and 24%. Roughly 1 in 5 lawyers is addicted to alcohol. Of course, the converse is true,namely that the majority have no problem in consuming alcohol.

Indeed, given the way statistics work, if 15% to 24% of lawyers are alcoholics, there must be a certain percentage above that who have some sort of problem with alcohol, assuming that a person can have a problem with alcohol and not be an alcoholic. That does bring up the oddity that what constitutes being an alcoholic is, oddly, not universally defined. You would think it would be, but it isn't. Daily drinking doesn't equate with being an alcoholic, contrary to what some teetotalers feel, although in recent years some former drinking cultures have sort of headed that way, oddly enough. Generally a male can drink up to two "drinks" per day and be regarded as a moderate drinking, but above that puts you in some other category. The amount is less for women. Having said that, if addiction is considered, that's a different equation I guess (I"m not an expert on this, rather obviously).

Indeed, it's been interesting to note that columnist Froma Harrop has been sort of at war with the trend in some quarters in pretty strongly advocating her view that a drink a day or two for men isn't something that people ought to be up in arms about. That takes some guts on her part, as generally even people who drink a couple of drinks per day are going to be reluctant, in this environment, to admit it. Harrop went one step further the other day and wrote a column arguing that 18 year olds should be allowed to drink, on the logical basis that if you are old enough to serve in the military, and to vote, you should be old enough to drink. That's not going to happen here in the US, however, if for no other reason that this is one of those areas where an old Puritan ethic survives, even tough the Puritans were not teetotalers.

So, getting back on point, if 15% to 24%, or in the other calculation 21%, of lawyers are alcoholics, it must also mean that at least a few more percent are somewhere on the scale of maybe having a problem or verging on one. And there'd be a few who must have problems with other substances, although a lot of those would be individuals who also have a problem with alcohol. Having said that, about a year or more ago I worked on a matter where one lawyer frankly told me about another former lawyer in his firm that that the guy had a problem with marijuana, which is fully illegal here. Of course, there was a lot of bad blood going on there, so I don't have a clue if that was really true. I know that our bar is pretty darned aggressive about addressing lawyer misconduct, so I wonder.

Indeed, the ABA, in one of the periodic emails it sends out, reports from some ABA convention that:

On Wednesday, Hazelden and the ABA Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs released the study that showed 21 percent of licensed, employed attorneys qualify as problem drinkers, 28 percent struggle with some level of depression and 19 percent demonstrate symptoms of anxiety. It found that younger attorneys in the first 10 years of practice exhibit the highest incidence of these problems. The findings were posted online this week in the Journal of Addiction Medicine, with the print edition available in mid-February.So it was at 21%, but went on to note:

When focusing on three of the 10 questions that measured only volume and frequency of drinking, the authors arrived at the conclusion that more than 1 in 3 practicing attorneys are problem drinkers even though the attorneys themselves might not characterize themselves as that.So that would be 33%. That's a stunning figure.

Old Parr. Apparently this Scotch whiskey was named after the oldest man in England, and is still distilled, although its no longer sold in the UK but only in export markets. I don't know much about Parr, other than that he lived on a spartan diet, but which included a small drink of something each day, and lived to a reputed 152 years old, which is way old, if true. Ironically, his death was precipitated by rich eating when he became famous in his advanced old age.

Anyhow, if this many lawyers have a problem, a person would still have to ask why this is the case. One Blawg, Above the Law commented on it as follows:

Earlier this week, a tipster sent us a link to a Greedy Associates post entitled “Why Do Lawyers Drink So Much?” My initial thought was “Ugh.” Honestly, somebody writes that article every three months, and every six months we have to write another version of the same story.

The reasons given for lawyer alcoholism are always the same. “Lawyers are only alcoholic because they’re super TYPE A badasses.” “Lawyers hate their jobs and drink to forget.” “It’s not the law that makes people alcoholics, it’s alcoholics who choose the law!”

I was going to ignore this latest Drunks and the Law story, but then the scotch in my coffee kicked in and I thought, “Hey, isn’t it just that lawyers drink because they can?”

Think about it: being a lawyer is a great job to have if you want to drink as much as possible while also having a job…

Well, presumably this was written with tongue in cheek. Having said that, now I really wonder how many lawyers are functioning alcoholics? I frankly am still stunned that the figure for the percentage who are alcoholics is up over 20%. I don't see a lot of lawyers boozing it up, so if people are, they're doing it, I guess, in the privacy of their own homes or something.

Here’s my premise: being a “functional alcoholic” is the best kind of function and the best kind of alcoholic. Functional alcoholics get to do fun things like hang out with their friends, get hammered and hook-up with random people, then claim they “don’t remember” it in the morning. But they also get to hold onto their jobs, have relationships, and, of course, they don’t have to go to meetings.

Still, what's that say about the law and lawyers? Whatever it is, it isn't good.

I recently sat in a computer CLE put on by the ABA regarding Introverts in the Law. I'm fairly introverted myself, so I thought it might be interesting to hear what the had to say. One thing I did think was really interesting is that, contrary to what people suppose, Introverts aren't necessarily shy nor non gregarious. They can and do interact with people, it's just that they need down time and they sort of retreat into themselves at some point. Often, the people speaking claimed, others are surprised to find out that somebody else is an introvert. I'll be that's really true. That's probably also why the families of introverted lawyers, supposedly up over 60% of the profession, are probably routinely frustrated with the spouses, who are busy and being engaged and engaging all day, only to come home and say "no. . . I don't want to go to a Super Bowl party. . . can't you watch it here while I work on the car?"

That's a sudden shift in this conversation, but I think the Above the Law item on "Type A" personalities is wrong, as I suspect a lot of lawyers aren't Type A, whatever Type A is, but something a lot more complex. And I'm wondering if the severely introverted, and those folks do exist, are shutting their minds down that way. Very bad, if true.

What that suggests is a couple of things, I suppose. For one thing, if a person isn't they type of person who can be around others for at least 8 to 10 hours a day, and is so introverted that they hate to call that witness or opposing lawyer, maybe you ought to think twice about this as a career. And it would seem very clear to me if you have a problem with alcohol before you are ready to take the bar, you better avoid this career as you may be setting yourself up. And I guess I now know why so many state bars have a substance abuse program, which was a bit of a mystery to me before.

I still wonder, however. 21%? That seems awfully high.

Are a lot of lawyers hitting the bottle? Seems so. Is ten years old a long time for Scotch? I have no idea, as Scotch tastes like paint thinner and I can't imagine why anyone drinks it.

Labels:

Alcohol,

Career advice,

Commentary,

Daily Living,

Medicine,

Monday at the bar,

The Practice of Law

Sunday, February 21, 2016

Limiting Supreme Court terms

An interesting proposal is being floated to limit Supreme Court terms to 18 years, with those terms being staggered so that one comes up every two years.

As much as I feel that thirty year veteran Justice, the late Antonin Scalia, was a great justice, this is a good idea. I wish it would get some traction, even though I know that it is unlikely to.

The fact of the matter is that any one U.S. Supreme Court justice has an inordinate amount of power and, by extension, it causes the dead hand of the President who nominated them to live on well after it should not. Scalia was nominated by the late President Reagan. Long serving and highly infirm Justice Douglas, served for forty years and had been appointed by Franklin Roosevelt, only to go out under Gerald Ford.

I'd also modify the proposal, were it me, to require a retirement age of age 70. I know that's an unpopular idea and it would mean that no justice over age 52 could be appointed, but so be it. Douglas is a good example of what can happen when very old justices continue to serve, but he's not the only one. The current system simply requires too much gambling.

Sunday Morning Scene: Churches of the West: St. Luke's Episcopal Church, Buffalo Wyoming

Churches of the West: St. Luke's Episcopal Church, Buffalo Wyoming:

This is St. Luke's Episcopal Church in Buffalo Wyoming. It was built in 1889. Oddly enough, it's one of two St. Luke's in Buffalo, the other being a Lutheran Church across town.

This is St. Luke's Episcopal Church in Buffalo Wyoming. It was built in 1889. Oddly enough, it's one of two St. Luke's in Buffalo, the other being a Lutheran Church across town.

This is St. Luke's Episcopal Church in Buffalo Wyoming. It was built in 1889. Oddly enough, it's one of two St. Luke's in Buffalo, the other being a Lutheran Church across town.

This is St. Luke's Episcopal Church in Buffalo Wyoming. It was built in 1889. Oddly enough, it's one of two St. Luke's in Buffalo, the other being a Lutheran Church across town.

Labels:

1880s,

Architecture,

Blog Mirror,

Buffalo Wyoming,

Christianity,

Churches,

Churches of the West,

Protestant,

religion,

Sunday Morning Scene

Location:

Buffalo, WY 82834, USA

Saturday, February 20, 2016

Friday, February 19, 2016

Friday Farming: Farmer John Boyd Jr. Wants African-Americans To Reconnect With Farming

African American farmers in Texas, April 1939. Note the horse hames.

This is a really interesting short interview that touches on one of the lost demographic stories of the US since the end of World War Two:

Up until mid 20th Century a huge percentage of African Americans worked on the land. Quite a few worked on land they didn't own, and no doubt that's why they have declined in that role to the present day. Heavily concentrated in the American South, during World War One and then again during World War Two African Americans from the South started migrating up into Eastern and Midwestern cities. When Robert Johnson wrote about wanting to go to "my sweet home Chicago" in 1936, he was expressing an aspiration that more than a few Southern blacks had at the time.

The great migration really wrecked that in a way that it didn't for other demographics. There are still black farmers, but not like their once was. Given that a lot of black farmers farmed on sharecropping operations that's not too surprising, but it is a huge change in the farming demographic that should be lamented.

The great migration really wrecked that in a way that it didn't for other demographics. There are still black farmers, but not like their once was. Given that a lot of black farmers farmed on sharecropping operations that's not too surprising, but it is a huge change in the farming demographic that should be lamented.

The African American legacy on the land shouldn't be forgotten, nor should it be lost. Would that it could be somewhat restored, although with land prices being what they are that would be quite a chore in this economy.

Labels:

Agriculture,

Blog Mirror,

Commentary,

Ethnicities,

Friday Farming,

Music

Lex Anteinternet: And the Economic news gets starker.

I haven't run one of these grim items on the local economy for a month now, with this being the last one:

This past week, however, prices went up, in spite of the news that Iran was about to place 4 bbl/day on line. Some of the OPEC countries and Russia were beginning to get in line, and there was a day when there was a sharp escalation of the price. Of course, sharp in this context doesn't put the price up around $50/bbl where it seems to need to be, but it was hovering around $40/bbl.

Yesterday, however, it was sinking again.

Today we read in the paper that Ultra has hired Kirkland & Ellis, the bankruptcy firm that shows up in all of these bankruptcies and which we recently read that Chesapeake was consulting with (although they say they aren't taking bankruptcy). And Cloud Peak (coal, but still in good shape) and Marathon (which downsized earlier) posted losses for the last quarter.

When the price started to climb a bit I thought that perhaps it had sunk to the pint where the low prices were no longer sustainable. I could have been premature on that.

Lex Anteinternet: And the Economic news gets starker.:There were several intervening bad stories in the meantime, but given at there's been so many, you reach a "what's the point" type of location.

Lex Anteinternet: Lex Anteinternet: Lex Anteinternet: Lex Anteintern...: And now the price of oil is down to. . . $29.00 bbl.Wyoming sweet crude is down to about $19.00 bbl. Wyoming sour crude is

now down to about $9.00 bbl. It was at $76.00 bbl in June 2014.

Fairly clearly, those are not economically sustainable prices.

This past week, however, prices went up, in spite of the news that Iran was about to place 4 bbl/day on line. Some of the OPEC countries and Russia were beginning to get in line, and there was a day when there was a sharp escalation of the price. Of course, sharp in this context doesn't put the price up around $50/bbl where it seems to need to be, but it was hovering around $40/bbl.

Yesterday, however, it was sinking again.

Today we read in the paper that Ultra has hired Kirkland & Ellis, the bankruptcy firm that shows up in all of these bankruptcies and which we recently read that Chesapeake was consulting with (although they say they aren't taking bankruptcy). And Cloud Peak (coal, but still in good shape) and Marathon (which downsized earlier) posted losses for the last quarter.

When the price started to climb a bit I thought that perhaps it had sunk to the pint where the low prices were no longer sustainable. I could have been premature on that.

Monday, February 15, 2016

Lawyers and the Challenges of the Electronic Age