Smell!

WHY is it that the poet tells; So little of the sense of smell?These are the odors I love well:

The smell of coffee freshly ground;Or rich plum pudding, holly crowned;Or onions fried and deeply browned.

The fragrance of a fumy pipe;The smell of apples, newly ripe;And printer's ink on leaden type.

Woods by moonlight in September Breathe most sweet, and I remember Many a smoky camp-fire ember.

Camphor, turpentine, and tea,The balsam of a Christmas tree,These are whiffs of gramarye. . .

A ship smells best of all to me!Christopher Moreley

Just the other day here I did a post on coal stoves, which was inspired by a post on the A Hundred Years Ago blog. In that post, I mentioned the smell of burning coal and became diverted on the topics of routine smells of the past. I noted there.

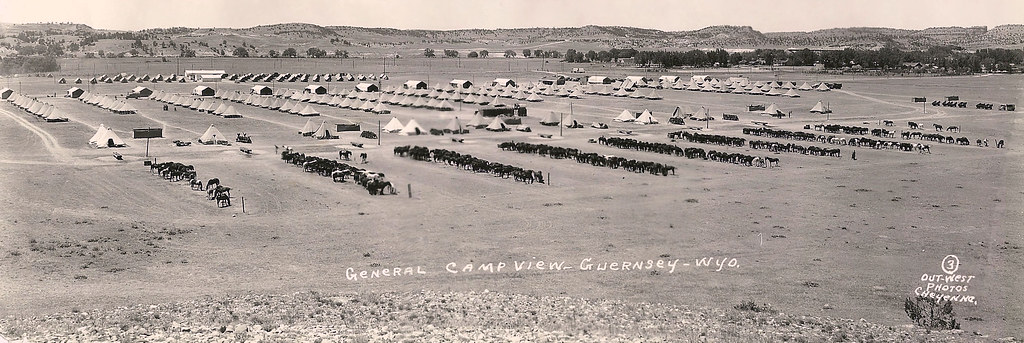

Which brings up this odd point. When we read about the history of something, we usually appreciate the sense of sight much more than anything else, as we have a "mind's eye". We don't have a "mind's smell", and while extraordinary smells are noted in fiction and history, its only when they're extraordinary. We are much more likely to have something described to us as to what it looked like than anything else, as that's principally how we perceive the world. We might get in what people heard as well in a description, particularly if its speech, but only rarely do we read as to what something smelled like. You can read, for instance, volumes and volumes of Westerns that contain a line about what horses in a corral look like, but as anyone who has been around such scenes in real life knows, there's a distinct smell that goes with that.

And indeed the entire world was full of smells a century ago that most of us don't even imagine today. I'd argue that the average person encountered many more smells on a daily basis, no matter where they lived or what they did, than they do now. Today, I'll get up, shave at some point, and go to work. In the course of doing that, I'm going to smell the coffee I make, smell the shaving cream I use, and maybe smell a little bit of fuel my motor vehicle burns on the way to work. I probably won't encounter any distinct smells until somebody makes lunch at work, if somebody does, and then again until I come home and smell dinner cooking, or maybe the grill on. Pretty minimal.

But if I lived a century ago, there'd be a lot more. The stoves used for cooking gave off wood, and now I know coal, smells. Coffee still smelled. Lunch time meals had more smells. Horses in the street had their own smells, to which was added the smell of horse urine and horse flop. In big cities, in tenement districts, people kept chickens and livestock, which definitely have a smell. Washing was more difficult so clothing was more likely to have a smell. Men didn't use deodorant at the time and therefore for men in the workplace, and that was mostly men, they had a smell. Women of course would as well, but chances are that women were more likely to use perfume to cover their smells, which was its principal original purpose, and that stuff has a (horrible, in my opinion) smell. Men smoked in large numbers and women were just starting too, and that certainly has a smell.

I won't argue that we now have a poverty of smells. But the world, mid 20th Century, certainly had a lot more smells.

And among those smells were smoke. And some of that smoke was from coal fired stoves.

I'm going to expand on that a little bit. I.e., what did the world smell like to an average person, on an average day?

Well, it wouldn't be too much to say that it smelled a lot.

That may sound like an odd question, but it would have been significantly different than it is now.

On an average day now, I get up and make coffee. Indeed, the days which I don't have coffee in an average year vary from less than five to zero. I drink coffee. but only at home. I.e,. I don't drink it at the office.

Coffee has a distinct, and pleasant, smell.

Most days if I eat breakfast, which I don't always, it's just cereal. Cereal doesn't have much of a smell if any at all. Sooner or later I shave, and that means I use a scented shaving products as its all scented. I get dressed and go to work. As I can't stand the perfume that goes into laundry soap, my clothes don't smell like that.

I generally drive to work, although sometimes I ride my bike. If I bike, I encounter other smells than I might if I drive, although recently the top has been off my Jeep so I am catching scents coming and going, including the scents of the two flattened skunks that are down the highway. When I drive the Jeep, I also catch a lot of vehicle odors, which people inside other vehicles don't. I.e., I smell their exhaust, sometimes their burning brakes, burning oil, and the cigarettes that smokers open their windows to vent.

At work there are really no noticeable smells except the coffee made early in the day and then whatever people heat up in the microwave for lunch. Microwaved meals have a smell, of course. I once had a paralegal that intentionally burned oatmeal for breakfast every day which raised two questions; 1) why would a person like burnt oatmeal and 2) why didn't she eat on her own time? Another paralegal I had was on a weird diet that entailed heating boiled eggs in vinegar which, I assure you, stinks.

Sometimes I catch some distinct smells in the elevator during the day. Years ago I had a paralegal who wore copious amounts of perfume, which I can't stand, and you could definitely smell that. An old lawyer on another floor smoked cigarettes constantly, including the elevator, and you could smell that. When I first practiced law we allowed some people to smoke in their offices, where as now people have to go outside of the building to smoke, and of course that smell. One lawyer who worked for us years ago smoked cigars if he was close to trial for, I guess, stress relief, and cigars have a distinct odor.

When I leave the building at noon I catch the smell of the Mexican kitchen the restaurant across the street and the Chinese kitchen in the restaurant around the block. On the way home at the end of the day I can catch the smells of barbeques that have been heated up for summertime evening meals.

All pretty routine.

What if it was when we started this blog off, around 1910? Or what about later, around 1920?

If it were 1910, or 20, and in the summer, or for that matter the winter, the first thing that would happen would be a stove would be stoked. No stove, no coffee. I've imagined most stoves were wood fired, but I've found out in the last few days, I'm wrong. They were coal fired. Indeed, I now have to go back and correct something I wrote in my slow moving novel.

So, the first thing I do on any day would be to fire a stove with coal in order to make coffee. That would take some time.

And then I'd make coffee. And making that sort of coffee involves boiling coffee.

Portable gas camp stove. The coffee pot on the left is being used to boil coffee the old fashioned way. Ground coffee dumped in the pot and boiled.

This process would have taken some time. Fortunately for me, I'm a really early riser, so that would not have been a problem. This would have left the stove warm enough for anyone who wanted a cooked breakfast, which I doubt would have been me. Cereal was already around at the time and I could see myself having been an early adopter of it. If I did cook something, it would probably be oatmeal, which my mother called porridge (it took me a long time to realize that they are normally the same thing in most households), when she referred to it from her youth. She didn't like it.

World War One vintage advertisement boosting cereals for breakfast.

I have the sense that her mother, or prior to the Great Depression really setting in, her parents domestic help (they lost all of their money in this time period) made porridge for the family and in large quantities. This is what you ate for breakfast and that was your option. . . period. This would have been real oatmeal, not quick oats.

Quick oats were introduced in 1922, so they were around when my mother was a kid, but that's not what they had. They had real oatmeal. I like real oatmeal, but I have the sense that my grandmother was a poor cook and my mother certain was. I think my grandmother likely just boiled up a big batch of oatmeal and you ate it before you headed off to school in the morning, no matter when that was.

My father, on the other hand, never spoke of what they ate for breakfast, so I have no idea. I wish I would have asked him. He always drank a cup, just one, of coffee and it was always instant coffee. He always had cereal for breakfast. These were probably habits acquired early in life, and maybe that says something about what they ate in his parents homes.

My mother, when I was young, often tried to make breakfast which probably also reflects, to at least some degree, what the habit had been at home. I've mentioned the oatmeal but she also made pancakes. They were generally awful. Scrambled eggs was a favorite of hers as well, and she was fairly good at that and favored it herself her entire life. She never ate oatmeal.

Anyhow, after breakfast most people walked to work. Not too many drove a century ago, although if we take the later part of my time frame, that was changing.

Walking, like riding a bike, puts you out in the air where you smell a lot of smells. In the 10s and the 20s, prior to air-conditioning resulting in houses being all sealed up, that would have meant the cooking and stove smells of the houses you passed. Indeed, the entire town would have smelled, to some degree, like coal smoke.

This town would have also smelled like an oil refinery, and when I was a kid in the 60s and 70s, it did. When I was a kid the town had three oil refineries. Now it has one. Two out of those three, however, were downwind from the town, and the only remaining one is. We never smell it.

Midwest Refinery, which became the Standard Oil Refinery, in Casper Wyoming shortly before its massive World War One expansion.

At the time, people would state that the smell was "the smell of money". The upwind refinery was the largest of the three, but even then it wasn't anywhere near as large as it had once been.

I note this not as a criticism of anything, but rather to note something that would have have been common in all sorts of places. Indeed, in the 1910s and 1920s the town would have had three refineries and a stockyard which my family later owned. Most of those were all downwind of the town but they were there and they would contribute to the atmosphere, so to speak, as well as to employment.

For that matter, Cheyenne has a refinery and did at the time. It also had stockyards and a huge population of military horses. Laramie also had stockyards and, yes, at that time a refinery.

Cooking smells, industrial smells and heating smells permeated every town and city everywhere. And in the 1910 to 1920 period, the smell of animal waste was still a factor in daily life as a lot of things were still horse propelled. Automobiles, and automobile smells, were just coming in, but cars and trucks hadn't replaced horses yet.

Union Pacific "Big Boy" locomotive. These massive engines burned coal throughout their service life, never converting to oil like most steam engines.

And the major means of long distance transportation, locomotives, also had smells as at the time trains were all steam engines. Oil fired steam engines had come in for the most part, although coal fired ones still existed, but they were smellier anyway you look at it than diesels, which replaced the steam engines in the 1940s and 50s, were.

If you walk downtown for work you would likely stay there for lunch, and that added, no doubt, to the downtown cooking smells. We still have that, of course, but the town at that time had a lot of bars and restaurants and this helps explain why. There was more need. Office workers didn't have refrigerators in their offices and people who packed a lunch, and no doubt a lot of people did, ate fairly simple lunches. But lots of people simply went out at noon for something to eat, with in most places some of them sitting down in a cafe, which most bars doubled as, and in others people grabbing something from a street vender, which were common at the time. All of that, of course, added to urban smells.

And then late in the day, the walk home.

Exceedingly strange cigar advertisement, circa 1900.

Throughout it all was the smell of cigarettes and cigars, which were a huge item at the time in a way that we've now forgotten, even though that era has only recently passed. Prior to World War One cigars were the dominant tobacco product, but the Great War brought cigarettes in. Smoking, moreover, had been a male thing but now women were taking it up.

And then we have the people.

The people?

Yes. And that brings us to. . . plumbing.

We're so use to water being plumbed into the house that we nearly take it for granted. Indeed, one of the real oddities of Western movies that were made prior to the late 60s, and even on into the 70s, is how clean everyone is all the time. It's like they just took a shower and put on clean clothes.

They hadn't, most of time time.

Indeed, it wasn't until 1885 that a city in the United States had a comprehensive water system, that city being Chicago.

Prior to indoor plumbing, a pretty common practice for a lot of rural families was to bathe once a week. That's actually more than some people like to commonly believe. But it's a lot less than occurs now. Added to that, a lack of indoor plumbing was the norm on American farms and ranches into the 1930s. If that sounds like a long time, a lack of indoor plumbing of some types, including toilets was the norm in rural Italy until the 1960s.

If you lack indoor plumbing taking a bath, and that's what it would be, can really only be accomplished in two ways. One way is in an open body of water of some sort, another is a tub in the house of some sort.

By and large, in the era and society we're speaking of, people didn't wonder down to the river and take a bath once a week. When stuff like that shows up in movies, it's mostly as an excuse to have an odd movie scene. Having said that, in some regions near or what would become the United States this would occur outside of Indian populations, which of course had no other recourse for most of their history to any sort of other method. The notable exception was the Hispanic populations along the Rio Grande. While this falls outside of the area of our focus, we'll note it anyhow as it had an odd influence on American history. In the 1840s, when American troops were first stationed along the Rio Grande, which was disputed territory with Mexico, they would routinely gather on the river to watch Mexican women, more notably young Mexican women, bathe. Mexican authorities on the Mexican side of the river noticed this, and as they also noticed that Catholic troops were crossing the river to avail themselves of Mass on Sunday, it presented opportunities for them to induce desertion in the same way that Hessian troops were similarly induced during the Revolution. . . . free land. . . pretty girls. . . friendly population. . . .

Anyhow. . .

The first hotel in the US to have individual room plumbing was the Tremont in Boston which had that as a feature as early as 1829.

The modern toilet wasn't invented until 1910.

John Kohler, founder of the bath tub. He died in 1900 at age 56, but his company lives on.

Swiss immigrant John Kohler, who worked in his father in law's iron business, got the bright idea of putting feat on a cast iron trough and calling it a "bathtub" in 1883. The idea was a hit and by 1887 most of the company's output was in plumbing items. Home bathing had arrived in a more modern fashion, but it wasn't until 1900 or so that house plans routinely featured indoor plumbing. That shows, in part, that cities and towns had put in water systems by that time, but it also shows that a lot of people were relying upon older methods of bringing water into houses at the turn of hte prior century.

Indeed, it wasn't until the 1920s that new homes routinely featured indoor plumbing including bathrooms with toilets and bathtubs. It'd be a safe bet, however, that from 1900 until 1920, and then on into the 1930s, lots of houses were renovated for indoor plumbing. By World War Two, however, indoor plumbing, including bathtubs were an American norm to such an extent that an entirely new concept of cleanliness existed in the United States, including expectations associated with it.

Indeed, this brings up an odd topic related to what we're discussing here that fits into the time period we're referencing.

"A french girl forming acquaintance with a soldier". Lots of French girls would form such acquaintances during World War One and World War Two, but by and large American troops found France itself primitive and dirty in World War Two where as they did not in World War One. Indeed, quite a few American troops brought home Russian brides from their service in Russia during World War One, where as they same population would have been regarded as hopelessly primitive by World War Two.

During World War One American soldiers were uniformly impressed with the French and romanticized the Italians. Those troops who entered into Germany at the end of the war also were with the Germans, by and large, and to such an extent that American authorities had to take steps to keep American soldiers from getting too friendly with German civilians.

The story is different however, in regard to World War Two. During World War Two Americans were glad to liberate the French but, both as to the rural French and the Italians, they were shocked by how "dirty" they were. This is extremely common in regard with the Italians, whom by World War Two were regarded as absolutely primitive. The view of the common French civilian wasn't very much different, even though that is rarely recalled today. Both were regarded as very dirty. In contrast, Americans were by and large hugely impressed with German towns and civilians, who were often regarded as "clean like us". The exception were combat troops who had seen a lot of action against the Germans and troops who had participated in the liberation of concentration camps. The latter troops detested the Germans, but not because they were dirty.

The reason this is of note is this. The French and Italians had not become dirty in the twenty years between World War One and World War Two. They just hadn't introduced indoor plumbing at the same rates as Americans had. For Americans, by World War Two, routine, and indeed daily, bathing had become the norm and indoor toiletry also was. For rural Italians this wouldn't become the case until the 1960s. For the French it likely did in the wake of World War Two, but it hadn't before that.*

So basically, what that tells us, is that it wasn't really until just about a century ago that the concept of daily bathing came in, in the U.S. Indeed, it also tells us that in the 1910 to 1920 time frame plenty of people remained on the prior routine of a bath once a week.

Soap making company Jas S. Kirk of Chicago showing a munch of manly French soldiers mass bathing under the watchful eye of an officer. They advertised as being soap and perfume makers and chemists. The connection between the three is an honest one and the soap industry employs a lot of chemists. Indeed, I went to law school with a former soap company chemist whose job had been perfecting perfumes for soaps.

Now, we've already addressed this a little bit, but people have a smell. People walking work will sweat. People doing manual labor of some sort definitely will. People around coal burning stoves will pick up the coal smell, just as people around wood burning stoves will pick up the wood smoke smell. People around horses pick up their smell. And people around clouds of cigarette and cigar smoke pick up that smell.

Now, people are, of course, cognizant of all of that, which is once again part of the reason that women wear perfume. Perfume stinks. Yes, I mean stinks, as in it has a stench. It's stench is just supposed to be less vile than what the wearer would otherwise smell like, or at least be more ladylike.

Cologne advertisement from 1877.

Of course, by the time we're speaking of, and some time prior, men's cologne also existed, but I don't really know how far back. It's a difficult subject to really research, but it appears that men's cologne's go back at least to the 19th Century as do the closely related "after shave" products. The latter had the purpose of being an antiseptic when shaving with straight razors posted a danger for infection, which in barbershops in less hygienic days it did. Cologne however was just designed to cover your smell.

While we haven't researched it, it's probably safe to say that women used perfume a great deal more than men used cologne and, by this point in time, aftershave. Indeed, cologne and aftershave are nearly things of the past now and when I run into them, I'm always surprised. Men wearing something smelly of that type has crossed into the effete, which wasn't the case in stinkier times, but I suspect that most of the time most men, at any point in time, didn't use cologne. Most women probably occasionally used perfume, which in fact was once a common gift for women. Having said that, in an era when the majority of women didn't work outside the home, most of them probably didn't wear it most days either.

In speaking of perfume, of course, we're speaking about applying the smelly stuff directly to oneself, but it's in a lot of soaps.

Commercial soap of the type we are familiar with was, oddly enough, a product of World War One and was a German innovation. That's when detergent type soaps came in and started to replace soaps made of fats and lye, which were the norm before that.

Soapine advertisement from 1900. It used good old fashioned whale fat.

Today, most soaps are detergent based soaps, having followed the German innovation, but not all are. Some eclectic folks still use really old fashioned lye based soaps, and one really old soap brand, Ivory, is still around. I like Ivory as its devoid of perfumes.

Ivory soap ad from 1898. It's been the same since 1879.

Soaps like Ivory don't have a noticeable smell, which is one of the things that are nice about them. But the norm with commercial soaps is to add perfume to them. We don't even notice it unless we're sensitive to perfumes (and I am). Lye soap, on the other hand, has a definite smell to it and people who use it alot smell like it.

Something that has a smell, as it is perfumed, are deodorants and antiperspirants. These were not introduced until the 1960s but went on to rapid general acceptance thereafter. Interestingly, I can recall there being a little bit of a negative reaction to it in some quarters, some of which was perhaps prescient. For example, I can recall my father's friend Father Bauer, who shared a common rural Nebraska childhood with my father, commenting on how things were declining and referencing it, looking back on a day, in his recollection, when you could tell that a man at the end of the day had worked a hard honest day by the smell of his sweat.

People would take exception to that now, but there is something to it. Since that time we've gone from one male grooming product to another, to the point where it's really fairly effete and absurd.

We've been talking, of course, about personal hygiene, but part of that story involves washing clothing. We've douched on this before, but not in depth. It was part of our examination on how domestic machinery revolutionized work for women, and therefore we really did't need to look at it much beyond that. Suffice it to say, clothes washing was incredibly laborious work, and it mostly fell to women. We noted there, in part:

So I'm covering old ground here, but a century ago, "steam laundries" were a big deal as they had hot water and steam. You could create that in your own home, of course, but it was a chore. A chore, I might note, that many women (and it was mostly women) endured routinely, but many people, for various reasons, made use of steam laundries when they could.

Women working in a commercial laundry. Laundry workers were often female or, oddly enough, Chinese immigrants.

Working in a laundry, we'd note, was hard grueling work, but it was also one of the few jobs open to women, all lower class economically women, at the time.

Laundry workers and suffragettes marching, 1914.

Of course, women, and again it was mostly women, did do laundry at home as well, which was also hard, grueling, work.

Pearline, a laundry soap, advertisement from the 1910s which urged parents to "train up" children to use it.

In short, washing clothes, as we've dealt with elsewhere in other contexts, was a pain. That meant you washed less often, quite frankly.

That might not have been that big of a deal, particularly if you could take your clothes to the steam laundry, if you had a lot of clothes, but people didn't.

Washing machines are a really recent domestic machine. They're so common now that we don't even think of them, but the electric washing machine wasn't patented unil 1904. Before that, people were washing at home, but by hand. Sales of electric washing machines exploded in the 1920s and remained strong, if reduced, during the Great Depression. And no wonder. As we've noted, they had an impact not only on domestic work, but what people wore.

For our discussion, this matters as it it related to, once again, smell. People had fewer changes of clothes and washing them was hard. Outerwear, like wool coats and vest worn daily, were rarely cleaned. Shirts, socks and undergarments were. In that context, celluloid collars, which seem so strange to us today, made sense. Collars on white shirts really stain. They really, really stain if you wear the same shirt for several days in a row. Detachable collars could easily be scrubbed clean and if you had several collars you could wear the shirt for several days, with coat over it as was typically the case, longer.

"Wash Days" were a common feature of domestic life, with that typically being a week day. That weekly "wash day" is still pretty common, but it doesn't mean what it once did. The scrubbing and hard work, followed by hanging things on a line, or perhaps a rack, aren't at all what they once were.

So what does this leave us with?

Well, clearly, there were a lot more smells to encounter in 1910, or 1920, than there are now. But, by the same token, we hardly notice most of the smells we encounter now. If we were transported back in time a century, we'd notice the smells immediately, as they'd be so strong, and out of our daily experience, today. But did they then?

Probably not.