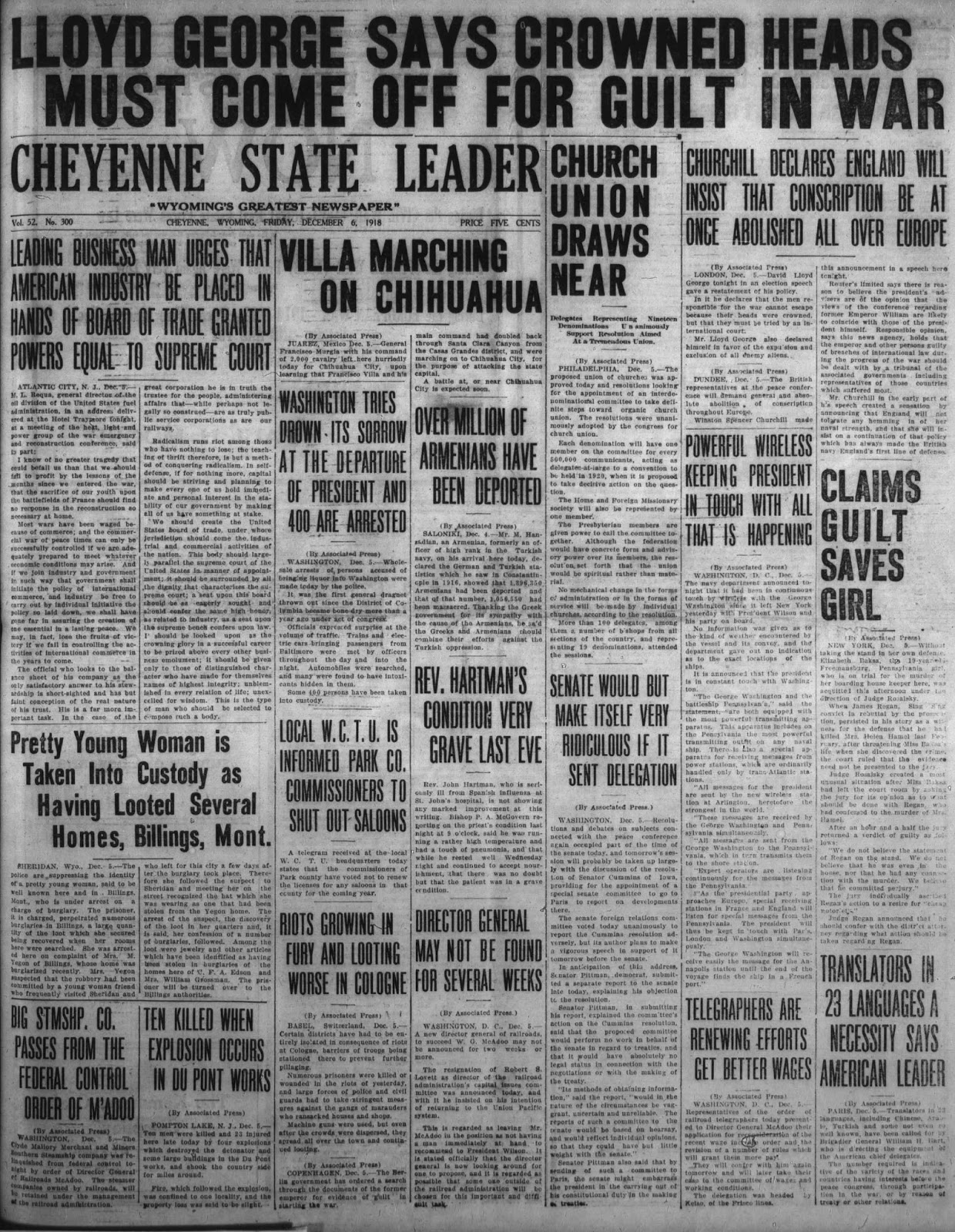

Painting of Canadian soldier on early occupation duty in Germany following World War One.

Recently, in another post, we posted the Allied areas of occupation following the Armistice in World War One.

It's worth taking a second look at:

December 27, 1918. The Collapse of the German Empire. The Rise of Poland. A League of Nations.

Contrary to what occurred after World War Two, the allied occupation following the Armistice of November 11 was quite limited in scope. This is also sometimes misunderstood. The occupation following the Second World War was intended to totally demilitarize and remake Germany. The 1918 one was not, but instead was intended merely to prevent a resumption of the war with the West. It was quite limited, but strategic, in scope.

Occupation zones following November 11, 1918. 'Armistice and occupation of Germany map', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/armistice-and-occupation-germany-map, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 15-Jun-2017

It's commonly noted that following World War One the various (Western) Allies occupied Germany, or that various units went into to Germany. That's true, but not that much was occupied, all things being considered, at least at first. But the story of the occupation is really convoluted and somewhat difficult to follow.

It's an important story, however, for what it didn't accomplish.

Immediately following the war, the Allies occupied the zones noted above. The point, as noted earlier, was to recover territory lost to the Germans during World War One and the Franco Prussian War, to run the Allied lines up to the Rhine, and to throw bridgeheads over the Rhine in case it was necessary to resume offensive operations, although the chance of that occurring was slim and the Allies knew that, which is demonstrated by the commencement of a partial demobilization nearly immediately. The zone assigned to the Americans for this, as also earlier noted, was surprisingly large and that assigned to the British was surprisingly small. Belgium,

whose army had to spend most of the war outside of its own country,

occupied quite a bit, in relative terms.

In the interior of Germany, however, i.e., nearly all of Germany save those regions south of the Rhine, the German provisional government was left in charge, and the German Imperial Army was at its service. That provisional government faced a titanic task, however, as Germany was in a state of early Russian Revolution style civil war, with Red soldiers, sailors and civilians openly challenging the government and fighting the Army in may location for control of the country and its future. And, as noted above, an entire province of Prussia, Posen, rose up in a Polish rebellion against Germany in an ultimately successful attempt to separate that province from Germany and join it to Poland. A second smaller revolution, because the territory is smaller, occurred in Silesia with the same goal after that one. Meanwhile, thousands of German soldiers were stranded in regions they'd been sent to by the German Imperial government which were beyond Germany's borders and some of them were still engaged in combat against Red forces in the East under commanders who continued to basically act autonomously and seemingly under some sense that the Crown or at least an Imperial government would revive.

Contrast this to the end of World War Two in which the German government completely ceased to exist, its Army along with it, and 100% of German territory was occupied.

An element of this is that because the war ended in an armistice, rather than a surrender, it was unclear to both sides how long it would take to negotiate a peace. It quickly proved to be the case that it was going to take a lot longer than supposed as arranging for such a peace was much more difficult than at first imagined. The November 11, 1918 Armistice, therefore, actually ran only until December 13, 1918, at which time it was extended in recognition of that. In the meantime, the Germans, by operation of the armistice, did in fact surrender their Navy which went, in large measure, to Skapa Flow. The surrender of the Navy was a further signal that whatever was going on in Germany and whatever it was capable of, it wasn't capable of resumption of a war against the Western Allies. During this period the Allies occupied the areas shown above.

The First Prolongation of the Armistice did not suffice to be long enough to establish a new peace, and on January 16, 1919, it was extended again. This allowed the negotiations on a peace treaty to commence on January 18, 1919. As is well known, the treaty that was arrived upon, while I frankly think it was a good and just one under the circumstances, was regarded by the Germans as harsh for a number or reasons we'll touch on when the time comes (maybe). The Germans at first refused to sign it and the German government then in power fell over the issue of signature. The new German government asked for certain clauses to be withdrawn indicating that if they were, they'd execute the treaty. The Allies, in turn, gave the new German government 24 hours to indicate acceptance or face a resumption of the war.

That threat was not an idle one. In June 1919 Germany was still in the midst of a revolutionary crisis which its army had not been able to put down, Posen had de facto separated, and the government remained highly unstable. The German Army, while not impotent, was obviously in extremely poor condition, suffering attrition by desertion, relying upon militias, and with no remaining industrial base to call upon. Faced with the threat of complete occupation, the Germans capitulated on June 23, 1919.

By that time the armistice that had ended the war itself was in its third prolongation, which ran to January 10, 1920. The formal agreement ending the war (not entered into by the United States) allowed the armistice to end and a new phase of occupation to commence.

The Treaty of Versailles allowed for the ongoing Allied occupation of the Rhineland, specifically providing:

Article 428

Article 429

- As a guarantee for the execution of the present Treaty by Germany, the German territory situated to the west of the Rhine, together with the bridgeheads, will be occupied by Allied and Associated troops for a period of fifteen years from the coming into force of the present Treaty.

- If the conditions of the present Treaty are faithfully carried out by Germany, the occupation referred to in Article 428 will be successively restricted as follows:

- (i) At the expiration of five years there will be evacuated: the bridgehead of Cologne and the territories north of a line running along the Ruhr, then along the railway Jülich, Duren, Euskirchen, Rheinbach, thence along the road Rheinbach to Sinzig, and reaching the Rhine at the confluence with the Ahr; the roads, railways and places mentioned above being excluded from the area evacuated.

- (ii) At the expiration of ten years there will be evacuated: the bridgehead of Coblenz and the territories north of a line to be drawn from the intersection between the frontiers of Belgium, Germany and Holland, running about from 4 kilometres south of Aix-la-Chapelle, then to and following the crest of Forst Gemünd, then east of the railway of the Urft valley, then along Blankenheim, Waldorf, Dreis, Ulmen to and following the Moselle from Bremm to Nehren, then passing by Kappel and Simmern, then following the ridge of the heights between Simmern and the Rhine and reaching this river at Bacharach; all the places valleys, roads and railways mentioned above being excluded from the area evacuated.

- (iii) At the expiration of fifteen years there will be evacuated: the bridgehead of Mainz, the bridgehead of Kehl and the remainder of the German territory under occupation.

Article 430

- If at that date the guarantees against unprovoked aggression by Germany are not considered sufficient by the Allied and Associated Governments, the evacuation of the occupying troops may be delayed to the extent regarded as necessary for the purpose of obtaining the required guarantees.

Article 431

- In case either during the occupation or after the expiration of the fifteen years referred to above the Reparation Commission finds that Germany refuses to observe the whole or part of her obligations under the present Treaty with regard to reparation, the whole or part of the areas specified in Article 429 will be reoccupied immediately by the Allied and Associated forces.

- If before the expiration of the period of fifteen years Germany complies with all the undertakings resulting from the present Treaty, the occupying forces will be withdrawn immediately.

The occupation clause massively offended German sensibilities, but it was just under the circumstances. Germany's own terms it dictated to the Russians in 1917 had been massively more harsh and Germany had shown a pronounced aggressive territory apatite.* A fifteen year occupation (until 1934) was designed to give the Allies space to defend against renewed German hostility and a defensive position on the banks of the Rhine while it was hoped a newly democratic Germany might join the democratic family of nations, a hope that would ultimately fail.**

The occupation did not go smoothly. The United States Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and the war against Germany was technically brought to and end in 1920 by declaring the war at an end. The U.S. participated in the occupation but brought almost all of its combat forces home by December 1919, leaving a force of 16,000 men behind. That force, in the context of American history, was not inconsequential but it was also partially administrative and also partially engaged in efforts to locate American graves left behind by the fighting.*** The British, the other major non continental power, went from eleven divisions as originally formed in 1919 to just over 13,000 men by 1920.****

In 1923 Warren G. Harding ordered the return of the remaining American soldiers, pulling the U.S. out of Europe entirely. French and British soldiers remained, and in fact British soldiers had been called upon by the German government to put down Red revolutionaries, something that reflected the desperate condition the German government was in and the British willingness to prolong its fighting engagements, as it had done in Russia. That same year the French occupied the Ruhr, which they were allowed to do under the Treaty of Versailles, in response to the German governments default on repatriation payments. The French remained until 1925 in a move that proved to be highly unpopular to the Germans, but which (while this is contrary to the normal view), was likely justified under the circumstances.

The Allied occupation of the Rhineland concluded earlier than the Treaty of Versailles called for as under the subsequent Locarno Treated the time had been shortened until 1930. That subsequent treaty was an effort to work towards the repair of German and French relations. Rather obviously, no matter what the goal was, it failed to ultimately achieve that goal.

Much ink has been spilled since 1945 arguing that the Versailles Treaty, including those provisions that allowed for occupation of Germany (and in particular the Ruhr) were far too harsh and responsible for World War Two. In retrospect, however, they weren't harsh enough. Germany had acted barbarously in its behavior and goals in World War One and yet in spite of that, the Allies chose to call the fighting off before they'd entered German soil. In November 1918 the Allies were advancing at a rapid pace and open field warfare had returned. It was known to the Allies that the rank and file of the Germany navy had revolved against the Crown and the Germany navy was not only a nullity, but a new armed internal force against the German government which the German government was not only having to call upon its army to suppress, but which was becoming successful in recruiting rebellious soldiers against the government as well. Austro Hungaria was disintegrating and no longer remained any sort of support to Germany at all. The Allies were planning for a war that would go into the spring and summer of 1919 and result in a complete German defeat. Their error was in thinking it would take that long. While the Germans were still fighting in November 1918, there's very little reason to think that they would have been doing so in December 1918, or January 1919. Had the Allies refused German entreaties for an armistace, the Allies would have entered a Germany aflame in revolution in the winter of 1919. While that would not have been pleasant, the result would have been a complete and total German defeat.

By agreeing to enter into an armistice when they did, the Allies acquiesced to two late state German war aims; 1) the German state, such as it was, was preserved over a country that, while in revolution, still existed; and 2) the Prussianized German Imperial Army continued to exist uninterrupted. Both of those goals would suffer some modification due to the Versailles Treaty, showing how weak the Imperial Army had become, in that its size was severely limited (and the Navy was likewise controlled), and Germany had to give up Posen and part of Prussia to Poland. Be that as it may, most of Germany never had an Allied soldier set foot on its ground, the German army continued to exist with a straight de facto lineage back to early Prussian times, and the Germans could credibly maintain that they hadn't been fully defeated. Maintaining that maintained a fiction, the Allies had saved Germany from total defeat as a desire to end the bloodshed was so strong that they were willing to give up complete victory for an early end of the war even if that meant preservation of a German state with a Prussianized German army.

Allied zones of occupation after World War Two.

That lesson was so strong for the Germans that in formulated their efforts late in World War Two. Historians have often wondered why Germany kept on fighting after its defeat was so apparent in the Second World War. But taking into account that World War Two was only about twenty years distant from World War One, and that the German Army of World War Two retained many senior officers who had been in the German Imperial Army, there was every reason for the German military leadership to suppose that the Western Allies at least would agree to a negotiated peace to end the bloodshed early a second time. Indeed, there was pretty good reason for them to suppose that the Western Allies, and maybe the Soviets as well, would entertain a repeat of the negotiations that brought the fighting to an end in 1918, meaning that if the German military deposed the Nazis, as they had effectively done with the Kaiser, surely the Allies would negotiate in a fashion that would leave the army and country intact. That hope proved delusional as the Allies had learned their lesson the second go around.

Nonetheless its important to note that the apologist for Imperial Germany who maintain that the horrors of World War Two were brought about because of the defeat of Imperial Germany in the Great War, or alternatively because of the "harsh" peace imposed upon the Germans to end that war, really miss the point entirely. It's true, of course, that Imperial Germany did not engage in anti Jewish genocide in 1914-1918, but Germany's actions in the East certainly fit well as a prelude to what happened in the Second war and at least Ludendorff was open about his desires to depopulate regions of the East and resettle them with Germans. And in France and Belgium the Germans in fact acted with barbarism. By 1914, when the war commenced, and indeed much earlier dating back to the late 19th Century, the seeds of totalitarianism were already well planted in the soil of autocratic monarchies and struggling to burst forth. It's no accident that the three most autocratic European imperial states, Russia, Austro Hungaria, and Germany all saw communist revolutions following the war and that their fragile democracies collapsed. Had Imperial Germany been victorious in 1914 and acted in accordance with the desires of its monarch and military, there's plenty of room to suppose that its' history would have at least followed that of Imperial Japans, whose monarchy was effectively deposed and controlled by its military following World War One.

Looked at realistically, therefore, the real act of failure was that the Allies did not, in the fall of 1918, inform Germany that the end had come and there was no hope for anything other than a complete surrender. That would not have occurred, however, in no small part due to Allied fatigue and the unrealistic hopes of Woodrow Wilson. So that is retrospectively hoping for too much, most likely. If that had occurred, however, a more democratic Germany may have survived, or alternatively a series of German states which would have been prevented from combining. Beyond that, the second act of failure was not acting more aggressively to bring that sort of goal about in the treaty that brought a formal end to the war.

________________________________________________________________________________

*Those who argue the treaty was too harsh seemingly forget Germany's behavior during the war, and in particular its behavior late war in the East. They likewise seemingly forget that Imperial Germany had come about by uniting the various German independent states under the Prussian Crown following the Franco Prussian War even though the Prussian Crown had expressly rejected taking a constitutional position over a united Germany as a result of the 1848 revolutions.

**Hence the large zones for Belgium and France, both of which had been directly invaded in 1914 and, for France, also in 1870. The small British zone simply kept them in the game. The big American one reflected its large late war contribution.

***Americans had traditionally made poor occupation troops in general except in Central America, where professional forces in the form of Navy and Marine detachments had been used in that fashion. The Army's prior experiences were limited to the Mexican War, the post Civil War American South, and the Philippines, none of which had gone very well.

Moreover, while all of the occupation troops were largely conscripts, the view of the average American didn't suit their being occupation troops very well. This is perhaps reflected by a report of a Savannah Georgia newspaper from June 1919, at which time Georgia National Guardsmen who had served in the army of occupation were returning to Georgia. That reported noted that they were returning with a significant number of German brides a large number of whom were pregnant, indicating that the marriages, or at least the relationship, had a bit of a history. Keeping in mind that southern Germany was largely Catholic it would be reasonable to assume that the pregnancies were almost all post marriage which means that the relationships with American troops had started nearly as soon as the Army had entered Germany. Friendly relations between Germans and Americans were such a problem that American commanders were issuing orders trying to prevent it nearly immediately while at the same time Germany villages started to incorporate occupying Americans servicemen into significant village events, such as the celebration of Christmas. While its' popular to note that the Germans did not take to the occupation well, it's also important to note that much of the hostility to the occupation was actually outside of it.

****While the United Kingdom had a pronounced colonial history it had traditionally had a very small standing army and it also had to rely upon conscripted soldiers in the war. The UK began to repatriate combat troops almost instantly when the armistice was signed and like the United States its troops were poorly suited for occupation duty. Additionally, the UK had large overseas commitments it retained and it went right into a domestic revolution of its own in Ireland. Finally, a lot of "British" troops were in fact Canadian, New Zealanders, and Australians, none of whom were going to be willing or able to stay for a long occupation.