Churches of the West: St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, Basin Wyoming:

This is St. Andrew's Episcopal Church in Basin Wyoming. This small town Episcopal Church fits into the Gothic style, in our view. I don't know anything else about it, other than that its coloration is unusual for a wooden church.

Ostensibly exploring the practice of law before the internet. Heck, before good highways for that matter.

Sunday, September 24, 2017

Sunday Morning Scene: Churches of the West: St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, Basin Wyoming

Labels:

Architecture,

Christianity,

Churches,

Churches of the West,

Protestant,

religion,

Sunday Morning Scene,

Trailing Posts,

Wyoming,

Wyoming (Basin)

Location:

Basin, WY 82410, USA

Saturday, September 23, 2017

Movies In History: Once again, getting things right in time and place

Earlier this past week I posted this item:

Lex Anteinternet: Movies In History: Wind River: I often dread watching modern movies set in Wyoming (I tend to give the older ones a pass) as they get things so wrong. And, of course, as...

What, you may ask, does this have to to with history?

Well, dagnabit, it's my blog and I can post on what I want to. So there.

Well, beyond that, perhaps a bit more than we think, although I will frankly admit that posting that item in the Movies In History category is stretching it, a lot.

But here's my point.

Movies about contemporary times attempt to portray a story in time and place, just like movies set in the past do. Some do it well, and others not so much.

In either event, those films become a record in people's mind as to what things were like, whether they realize it or not. Errors, great and small, preserved in films; people and dinosaurs lived at the same time. . . Frontiersmen of the 1860s were carrying cartridge arms as a rule. . . . cowboys wore Levis. . . everyone in the 1970s was under 30 years old, hip, cool, and into bikinis. . . . all Vietnam veterans are crazed killers. . . no wait, all Vietnam veterans for forsaken heroes. . . . and so on, tend to get stuck there. Perhaps ironically its often later more accurate films that get things straightened out. McCall is still carrying a cap and ball revolver in the 1870s? Everyone in Lonesome Dove is wearing wool trousers? You get the point.

So, on a film such as Wind River, a depiction matters in various ways, again great and small, as all such depictions do.

If you are from the Rocky Mountain West, and have watched the films set here, as a rule you will have been laughing, or crying, in the isles over wacky inaccurate portrayals of the region. Really off the mark settings and portrayals are too darned numerous to mention. A few real off the mark examples would suffice, such as the bizarre portrayal of the modern prairie in Bad Lands which actually held that you could see city lights in Montana and Cheyenne Wyoming from the prairie simultaneously. Or the goofball weird accents featured in portrayals like The Laramie Project (golly shucks alive Mablejean, ahh just dooon't knew what to make of it alllll, sakes alive). Or the I'm moving to Wyoming and quitting my minimum wage job and buying a ranch (as if).

To see a film that is set in the region in contemporary times and doesn't blow it is frankly amazing.

Which does leave me wondering about so many portrayals of here and there in the past in different settings. That gross exaggerations are taking in such musty classics as Sergeant York are obvious, but what else really misses the mark?

Labels:

Commentary,

Movies,

Movies In History,

The Moving Picture

Best Post of the Week of September 17, 2017

Labels:

Best Posts of the Week,

Trailing Posts

Poster Saturday: "United Russia"

Russian Civil War era poster. This is a pro "White" forces poster, with the red dragon representing the Red Army.

Labels:

Poster Saturday,

Posters,

Russia,

Russian Civil War,

Trailing Posts

Friday, September 22, 2017

More Sports News. . . the Midwest Oilers return home.

While I don't follow sports much, yesterday I ran this, which I found interesting:

Lex Anteinternet: Sports News: I rarely read it, but today's Tribune sports page has two items of interest. First, Casper is getting, for the third time, a non yo...

And today I'd note that the Midwest Oilers are reported to have returned home to their own field.

People tend to forget, for some reason, that Natrona County doesn't have two high schools. It has four, or 4.25 if you count Pathways, which you probably better do before its down and out for the count as closed (or before it's converted, as it should have been. . . maybe . . into an actual high school). One of those high schools is Midwest.

Midwest's school used to be a football titan here locally. This, of course,, way back in the day prior to transportation being very good. In those days, the sons and daughters of the oilfield workers in Midwest (and probably a few sons and daughters of Navy personnel stationed on Navy Row in Midwest who were assigned to the Naval Petroleum Oil Reserve) had to go to school there. Many still do, but some now drive to other schools or are driving by their parents. At least some people from Midwest that I know attended school in Kaycee, for example, which is in the neighboring county.

And the oilfield there just doesn't require the workforce it once did. The NPOR is closed. Trends in technology and production have reduced Midwest and neighboring Edgerton to shadows of their former selves, even though they are still there. The evolution of high school sports has meant that the Oilers and the other two high school teams are no longer in the same class and don't play against each other.

The times have long passed since Midwest played the Casper teams. . . or had that the town had its own newspaper for that matter.

But the team was a local giant once.

Well, the schools there still have a swimming pool anyway. . . .

Labels:

football,

Midwest Wyoming,

Sports,

The Swimming Pool Bond Issue,

Wyoming

Location:

Midwest, WY 82643, USA

Friday Farming: School Victory Garden, September 1917

Labels:

1910s,

1917,

Agriculture,

Friday Farming,

Garden,

World War One

Location:

Pennsylvania, USA

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm 1917. Released this day in 1917. . .

I'll leave you to your own opinions on the well known film.

Labels:

1910s,

1917,

1917 at the movies,

Movies,

The Moving Picture

Camp Sherman, Chillicothe, Ohio. September 22, 1917.

Labels:

1910s,

1917,

Army,

Ohio,

panographic photographs,

panoramic,

The Big Picture,

Trailing Posts,

World War One

Location:

Chillicothe, OH 45601, USA

Thursday, September 21, 2017

And now we're going to close one. . .

Yesterday, I posted this:

About 1,000 students short, in fact.

Closing elementary schools, and not filling up a "campus" of the other four high schools (yes, there's four, not two, like people so often wish to believe).

When things started to slow down a couple of years ago, I was defending the deposition of a businessman in Riverton who commented that the root of the school funding problem was over construction and over spending. I don't know if that is, but it does seem that the current funding model is broken. Here in this district we're closing an elementary school for the second year in a row, it seems, while we're in a slow panic about not being able to fill up a very expensive new structure. That is bad.

But it was predictable as well.

Laissez les bon temps roule, we're some times told.

Yes, but keep in mind that les bon temps are often followed by les mal temps, particularly with our economy.

And we haven't even seen what the completion of the two major projects here locally will mean as they start wrapping up over the next year.

Lex Anteinternet: Hindsight: The lost NCHS swimming pool and the Pa...:Today the news comes that the district enrollment is so declined at the grade school level that the closing of a school is nearly inevitable, after this academic year.

The Star Tribune has this headline this morning:Pathways' enrollment remains low, but principal says new system, 'baby steps' will bring facility to capacity

About 1,000 students short, in fact.

Closing elementary schools, and not filling up a "campus" of the other four high schools (yes, there's four, not two, like people so often wish to believe).

When things started to slow down a couple of years ago, I was defending the deposition of a businessman in Riverton who commented that the root of the school funding problem was over construction and over spending. I don't know if that is, but it does seem that the current funding model is broken. Here in this district we're closing an elementary school for the second year in a row, it seems, while we're in a slow panic about not being able to fill up a very expensive new structure. That is bad.

But it was predictable as well.

Laissez les bon temps roule, we're some times told.

Yes, but keep in mind that les bon temps are often followed by les mal temps, particularly with our economy.

And we haven't even seen what the completion of the two major projects here locally will mean as they start wrapping up over the next year.

Sports News

I rarely read it, but today's Tribune sports page has two items of interest.

First, Casper is getting, for the third time, a non youth league baseball team. The first game will be played on May 25.

This team will be a collegiate league team. Apparently that means that its a wooden bat team and that the teams are made up of college players who play during the spring and summer.

Let's hope this one sticks. Our last two teams; the Cutthroats (named for the native trout) and the Rockies/Ghosts had some loyal fans but were moved. Its hard not to note that with each addition we step one step further away from the major leagues but still. . . and indeed maybe this one will work.

Casper, it should be noted, had a vibrant adult baseball league in earlier eras. Indeed our packing house sponsored one, named of course the Packers. And the schools, decades ago, had high school teams. There are still really active youth leagues, but that's all.

The other news was that boxing great Jake LaMotta died.

A truly great middleweight and light heavyweight boxer from the golden age of boxing, he is perhaps best known today to most folks due to Robert DiNiro's portrayal of him in the movie Raging Bull, the greatest boxing movie ever made. Married seven times and known to be volatile inside and outside the ring, in some ways he symbolized a certain aspect of boxing when it really mattered as a sport. Here's hoping that he finds rest as he's passed on.

Labels:

baseball,

boxing,

Casper Wyoming,

Sports

Things my parents did that nobody does anymore I: Mend Socks

Well, not so much my parents, but my mother.

Original caption: "Mending socks for the American soldiers. Bureau of Refugees,

Toure. (See number 7676) Refugee woman mending socks for the American

soldiers at Toure under the direction of the AMERICAN RED CROSS. This is

part of the great salvage work that is making socks, sweaters, etc.

that have been worn, as good as new at a small cost, while at the same

time the women are enabled to support themselves".

People just don't do this anymore. When socks wear out, they toss them out (although I'll confess, perhaps oddly enough, that my socks have to be pretty darned worn out before I thrown them out. . . a hold over, I suppose, from my poor student days).

My mother darned socks her entire life. When I was a kid, she'd darn my worn socks. I hated that as the wool she'd use to do it rarely matched the socks in color (although why would that matter) and wearing darned socks is not all that comfortable really. But it must not have mattered to her, as she did it right up until her mind was stolen by age in her advanced old age.

Original caption: "Washington, D.C. Lynn Massman, wife of a second class petty

officer studying in Washington, D.C., darns socks in the afternoon while

baby Joey has his nap".

She must have learned this skill at home, no doubt. And no doubt at some point in her early life it came in handy.

Does anyone at all do this now? I'm guessing not many.

The Wyoming National Guard had gone to the Mexican boarder as infantry. . .

and they'd been mobilized in 1917 as such as well.

But they wouldn't be going to France as infantry.

Today the news hit that the unit was being disbanded and reformed into artillery, machinegun, and ammunition train units.

I'm not sure what happened to the machinegun and ammunition train elements, or if those actually happened. They likely did. I do know, however, that the artillery unit was in fact formed and is strongly associated with the Wyoming Guard during the Great War.

This was not uncommon. As the Army grew, the Army would be taking a lot of smaller units such as this and reconstituting them as something else. Both Regular Army and Guard units experienced this.

It's hard to know what the men thought of this. A lot, but not all, had served and trained as infantry just the prior year along the border. Did they have a strong attachment to it? Hard to know. Were some relieved, perhaps, that their role, in some instances, wouldn't involve serving as infantrymen in the trenches? We don't know that either.

But they wouldn't be going to France as infantry.

Today the news hit that the unit was being disbanded and reformed into artillery, machinegun, and ammunition train units.

I'm not sure what happened to the machinegun and ammunition train elements, or if those actually happened. They likely did. I do know, however, that the artillery unit was in fact formed and is strongly associated with the Wyoming Guard during the Great War.

This was not uncommon. As the Army grew, the Army would be taking a lot of smaller units such as this and reconstituting them as something else. Both Regular Army and Guard units experienced this.

It's hard to know what the men thought of this. A lot, but not all, had served and trained as infantry just the prior year along the border. Did they have a strong attachment to it? Hard to know. Were some relieved, perhaps, that their role, in some instances, wouldn't involve serving as infantrymen in the trenches? We don't know that either.

Wednesday, September 20, 2017

Movies In History: Wind River

I often dread watching modern movies set in Wyoming (I tend to give the older ones a pass) as they get things so wrong. And, of course, as a local, let alone being a native at that, I no doubt look at anything set in Wyoming with a highly critical eye.

This is the Wind River Indian Reservation Tribal Court in Ft. Washakie which also houses various other law related facilities including the police department and the jail.

This is the Wind River Indian Reservation Tribal Court in Ft. Washakie which also houses various other law related facilities including the police department and the jail.

.

And that would be all the more the case here as, while I rarely mention it here, the Reservation is one of the places where I'm licensed to practice law. I've accordingly spent a fair amount of time on the Reservation, although not in the Reservation's back country.

So, when a movie is set there, I"m prepared, I'm afraid, to eye it pretty closely. And that means I'm sort of set up to dislike it.

.

.

That didn't happen here at all.

.

.

Indeed, not only do I like the movie, but I'm amazed by how much about the state and the Reservation they got right. This is, indeed, a really rare film about modern Wyoming as it is mostly correct in all sorts of details.

Okay, to just summarize the film a tad, this movie is a murder mystery. It starts off when Animal Damage Control agent Cory Lambert is called to the Reservation to track mountain lions that have killed a steer belonging to his (ex) father in law, who is an Indian living on the Reservation. In tracking the cats, he finds the body of an Indian girl he knows is the high country. The Tribal Police respond and a female FBI agent responds. The development of the plot and the clash of cultures, a three way clash, ensues.

There's a lot that could go wrong with a plot like this from a local's prospective. Most of those things didn't go wrong on the other hand, but actually went quite right.

From the prospective of our reviews, we tend to look at the history of a thing, the culture of the setting and material details. We know that this is a contemporary movie, not a historical drama, but we're taking the same approach here and this film does really well.

Let's start with the "history" of the story, if you will.

Former Army stable, now BIA structure, on Ft. Washakie.

Crime, particularly crime associated with alcohol and drugs, is a huge problem on the Reservation, as Reservation authorities themselves will freely admit. In fact, the Wind River Reservation is "dry" in that alcohol sales are banned on the Reservation, an act that the Tribal Council took quite a few years ago Drugs are also a big problem on the Reservation and just a few years ago a fairly large DCI bust occurred there. And some big occasional acts of violence occur there as well.

The film mentions at one point how many Indian women simply go missing in the United States and that no statistics on this are kept. I was unaware of that, but I am aware of one case here locally in which an Indian woman's body was found by a sheep rancher I knew and it took years, and a very interested coroner, to identify the poor woman's body. She'd been murdered and left out in the prairie. So much of this feels very familiar.

One thing, and not a good thing, that feels very familiar in the film, which is associated with that, is the haphazard fashion in which so many young people in this state are left to live their lives. There's a comment early on about the appropriateness of an 18 year old girl being left to her own devices, but that's not so much an Indian thing here as it is a cultural thing. That too sounds all too familiar.

Former Army structure on Ft. Washakie, now used by the BIA.

The regional occupations, which might surprise some people, are spot on. There are Animal Damage Control agents in the state. Not many, but a few, as well as county trappers. To see one made the main protagonist and indeed the hero of the film is refreshing. The Reservation really does have a Tribal Police force (it has for over a century). I don't know how thickly staffed it is right now, and during the Obama Administration the Reservation was flooded with Federal police that were sent on some sort of anti terror funding effort, meaning that it was heavily policed for awhile. But the normal state of affairs puts the entire Reservation, which is indeed as big as Rhode Island, in the hands of just a few policemen. Again, I don't know how many, but I think a good example of what they face is provided by an advertisement I saw years ago for the Reservation game warden. There was only one (and there might still be only one) and the advertisement provided that the applicant had "to be able to ride into remote areas on horseback and bring out a a suspect alone".

Think about that. 2,000,000 acres to patrol, and you have to be able to do it. . . .alone.

.

.

That scene in the film in which the FBI agent asks if they should wait for backup and the Tribal Police chief responds "This isn’t the land of backup, Jane. This is the land of 'you’re on your own'." is spot on.

As an aside, I once stopped in the

Haines General Store in Fort Washakie and saw that the truck of the

Tribal Game warden, a single cab Dodge, was in the parking lot. A Ruger

Mini 30 was prominently mounted to the dash. Not exactly the AR of

current police fame, but I bet that guy, self equipped, knew how to use

it.

In terms of the physical portrayal of the region they also did a very good job. I know that much of the high country scenes were filmed in Idaho, and I've never been in the high country of the Reservation, but there is high country on it and I'll give it a pass. The scenes of towns and dwellings, including a certain horrifying trailer, look pretty familiar. The unusual habitation pattern of the Reservation, as opposed to the rest of Wyoming, in which there are a lot of dwellings here and there, is correctly portrayed. I had to debate in my mind if a scene showing Fort Washakie was shot there or not (I'm sure it wasn't) but the fact that I had to ponder that about a place I've been to many times says something. The prairie scenes are correct. And there is oil and gas development on the Reservation. There's one short shot of Lander which is actually of Lander.

The cultural portrayal is also very good.

The Wind River Reservation is the home to two Indian Tribes, the Shoshone and the Arapaho. That doesn't directly come up in the film but it's hinted at by those who know what to look for. For those familiar with the Tribes, European names are more common in one than the other, with Anglicized Indian names being more common in that other. Both show up in the film.

The tension between the Indians and the non Indians is subtle in the film, and its subtle in reality as well. Likewise the strong identification of a resident non Indian with Indians is something that occurs in reality as well. The highly rural and blue collar nature of nearly all the work depicted is also spot on for the state. The possible relocation of Lambert's ex wife to Jackson for a "better" job, working in hotels in Jackson, is the sort of thing that would really be regarded as a better economic move for many in the state.

The survival of the endangered Indian languages, not in daily primary use but still hanging on, is depicted in one scene and likely to the surprise of most people who live elsewhere. Indeed, the context in which it is shown, to deliver an insult to an outsider, is something I'm actually aware of occurring in a slightly different fashion. Likewise, the survival of some distinct Indian cultural practices is correctly portrayed.

Very unusually, the regional accent is correctly delivered, which it almost never is.

The main protagonist speaks with the correct Rocky Mountain region accent, the first time I've ever seen this portrayed in film. A subtle accent which is somewhat like the flat Midwestern accent, it is different and tends to have a muttering quality to it. For some really odd reason, most films set in modern Wyoming tend to use a weird exaggerated drawling accident that doesn't exist here at all, and which sound amazingly bizarre to our local ears. Speech as portrayed in accent form by something like The Laramie Project just don't occur here at all, but the speech delivered by Corey Lambert in the film is spot on. Even some of the phrases that show up in the film, such as a dissing of Jackson, are actually used here.

In terms of material details, the film is also amazingly accurate. The vehicles, a minor detail I suppose but an important one none the less, are correct for the region and the conditions. . . pickup trucks and snowmobiles. Clothing details are correct, including headgear for the region and outdoor clothing.

Firearms, which figure prominently in this film, are also correct for what we'd expect to find. The law enforcement officers in the film are all equipped with the current 9mms popular with law enforcement officers with one exception, that being the Tribal Police chief who is equipped with a M1911, something we'd find to be appropriate for that character. The Federal hunter was surprisingly accurately equipped. In the beginning of the film he's shown using a bolt action rifle which is somebody in that role in this region would be equipped with. Something that appeared in the trailers which I was prepared to criticize was that the same character was shown using a Marlin Model 1895, but in the film its revealed that this is a scabbard rifle for carrying on a snowmobile, in which case it does in fact make sense. A surprising moment for me was when he was shown to carry a large caliber revolver in a holster slipped on to a broad leather belt, as the evening I saw it I was just back from antelope hunting and I myself carry a large caliber revolver in a holster slipped on to a broad leather belt. I'm surprised by them getting a regional detail like that right. About the only firearms item I'd criticize is the appearance of a selective fire M4 in one scene but the use of M4 type carbines in the role that they're shown in would be correct.

So the film is perfect, correct?

No, I'm not saying that. But I am saying that they got most things right.

So what did they get wrong?

Well one thing is that drilling rigs operate year around in this region and do not shut down for the winter. That just doesn't happen. I understand why that was portrayed that way in this film, but that doesn't occur. And drilling rigs don't have security either, which is in part because they wouldn't need it as they don't shut down.

The sense of distance is off in the film as well. What are portrayed as long distances for the film would be short ones here. And one geographic feature that's shown to be reached inside of a day just simply could not be, although again I understand why that was incorporated into the film. Somewhere in the film there's a joke about going 50 miles to travel 5, which is true enough, but in reality its more like 150 miles to travel 15.

A minor matter is that a scene of what is supposed to bet he courthouse in Lander is most definitely not of the courthouse in lander. But that's not really so much of a complaint here, as simply something I'm noting. I know why they chose the building they did, perhaps. In movies they like their courthouses to look like courthouses, and the one in Lander really doesn't that much. But that, as noted, is not a big deal.

The survival of the endangered Indian languages, not in daily primary use but still hanging on, is depicted in one scene and likely to the surprise of most people who live elsewhere. Indeed, the context in which it is shown, to deliver an insult to an outsider, is something I'm actually aware of occurring in a slightly different fashion. Likewise, the survival of some distinct Indian cultural practices is correctly portrayed.

Very unusually, the regional accent is correctly delivered, which it almost never is.

The main protagonist speaks with the correct Rocky Mountain region accent, the first time I've ever seen this portrayed in film. A subtle accent which is somewhat like the flat Midwestern accent, it is different and tends to have a muttering quality to it. For some really odd reason, most films set in modern Wyoming tend to use a weird exaggerated drawling accident that doesn't exist here at all, and which sound amazingly bizarre to our local ears. Speech as portrayed in accent form by something like The Laramie Project just don't occur here at all, but the speech delivered by Corey Lambert in the film is spot on. Even some of the phrases that show up in the film, such as a dissing of Jackson, are actually used here.

Firearms, which figure prominently in this film, are also correct for what we'd expect to find. The law enforcement officers in the film are all equipped with the current 9mms popular with law enforcement officers with one exception, that being the Tribal Police chief who is equipped with a M1911, something we'd find to be appropriate for that character. The Federal hunter was surprisingly accurately equipped. In the beginning of the film he's shown using a bolt action rifle which is somebody in that role in this region would be equipped with. Something that appeared in the trailers which I was prepared to criticize was that the same character was shown using a Marlin Model 1895, but in the film its revealed that this is a scabbard rifle for carrying on a snowmobile, in which case it does in fact make sense. A surprising moment for me was when he was shown to carry a large caliber revolver in a holster slipped on to a broad leather belt, as the evening I saw it I was just back from antelope hunting and I myself carry a large caliber revolver in a holster slipped on to a broad leather belt. I'm surprised by them getting a regional detail like that right. About the only firearms item I'd criticize is the appearance of a selective fire M4 in one scene but the use of M4 type carbines in the role that they're shown in would be correct.

So the film is perfect, correct?

No, I'm not saying that. But I am saying that they got most things right.

So what did they get wrong?

Well one thing is that drilling rigs operate year around in this region and do not shut down for the winter. That just doesn't happen. I understand why that was portrayed that way in this film, but that doesn't occur. And drilling rigs don't have security either, which is in part because they wouldn't need it as they don't shut down.

The sense of distance is off in the film as well. What are portrayed as long distances for the film would be short ones here. And one geographic feature that's shown to be reached inside of a day just simply could not be, although again I understand why that was incorporated into the film. Somewhere in the film there's a joke about going 50 miles to travel 5, which is true enough, but in reality its more like 150 miles to travel 15.

A minor matter is that a scene of what is supposed to bet he courthouse in Lander is most definitely not of the courthouse in lander. But that's not really so much of a complaint here, as simply something I'm noting. I know why they chose the building they did, perhaps. In movies they like their courthouses to look like courthouses, and the one in Lander really doesn't that much. But that, as noted, is not a big deal.

The actual Fremont County Courthouse.

Another minor matter is that the name "Washakie" is mispronounced in the film and by an actual Indian actor, Graham Greene. In his defense, he's neither Arapaho or Shoshone but Oneida from Canada. And I sort of wonder if the pronunciation that's common here might actually be in error and I just don't know it (we use a lot of distinct pronunciations for things and people here that aren't pronounced the same way in their original languages). Still, it was surprising and somebody should have caught that.

A somewhat larger deal is that, as seems so typical, very view of t he Indian characters in the film are portrayed by Indians. That grates on the nerves of Indians and I can see why. There are Indian actors around, plenty of them, but its rare for all the Indian parts in a film to be portrayed by Indians. Whether or not its politically correct to say so, Indians do not look like people of European decent and simply assigning Indian roles and perhaps applying some makeup, no matter how effectively, to European American actors doesn't really change that.

And finally, people familiar with police procedures and regulation will have to note that there's at least a couple of instances in the story of this investigation in which its likely that special affairs would have had to be called in.

None the less, it's well worth seeing.

On a note, for those who may be inclined to see it, this film is violent. Very violent. Some scenes approach a Sam Peckinpah level of violence. There's a place for violence in a film, and then there's films that are simply violent. This film is sort of both. Potential viewers should be aware of that.

Labels:

Crime,

Daily Living,

Ft Washakie Wyoming,

Indians,

Lander Wyoming,

Mid-Week at Work,

Movies,

Movies In History,

The Moving Picture,

Wind River Reservation,

Wyoming

Location:

Wind River Reservation, WY, USA

Camp Sherman, Chillicothe, Ohio. September 20, 1917.

Labels:

1910s,

1917,

Army,

Ohio,

panographic photographs,

panoramic,

The Big Picture,

World War One

Location:

Chillicothe, OH 45601, USA

Tuesday, September 19, 2017

Now you know things are tense in Korea. . .

as why else would K-pop composer and

singer Lee Chan-hyuk enlist in the Korean Marine Corps?

Okay, all Korean men (not women, just men) have a mandatory military obligation.

But the ROK Marines are truly tough.

On joining, he has been quoted as saying that he joined in part “to build diverse experiences and improve my musical skills".

Hmmmm

Labels:

Korea,

Random snippets,

ROK Marine Corps,

South Korea

Location:

South Korea

Camp Grant, Rockford, Illinois. September 19, 1917.

Labels:

1910s,

1917,

Army,

Illinois,

panographic photographs,

panoramic,

The Big Picture,

World War One

Location:

Rockford, IL, USA

Roads to the Great War: A Last Word from the Red Baron

Roads to the Great War: A Last Word from the Red Baron: Thanks to Richthofen Fan Steve Miller for sharing this.

Labels:

1910s,

1917,

Aircraft,

Blog Mirror,

German Luftwaffe,

World War One

Monday, September 18, 2017

Hindsight: The lost NCHS swimming pool and the Pathways disaster.

The Star Tribune has this headline this morning:

Pathways' enrollment remains low, but principal says new system, 'baby steps' will bring facility to capacity

In that article, we learn the following:

Pathways Innovation Center’s enrollment is at roughly 250 students — a quarter of its capacity — but a school official said he was confident that number would grow as more students become aware of the facility’s offerings.

Will it grow?

I doubt it.

Not until it's simply made a third high school anyway, which I'd predict will occur within the next five to ten years.

Not that we really need one now. School enrollment has declined and people pulled out. Indeed, a lot of those people who pulled out around here were votes when the school bond issue on the swimming pool for NCHS was put up to vote several years ago, and failed.

And additional funding for Pathways was part of that same bond.

In retrospect, nearly everything about that bond issue was handled in correctly. Those of us who wanted a pool to replace the 1923 pool that came out when NC's massive reconstruction project started really were interested in that narrow issue. But the school district linked it to funding for Pathways. It turned out that a lot of people weren't keen on Pathways. I wasn't keen on Pathways for that matter and, frankly, if I'd been left with a yes or no decision on only that, I may have voted no. There must have been a big fear that a lot of people had similar views as the district bundled the pool with Pathways on the bond in the thought, I think, that support for the pool would carry the day.

That was a mistake. Opposition to Pathways, including opposition by teachers, may have sank the pool.

Acquiescing to the city's and county's request that a special election be held, rather than combining it with the general election, may have done it in also. The city/county was worried about the additional Once Cent tax passing, upon which the city depends for many things. Their thought was that if the bond issue proved unpopular all taxes might and that they might go down with the bond. That might have been right, but agreeing to their request meant that only voters who were really motivated to vote. . . yes or no. . came out. Not the mass of voters who have been generally more supportive of bonds and taxes. The district should have said no to the city/county. After all, the One Cent wasn't their problem.

Oh well, no use crying over spilled milk, eh?

I suppose.

But there's still plenty of room in the part of the athletic building to accommodate a pool. It could still be done.

But nobody is talking about it.

And perhaps that's not surprising. Now the economy here is hurting and there's no movement to do stuff like this. Once the reconstruction is over at NC and KW the number of heavy construction jobs here will plummet accordingly, however, so maybe this is a good time to consider it?

Of course nobody is actively agitating for it either. Once we lost the bond issue, we gave up. When something was done at NC on another athletic facility I noted that to a board member who in turn noted to me that a parents' group had backed it. What were we swimming fans doing? Well. . . nothing.

And I don't suppose we're going to either.

Still, it's frustrating. Football seems to get attention no matter what. The other sports, maybe they do, maybe they don't. Traveling around the state I see how that's so often the case. One high school here has a pool, the others do not. Rock Springs High School has a very nice set of tennis courts. Casper's high schools have. . . none. But then there's little room at the Casper schools, except for Pathways, for such facilities either, given that they're surrounded by the town. Rock Spring's high school must have been on the edge of town when it was built. Gillette's has a really nice aquatic center for its swimmers, which is also a city facility. Casper has an aquatic center but its not an Olympic pool.

Oh well.

Well, one thing that has happened that will impact high school sports here is that Gillette finally admitted it had two high schools, rather than one with two campuses. Our school district's going to have to take that path with Pathways. The campus approach is failing.

Labels:

Commentary,

Education,

Sports,

The Swimming Pool Bond Issue

If Heaven had looked upon riches to be a valuable thing . . .

If Heaven had looked upon riches to be a valuable thing, it would not have given them to such a scoundrel.

Johnathan Swift, Letter to Miss Vanhomrigh, August 12, 1720.

Johnathan Swift, Letter to Miss Vanhomrigh, August 12, 1720.

Labels:

1720s,

Johnathan Swift,

The written word

Sunday, September 17, 2017

Movies In History: Downfall

This movie is excellent.

Perhaps ironically best known to zillions of Youtube viewers for the highly lifted scene of a Hitler tirade, which has been adapted in caption form to every scenario known to man for comedic relief, this European production deals with the last days of Adolph Hitler and those in his Berlin bunker in the final days of 1945.

With the central figure somewhat being the true story of a secretary that was brought into Hitler's service during this period (I'm amazed that anyone would have agreed to be taken on at the time) the film is almost documentary like in dealing with those in Hitler's orbit as things came crashing down. Excellently acted, the film is gripping.

Material and historical details of the film are of the highest order. Uniforms, which in the case of the Germans amounted to a blistering array of the same, are correct. Weapons are also correct, including the unusual number of Stg44s that were in German hands by this time of the war. Characters appear to be portrayed precisely correctly based on what descriptions of those characters reveal.

The film is simply excellent.

The German language film is on Netflix and is well worth watching. Indeed, for a student of World War Two, it's a must.

Perhaps ironically best known to zillions of Youtube viewers for the highly lifted scene of a Hitler tirade, which has been adapted in caption form to every scenario known to man for comedic relief, this European production deals with the last days of Adolph Hitler and those in his Berlin bunker in the final days of 1945.

With the central figure somewhat being the true story of a secretary that was brought into Hitler's service during this period (I'm amazed that anyone would have agreed to be taken on at the time) the film is almost documentary like in dealing with those in Hitler's orbit as things came crashing down. Excellently acted, the film is gripping.

Material and historical details of the film are of the highest order. Uniforms, which in the case of the Germans amounted to a blistering array of the same, are correct. Weapons are also correct, including the unusual number of Stg44s that were in German hands by this time of the war. Characters appear to be portrayed precisely correctly based on what descriptions of those characters reveal.

The film is simply excellent.

The German language film is on Netflix and is well worth watching. Indeed, for a student of World War Two, it's a must.

Labels:

1940,

1945,

Germany,

Movies,

Movies In History,

The Moving Picture,

World War Two

Movies In History: 1898, Our Last Men in the Philippines

This is a Spanish film dealing with the apparently true story of a Spanish outpost in the Philippines that held out well after the Spanish surrender to the United States in the Spanish American War. It's the second Spanish film on this topic, with this one being made in 2016 and the earlier one being filmed, I think, in the 1940s (which somewhat makes sense, given the politics in Spain at the time).

Spanish soldiers of this period in their summer uniforms, which were blue and white.

I don't know what the earlier film is like, but this one is only so-so. It was worth watching, but not exactly great. The film deals with the protracted struggle of a Spanish outpost that takes refuge in a village church against Philippine forces which were fighting Span in the 1890s and were quickly, after that, fighting the United States. The story is a sad one, which it wold almost have to be, given the nature of the actual events.

In terms of portrayal, there seem to be weaknesses in various character portrayals from my prospective, but then I know nothing about the actual events. The Philippine forces seem too well equipped, and even uniformed compared to what was likely the case, and some of the lurid portrays of the village are highly unlikely to have reflected reality given the Catholic Philippine nature of the region being portrayed. The Spanish equipment and uniforms, however, appear to be quite accurate.

This film is available on Netflix, which is really the only reason I happened to catch it. Very few films deal with the topic of the Spanish in the Philippines in this late period, and so it was perhaps worth watching on that account.

Movies In History: There Will Be Blood

I saw this film on Netflix awhile back and meant to put in a review at the time.

I didn't get back around to it as, quite frankly, I had sort of a M'eh reaction to the film. I was impressed, but I wasn't. That's largely still the case, and frankly I think that the plot development and perhaps the acting is the reason why.

Based upon the Upton Sinclair novel Oil!, the oddly named There Will Be Blood follows the story of an early 20th Century oil prospector, who starts off as a silver prospector, on his rise. During that path, he takes on the infant son of one one of his partners who is killed in an accident and raises him, incorporating him in activities, life and schemes. After learning of an almost certain oil play in Texas, they travel there and encounter the second pivotal figure of the film, a young homesteader's son who is some sort of devout, and in this film oddly acted and grossly exaggerated, free lance Protestant minister.

The story is sort of, but only sort of, a morality play of a virtually Medieval type. The central tenant of the film, I guess, is that greed corrupts and corrupts everything it touches. Some of the portrayals are so over the top, however, that I found the film impossible to like, and indeed really only found the secondary characters, like the main protagonist's son, to be interesting and well done.

In terms of material details, the film is excellent. Indeed, that's why I watched it all the way through. Clothing and various such details are highly accurately portrayed. The oil field equipment, including cable tool drilling rigs, are also accurately portrayed. All that couldn't overcome the defects in the film for me, however, which I'd guess just came down to that the film is odd in some fashion, and that oddness seemingly could not be overcome. It was like drinking slightly sour milk. Best avoided.

Labels:

Movies,

Movies In History,

Petroleum,

The Moving Picture

Sunday Morning Scene: Churches of the West: First Baptist Church, Worland Wyoming

Churches of the West: First Baptist Church, Worland Wyoming:

This is the First Baptist Church in Worland Wyoming. I"m not entirely certain how to categorize the architecture of this church, which has a certain New England style to it.

This is the First Baptist Church in Worland Wyoming. I"m not entirely certain how to categorize the architecture of this church, which has a certain New England style to it.

Labels:

Architecture,

Blog Mirror,

Christianity,

Churches,

Churches of the West,

Protestant,

Sunday Morning Scene,

Wyoming (Worland)

Location:

Worland, WY 82401, USA

Saturday, September 16, 2017

Roads to the Great War: Hollywood and the Great War

Roads to the Great War: Hollywood and the Great War: Click on Image to Expand The "Golden Age" of Hollywood drew on a great number of World War I veterans. Presented here is...

Labels:

1910s,

Blog Mirror,

Movies,

Movies In History,

World War One

Best Post of the Week of September 10, 2016

Best Post of the Week of September 10, 2016.

The 102nd Infantry Regiment, United States Army (Connecticut National Guard). September 10, 1917.

The dogma lives loudly within you

The tangled web. The botched morass of American Immigration and the Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals

North Korea. So what are the options . . . and why do they want a bomb anyway?

Labels:

Best Posts of the Week,

Trailing Posts

Friday, September 15, 2017

North Korea. So what are the options . . . and why do they want a bomb anyway?

The very first atomic explosion, 1945. The US device at this time was an exception to what would become the rule. . . it was an offensive weapon. North Korea's nuclear missiles stand a frightening chance of becoming yet another type of exception, and also an offensive one.

If a person is going to urge action, like I did recently on the menace of North Korea, maybe they ought to stay what sort of actions can be taken.

So we look at that in regards to North Korea.

Frankly, none of the options are great.

We'll get to that in a moment. But if we're going to look at options, particularly options that might involve war, perhaps we better ask a question first, that being; why does North Korea even want nuclear armed missiles?

Oh surely you jest. . . you may be thinking.

No, I'm not.

It's a question that needs to be answered.

Nuclear Weapons. Why?

U.S. Atlas ICMB, our first, which came on line in 1957. The Soviet R& was introduced, first, that same year.

Consider this. Contrary to what people like to commonly assert, nations generally do not arm themselves with weapon simply because they can. They arm themselves with weapons that are useful and which suit their strategic purposes.

For this reason there are plenty of weapons that nations actually forgo atomic weaponry. Indeed, compared to the nations that could equip themselves with atomic weapons relatively easily but do not, the number that do is actually fairly small. They are: the US, Russia, the UK, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and now North Korea. South Africa is believed to have developed a bomb, for some odd reason but gave it up, illustrating what I've noted above. Lots of other nations could have atomic weaponry if they chose to, including, for instance, all of the European powers, Canada and Brazil. But they don't. Quite frankly that's because they're of very limited utility, but also because most nations that don't have a bomb would be hurt by having one, or they're close allies of some nation that has a bomb and therefore any purpose they'd achieve in acquiring one would be pointless.

North Korea, however, is an exception.

And that's what should scare us.

So what are the purposes in having a nuclear device? Well, there are three. In order of importance, they are: 1) a defensive purpose, 2) prestige, 3), an offensive purpose.

That's right, prestige is a purpose in acquiring an atomic weapon, or it once was. That's why at least to of the countries in the list, the UK and France, developed atomic weaponry, or at least its part of the reason.

Let's take a look at each of these reasons.

Long serving Tu-95, the Soviet Bear bomber best known for its extended maritime patrols.

USAF B-52. The B-52 entered service the same year that the Tu-95 did. It was a much more advanced aircraft and it also remains in service to this day.

1. Defensive.

August 29, 1949 ushered in the age of defensive nuclear armaments.

That was the date that the Soviet Union detonated RDS-1, their first atomic bomb, which was very similar to the "Fat Man" bomb the U.S. used on Japan during World War Two. That similarity was not accidental, the American government was heavily penetrated by Soviet spies at the time and had been dating back into the 1930s. And this penetration included the US's wartime nuclear program. The US was dense to this reality, to their discredit, but it was the case.

This isn't, of course, as history of Soviet spying in the United States. This is a discussion of nuclear arms and up until that 1949 date the US was the only nation that had nuclear weapons. After that date, that was no longer true. The Soviets couldn't instantly deploy a significant nuclear stockpile, of course, but they would soon enough. The long nuclear nightmare had begun.

A B-58 in flight in 1967. The B-58 was the first US supersonic strategic bomber and it was designed to drop nuclear weapons exclusively. Seeing one in flight a couple of years after this is one of the enduring memories of my childhood.

But, in spite of the way the public commonly imagined it, that was a defensive nuclear nightmare.

Nations that hold nuclear weapons for defensive purposes use them to deter other nations from doing something else. For the most part, they use them to deter other nations from using nuclear weapons on them, although sometimes that deterrence has been expanded out to deter, in one fashion or another, the use of conventional force as well. The theory, and one that has proven fairly correct in its application, is that no nation will attempt to use nuclear weapons on a nuclear armed state. Or, if expanded out, no nation will invade a nation or region if there's a realistic threat that this will bring a nuclear response (a much less credible threat, by the way).

This is the situation that developed fairly rapidly in the Cold War. Up until RDS-1 the US was the only nuclear armed state and while the US expected other nations to acquire the bomb, sooner or later, it also expected the use of it to be routine and the US itself was fairly indistinct on when it felt use of the bomb was strategically sound. After August 1949, while it would not really sink in fully for years, it became apparent that it was never strategically sound to deploy nuclear weapons as it would nearly always bring a nuclear response.

Indeed, while Americans tend not to really appreciate it, the Soviet bomb was defensive bomb from the outset. With an enormous conventional army that dwarfed those to the west, and with an impressive record of being willing to sustain mass causalities to defeat an enemy on the ground, the thought in the West did lean towards simply deploying nuclear weapons if necessary, and the Soviet thought ran towards preventing that from occurring. After the early 1950s, when the Soviets had an appreciable nuclear arsenal, that worry was effectively mitigated. While the United States never declared during the Cold War (contrary to common belief) that the US wouldn't use nuclear weapons first, or that it wouldn't use low yield (comparatively) nuclear weapons on the battlefield (and in fact it threatened to deploy them openly to Europe in the 1980s), and while the Soviets actually did declare that they would never use them first (and that they regarded any use of a nuclear weapon to be a "first use"), it was commonly understood that the US would never use them first. It was feared that the Soviets would, but with the benefit of hindsight it seems pretty clear that they wouldn't have either. That left the Soviet ground forces, in the event of war, safe (if nervous) under a nuclear umbrella and it likewise did the same for the US and its NATO allies. In the end, that's why the Soviets continued to develop their World War Two style massive armored army, and why the US and other NATO allies countered by developing high technology conventional armies. They planned to fight, if they had to, conventionally. Each side's nuclear weaponry deterred the use of the same by the opponent.

It was all defensive.

The USAF B-1,t he strategic bomber that was to replace the B-52 but which never did. It also remains in service.

Other nations have acquired nuclear arms for similar purposes, although often mixed with the motive that will be mentioned immediately below. Probably Israel's unacknowledged nuclear arsenal is the most notable example. Known to exist but never admitted, it's held to counter the use of nuclear weapons by any of its enemies and. . . maybe, to keep the country from being overrun at the end of the day. China's weapons, the UK's and France's all likewise fit into the defensive category. But at least with the UK and France, the next item is also of some consideration. . .

2. Prestige.

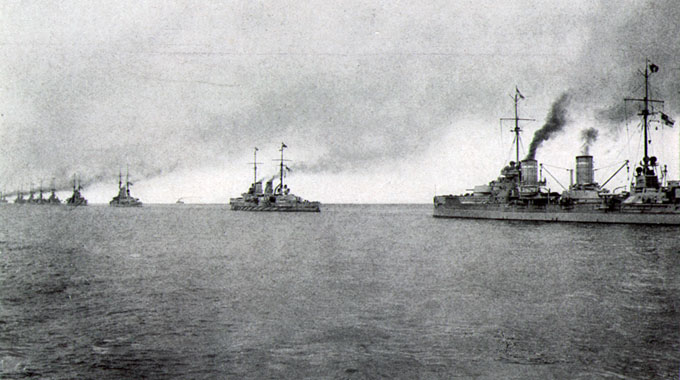

Imperial German High Seas Fleet. Yes, battleships were useful, but the super expensive weapon was also a matter of prestige. In some instances, the prestige of having battleships rivaled their utility, and their great expense made nations that had them very reluctant to risk them. The Germans and the British, during their battleship era, risked them against each other a single time.

It's odd to think of now, but there was an era in which having a nuclear arsenal was proof that you were a first world country of real weight.

Now, having a major tech industry fits that bill. Or maybe a really advanced economy. Or maybe a functioning health care system. But having nukes isn't. Not anymore.

It was once.

Coming out of World War Two much of the glory of the Western world lay in ruins. The United Kingdom was badly battered and kept rationing in place until the 1950s. France suffered major devastation and teetered on the brink of a communist revolution. Italy was prostrate, wrecked and given to crime of all types. Germany, formerly the major economic powerhouse of central Europe was reduced to rubble due to the final two years of round the clocking bombing that took place during World War Two, followed by intense fighting on its own soil. Things were pretty bad for Europe and European culture.

B-24 over Polesti during World War Two.

And Europe and European culture was the global standard. All the world powers had been European. The one nation that tried to contest that and join the club, Japan, was wrecked, including the devastation that was brought by the use of two atomic bombs by t he United States, although in fairness that paled in comparison to the devastation brought by conventional bombing and firing bombing, let alone over a decade, in Japan's case, of war.

Frankfurt, May 1945.

The United States, on the other hand, was looking pretty good. The country had suffered the loss of life, mostly of fighting men, during the war, but not as many. 407,316 fighting men, a shocking number by any standard, died or disappeared during the war while serving in the American armed forces. The British Commonwealth's loss was about the same, it should be noted, being 580,497 men from all branches of all of the various services that held a connection to Britain. 5,318,000 German fighting men died during the war by comparison. It's often noted that the majority of German combat losses were on the Eastern Front (a somewhat involved analysis, however, that's rarely done) and it should therefore be noted that the Soviets loss approximately twice that number themselves on the battlefield (Japan, Germany's ally, loss a little over 2,100,000 men out of a population that was actually larger than Germany's, Italy loss a little over 300,000 men on all of the European and North African fronts). None of this deals, of course, with civilian losses, which were substantial.

For democratic countries, and that matters a great deal, the impact of the loss of life is more intensely felt than in dictatorial ones. None of the Western democracies could have sustained the loss of life that the Germans, Soviets and the Japanese did (and one non democratic Axis power, having a population that leaned towards primitive democracy in any event, refused to do so, that being Italy). So the Western allies fought in a different style, emphasizing, as they would later in the Cold War, technology and firepower over human loss.

Be that as it may, the course of the war saw the technological advantage and industrial advantage significantly shift during the war. Armies may be the glory of dictatorships and wartime nations, but industry and a solid economy is the glory of a peacetime nation. For nations is some sort of cold war, and the Cold War isn't the only example of such, expensive weapons may give evidence of that. During World War Two it was actually the United Kingdom, not Germany, that was the economic and industrial powerhouse early in the war, although Germany was contenting for that title. By mid war the UK was sharing this position with the US. By the war's end, the US was the undisputed industrial and economic champion, providing weapons to every single allied nation and as well as cash. No other nation came close to comparing to the United States in these regards. When the war was over the United States was the only world power left standing, although the USSR was clearly contending for that position. The atomic bomb, which of course had been constructed with significant British assistance, symbolized that position.

Which is why the United Kingdom and France soon had their own. The UK, with US assistance at first, and then without it, and then with it again, developed their atomic weapon by 1952. France touched off its first experimental nuclear device in 1960, in the Algerian Saharan desert, while it was fighting with the FLN and others for control of that colony.* France was struggling to regain respect in the international community at the time having lost to Germany in 1940, having suffered severe internal conflict thereafter, having lost Indochina to the Indochinese and then being on the verge of losing Algeria, which had been one of its very first overseas colonies and which was regarded as an overseas department of France.** Having a bomb showed that these nations were still first rate, industrial, major powers.

And then something began to happen.

After the major World War Two players obtained the bomb it became fairly obvious that any major first world nation could have one, if it wanted to. But most opted not to, and the views about holding the bomb began to really change. The perpetual underlying terror that people endured during the 1950s and 1960s started to give way to an anti bomb sort of feeling perhaps best symbolized by literature and film of the period. Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb, probably best symbolizes that. Quite a bit different, as was Fail Safe upon which it was based (the book, that is, but there was a contemporary movie as well) from Strategic Air Command of a decade prior. By the time the bomb spread from first world nations to India having one became a matter of condemnation, which was the case for Indian when it acquired one. Ever since acquiring a nuclear device has been cause for contempt and those nations that have them have worked towards trying to reduce them. Joining the nuclear club, now, is somewhat like joining a leper colony. Nobody wants to be a leper and once you are one its really hard not to be one.

So much for prestige, which doesn't mean an isolated country like North Korea is aware of that.

3. Offense

Atomic mushroom cloud over Nagasaki.

The final reason, and by far the most frightening reason, for a nation to have a nuclear weapons is for offensive purposes.

Scary indeed.

This one, perhaps, doesn't require much explanation, but we'll give a little anyway. The concept here is that if war is diplomacy by other means, than any weapon is legitimate if you engage in it. This was basically the view that the United States had in 1945 when we used two atomic bombs on Japan. Whatever you think of the use, one way or another, the decision was made to drop atomic weapons on cities, as targets. Those cities had a military value, which is often forgotten, but that there would be massive and overarching loss of civilian life was known and at least a collateral aspect of their use. Again, while its not popular in most U.S. circles to think of them this way, they weapons were weapons of massive reprisal or, as some have claimed, terror.

Photograph taken from Honkawa Elementary School, photographer unknown, and not discovered until 2013. This photograph was probably taken about three minutes after the blast, although the common story credits it with being taken thirty minutes after the blast.

Irrespective of a person's view of the two atomic strikes by the US, which of course are the only wartime use of nuclear weapons ever, it is important to keep in mind that they came at a point at which the United States was the only nation in the world that had them. Additionally, when those strikes came, the entire world had become acclimated to massive airborne devastation. That doesn't answer any moral questions of any kind, really, but it puts their use in context as by that time quite a few people, including it would seem Harry Truman, had become numbed to massive devastation in wartime and the difference between the use of an atomic weapon and a mass fire bombing was one of degree to an extent An acknowledged difference in kind also existed but it was dimly perceived by some, but not by all.*** There was, moreover, no chance of reprisal strikes of any kind.

High altitude United States Army Air Force photograph following the atomic bomb strike on Hiroshima. Study of the photo in later years has revealed that the enormous cloud is actually the cloud from the firestorm, not the atomic strike. By this point in World War Two fire bombing by the USAAF of Japanese cities had become fairly common and accepted and almost as devastating as the nuclear strikes.

All that fairly rapidly changed after World War Two but it took a while to grasp the change. The USSR's acquisition of atomic weaponry in 1949 meant that, at least as to the Soviet Union, the use of atomic weapons was sure to bring an atomic reprisal, making use against the USSR problematic at best and effectively setting any rational conflict (key word being rational) back to the pre August 1945 status quo ante, maybe, albeit not in an acknowledged form. That this would spread to any potential uses as well was not immediately grasped but it soon came to be the case, and ironically perhaps it came to be grasped quickly by Truman.

For a period of time after World War Two the US defense establishment actually assumed that any future war would be a nuclear one and ground troops merely a trigger to that, and training in the Army (but not the Marine Corps) accordingly suffered. That this was not to be the case first became evident, to a degree, with the Korean War, to which the US committed heavily in a conventional form. During the war Douglas MacArthur, frustrated with Chinese entry into the war, asked for nuclear strikes against the Chinese who were vulnerable to it, relying as they did on mass staging areas in Manchuria, and Truman flatly refused. The first request to use nuclear weapons offensively, in the post World War Two era, was refused.

Not that the concept entirely went away right away. The French, who had not yet developed their own bomb, requested that the US deploy nuclear weapons on their behalf in the jungles around Dien Bien Phu in 1954. The request was seriously considered and the decision was basically made to agree to the desperate French request even though the US did not regard the French struggle in Indochina as a pure struggle against Communism. At that point Eisenhower brought in the Senate leadership and Lyndon Johnson, who was opposed to the idea, asked what the British thought of it. Nobody had thought of asking them up until that point, but it was agreed that this was the proper thing to do. Winston Churchill, who was back in office as of 1951, was flatly opposed to the idea in part as he regarded the French effort in Indochina as completely doomed. But for Churchill and Johnson, it's likely the United States would have deployed nuclear weapons to battlefield use in Indochina in 1954, a move that would have completely legitimized them in that deployment and which would have likely seen their use in similar form in later wars.

French troops (perhaps legionnaires) at Dien Bien Phu. The fate of the men depicted here was a bad one as the French were not able to retain the embattled post and it was eventually overrun, with survivors going into Viet Minh captivity in bad circumstances. The battle would haunt the 1950s and 1960s and formed much of the American thought surrounding the later battle at Khe Sanh during the Vietnam War, to which it bore eerie similarities.

They weren't used, however, and some suggestions that they be used in that fashion during the Vietnam War were flatly rejected as nuts. As time passed, the concept of battlefield use of nuclear weapons nearly died although it was briefly revived during the Carter and Reagan administrations in regards to "Neutron Bombs", a type of small nuclear weapon that generates a high lethal dose of radiation but which doesn't destroy anything.**** The concept died when the Soviet Union indicated that any such use would be regarded by it as lacking any distinction with any other nuclear weapon resulting in a full scale nuclear war.

That later experience came after Mutual Assured Destruction was a fully developed relationship between the US and the USSR, and that effectively converted everyone's nuclear arsenal to a defensive one, only to be used if the other guy used his first, and then to everyone's demise.

So, what's going on with North Korea? Defensive? Prestige?

Maybe.

But maybe their intent is offensive.

Surely, you jest.

Nope, surely I do not.

What's up in the Communist Hermit Kingdom?

Am I suggesting that North Korea intends to launch a nuclear first strike?

No, I'm not suggesting that either.

But I am suggesting it may be planning a conventional invasion of South Korea, protected, in its mind, by a nuclear umbrella. Indeed, the odd that they're planning such an event seriously are at least even.

And here's why.

Every country is a product of its own history and judges the world according to its experiences. This is both a plus and a minus, but more than anything, it's human nature.And in North Korea's history, and given its isolation, it's likely drawing a different lesson about launching a ground invasion of the South, for the second time, than we do. Let's consider that history and what it's likely teaching a person of extraordinarily narrow world view like 33 year old Kim Jong-un.

North Korea's history would teach a leader of that nation, assuming the leader didn't look too broadly, that armed invasions work, and are safe to conduct as long as some powerful force has your back. Moreover, current history would teach it that Korean reunification is growing further apart, rather than closer. Simple observation would teach it that the North increasingly offers very little that entices the South. National mission, or at least he expressed national mission of the leaders of that nation, require it to seek reunification. Economic necessity might as well.

So, if its to fulfill its self expressed national mission, it likely need to do it by armed force. Its not going to happen any other way, absent a collapse of the North Korean regime and the rescue of the North Korean people by the South, which is a very real possibility.

But armed force only make sense if it can succeed. And that's what history likely teaches to Kim Jong-un.

Consider the following.

The North Korean invasion of South Korean in 1950 almost worked. It only failed to reunify the country (which had been only apparent, after having a been a Japanese colony, very briefly) because the United States intervened to prevent that from occurring. Even at that, however, the US rescue barely worked at first. Following that, however, it nearly succeeded in doing in the North Korean regime and reuniting the country under the Southern government. That only failed to occur as the Red Chinese would not stand by to let North Korean fall and itself intervened in force, pushing the Western powers and the ROK army back to the 38th Parallel.

Late model T-34/85 tank knocked out by US, as the turret interestingly indicates, during the Korean war, on July 20, 1950. This tank was arguably the best battle tank in the world at this point in time and American tanks that would ultimately do well against it were of the very late war US heavy class which was soon to be our new main battle tank class. This tank epitomizes the North Korean experience in offensive warfare in every respect.

So what, you may ask, would North Korea have learned from that? Invasions fail?

Not hardly.

Indeed, large-scale offensive operations worked nearly twice during the Korean War, once when North Korea invaded the South and once when the United Nations crossed the 38th Parallel and nearly drove the North Korean army across the Yalu. In both instances the total defeat of the side on the defensive was prevented only by the massive intervention of an outside force. . the United States and associated powers in the case of the 1950 North Korean invasion and Red China in the case of the United Nations counteroffensive of the winter of 1950-51. Put another way, North Korea was prevented from obtaining victory by an American military "umbrella" and North Korea was saved from defeat by a Chinese military "umbrella". And following that, those umbrellas, ultimately ones held by two nuclear armed powers, have kept each side from launching a resumption of aggression since, although South Korea lost the desire to do so after the death of Syngman Rhee, its' first "president". There's no good evidence that North Korea has lost that desire itself. Indeed, massive tunneling and the like would suggest quite the opposite.

North Korean T-34/85 knocked out near the 38th Parallel after the brilliant Marine Corps amphibious landing at Inchon. If the proposed use of atomic bombs was the low part of MacArthur's tenure as supreme commander of the United Nations effort, the landing at Inchon was the high point.

So how would nuclear arms play into this?

In order to do that we need to look just a bit more carefully at the Korean War itself, if we are assuming that Kim Jong-un is deriving his views of the present by the lessons of the fairly short North Korean past.

The 1950 North Korean invasion of the South was a massive conventional military offensive. The North Korean Army was constructed in the model of the Soviet (not the Chinese) Red Army and was very well equipped with World War Two vintage Soviet weapons. It fought in the Soviet style. It was well trained in the Soviet context, which would compare poorly with the World War Two American model but which was still much better than the South Korean army of the day which was very poorly trained. Kim Il-Jung, for his part, was a veteran of the Red Army himself and would develop a personality cult around himself that frankly exceeded that of Mao or Stalin.*****

The only thing that stopped this armored juggernaut was the intervention of a much superior armed force, well equipped with modern weapons and used to fithign a modern war, the U.S. military.

North Korea was saved by an entity that was willing to endure mass casualties, the Red Chinese, but had the mass of men to lose.^

U.S. Marines fighting against the Chinese near the North Korean border with China at the Chosin Reservoir. The tank is a M26 Pershing which had been a heavy tank designed to take on late war German tanks of the Second World War, but which was sent to Korea essentially in the role of a main battle tank in order to take on the T-34. The M26 was the father of every American tank thereafter until the M1 Abrams.

The lesson to draw from that is that, or that might be drawn from that, is that a dedicated North Korean offensive might work under the proper conditions, although the United States stands in the way. The other lesson to be learned is that North Korean can never lose, that is actually be totally defeated, as long as it stands under somebody's "umbrella", that being a Chinese umbrella since 1950.

Now, before we go on to hear "but that's not the correct lesson", let's go one step further. Since 1954, when the armistice was signed halting the fighting, both nations have had an official policy of reunification. The United States effectively halted South Korea from resuming the war, which it was in fact tempted to do, early on. Had the US allowed it, the Korean War would have started back up in the late 1950s or the 1960s. We don't know what goes on north of the 38th Parallel, but chances are good that something similar has occurred there. We do know that North Korea has consistently prepared for n invasion, and even tunneled under the DMZ with tunnels large enough to contain entire divisions.

Perhaps the rational calculation that the United States and ROK military, which is now very good, would stop a North Korean offensive has kept North Korea from invading. Or perhaps the Red Chinese have threatened North Korea with dire implications if they tried it. We don't know.

We shouldn't assume that the calculation that they'd face well trained (and mostly South Korean) forces in an invasion, or that the United States would be involved, is sufficient in and of itself to prevent them from striking South. It might be, but we don't know that. We do know that their experience with surprise conventional attacks nearly worked, although in 1950 they were facing a largely untrained South Korean army rather than the highly trained one that they face now. Still, an Army modeled on the Soviet Red Army and drawing from its experience would know that surprise conventional attacks can work. World War Two, which dimly informs the North Korean Army, provides plenty of examples of that. That they themselves are willing to endure the casualties is apparent. If calculation of their chances has prevented them from launching south so far, it may be largely because they cannot possibly counter the USAF and they should know that.

But what also may weigh into it is that their guaranty from the Chinese may contain restraints. The Chinese entered the war last time as Red China could not bear the thought of an American ally on its borders. It was still truly at war with Nationalist China at the time and the strategic implications of that were too vast. Indeed, Chang Kai Shek offered Nationalist Chinese troops to the United Nations effort and the US rejected them, for obvious reasons. China, unlike the United States, does not maintain troops in North Korea, and of course, it doesn't need to. Its interests can be perfectly served simply by keeping its troops inside of China. Chances are high that China's promise to North Korea is limited to keeping North Korea from losing a war alone, and perhaps with the implied threat that if North Korean launches one, it's not saving it. Today China would not be strategically threatened by the Republic of Korea extending north to the Yalu and it knows it. Indeed, it might be economically aided by having an economically strong, Finlandized, Republic of Korean that was north and south of the 38th Parallel. It probably would be. North Korea probably knows that. Indeed, in the context of the current situation, chances are high that North Korea is looking more and more to Russia, which has its own interests simply in being disruptive towards the United States and Japan, and less, to the extent it can afford it, to Red China. That Red China and Russia would not be in any sort of significant coordination seems fairly apparent. Be that as it may, there's a strong chance that China has been the brake on North Korean aggression and the lack of certainty about its willingness to save North Korea may cause it to hesitate to act.

But the bomb would cure all that.

With an atomic bomb, of any type, North Korea can lay safe under its own umbrella, a nuclear one. It can launch a conventional strike against the South and use the bomb in any sort of threatening ways. It might simply indicate, should thinks go bad, that if South Korean or American troops go north of the 38th Parallel it will use nuclear weapons to its fullest capability, in a sort of Hitler in the bunker moment. That's the most likely scenario. Or it might threaten more broadly, say threatening the United States not to use air assets against North Korea, although that's a bluff that would likely be called so that's likely not it.

Can we say that is what North Korea wants nuclear weapons for. No. We don't know what their thinking is.

Could that be their thinking?

It certainly could be.

How likely is it?

Fairly likely.

Here's why.