Ostensibly exploring the practice of law before the internet. Heck, before good highways for that matter.

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

Queen Elizabeth II in Canada

This is a young Queen Elizabeth II in Canada, but what else does it depict? I frankly don't know. Its a photo from my mother's collection, and unfortunately, I no longer know the story behind it.

Does anyone stopping in here know?

Labels:

1950s,

Canada,

Korean War,

Personalities,

United Kingdom

Location:

Canada

Monday, July 30, 2012

The Wyoming Wave

As an initial disclaimer, let me note that I'm a Wyoming native, and that I started driving at a young age. I owned my first care when I was 15 years old, before I actually had a driver's license.

Now, with that out of the way, I'm going to criticize the driving I've been seeing around here recently.

For some reason, a fairly high percentage of Wyoming drivers, in spite of having presumably passed the driving test and thereby being allowed to be the holder of a driver's license, are ignorant of the rules of the road. And by that, I mean they're unaware of the laws that pertain to driving. Not just the speed limit, which people are aware of, of course, but often ignore, but the simple rules of driving.

Let me provide this example.

Almost ever day I have to come to an intersection where I turn on to a state highway. When I do that, I enter the intersection from the west and turn north, so that I'm crossing against an oncoming lane of travel.

About 40% of the time, there will be another vehicle arrive, from the opposite direction, that also needs to turn north. As traffic has not allowed me to turn on, both I, and the other driver, will be waiting at the intersection for traffic to clear.

Under this scenario, the vehicle that does not have to turn into traffic, and which does not have to turn across the other stopped vehicle, has the right of way. No matter, by my observation at least 60% of local drivers, if not more, believe that the first driver to arrive at the road has the right of way. If that's the vehicle crossing the other stopped river, that driver will charge out and take the right of way. Very frequently, moreover, the vehicle that does not have to cross against the other driver, but which arrived second, will sit there, refusing to move.

That takes me to the topic of this entry, the Wyoming Wave. In addition to not knowing the rules of the road, a large percentage of Wyoming drivers believe that the rules can be completely suspended by simply waiving to the other driver. That is, the driver with the right of way will waive to the other driver, and believe that solves it all. Sort of a "come on, . . . cross my lane of travel. . . I won't use my right of way. . ."

This practice is amazingly common, and doesn't apply simply to stops (although it is very common there). I've seen it extremely frequently at four way stops, where a lack of knowledge on what to do is very common, and nervous drivers try to address more than one vehicle at an intersection at a time by doing it. I've also seen the drivers of slow moving vehicles do it in no passing zones, which certainly doesn't make passing any safer.

Indeed, I've experienced it twice today. The first time in the first scenario I presented today. I came up to the state highway and had to wait for traffic. A vehicle coming from the other direction did as I was waiting. We both were turning to the north, with my turn in front of him. No matter, he sat there and then gave me the waive. Ultimately he went when I didn't. And then it happened when I arrived at work. I was set to jaywalk across the street, which I shouldn't be doing, but as I was waiting there a car simply stopped in the street, as if there was a crossing, which encourages me to go into traffic, when nobody else will necessarily stop.

I thought perhaps my observations here were somewhat unique, but just the other day a client came in who lives in a smaller town in this county and commented, without prompting, that the driving in this city was "terrible". It's funny, in a way, to note that, as at one time it was very common here to criticize Colorado's drivers, although I rarely hear that done anymore. Given the widespread disregard for the traffic rules here, we'd be on thin ice now if we did.

Labels:

Automobiles,

Commentary,

Transportation,

trends,

Wyoming

Saturday, July 28, 2012

Smoke in the Air

This has been a summer of constant fires here. Grass fires and forest fires. I've never seen another summer like it, and I've seen some bad ones.

As part of this, there's been smoke in the air here for so long, it's now part of the regular background smell. Normally, most years, that'd alarm me, but this year its normal. This morning, for example, there's a fairly prominent "camp fire" small, of the type that'd alarm me usually. Not this year.

That caused me to ponder, in keeping with the theme of this blog, if things like this were the norm in prior decades. In the mid 20th Century the US began a dedicated effort to fight all forest fires, but prior to that, it didn't do that, and nobody could have. For that matter, as late as the late 19th Century some Indian tribes still set fire to remote forests in order drive game out of them. A good account of one such event is given in Theodore Roosevelt's account of hunting in the Rocky Mountain West, and this would have been in the 1880s or 1890s. As late as the 1940s and 1950s here, sheepmen set fire to the high mountain sagebrush grounds on their way out, knowing that they'd scorch and green grass would come up the next spring, which they were more interested in than sagebrush. Now, of course, that'd be a crime.

Anyhow, I wonder to what extent summers were simply smokey in the past?

As part of this, there's been smoke in the air here for so long, it's now part of the regular background smell. Normally, most years, that'd alarm me, but this year its normal. This morning, for example, there's a fairly prominent "camp fire" small, of the type that'd alarm me usually. Not this year.

That caused me to ponder, in keeping with the theme of this blog, if things like this were the norm in prior decades. In the mid 20th Century the US began a dedicated effort to fight all forest fires, but prior to that, it didn't do that, and nobody could have. For that matter, as late as the late 19th Century some Indian tribes still set fire to remote forests in order drive game out of them. A good account of one such event is given in Theodore Roosevelt's account of hunting in the Rocky Mountain West, and this would have been in the 1880s or 1890s. As late as the 1940s and 1950s here, sheepmen set fire to the high mountain sagebrush grounds on their way out, knowing that they'd scorch and green grass would come up the next spring, which they were more interested in than sagebrush. Now, of course, that'd be a crime.

Anyhow, I wonder to what extent summers were simply smokey in the past?

Labels:

Agriculture,

hunting,

nature,

trends,

Wyoming

Downward Mobility A Modern Economic Reality : NPR

I suppose this is related to the recent series of posts I have put up on economic issues, but recently NPR ran this interesting interview on Downward Mobility:

Downward Mobility A Modern Economic Reality : NPR

This is, undoubtedly, both real, and scary. But what struck me to some degree, and the reason I'm posting it here, is that it somewhat taps into the phenomenon of rising economic expectations of the last 30 or so years. I don't know if this is good or bad, but it simply is the case.

By this, one of the things I noted on this interview is that part of the "downward mobility" adjustments some of these people expressed is that they'll not be able to roll their houses over as soon as they like, and buy bigger ones. There's simply a built in expectation that they'd do that, and frankly a lot of people do have that built in expectation.

People have been doing that for decades, so that's nothing new, but there was up until relatively recently much less of an expectation that a person could do that. My parents never did. They bought their house in 1958, after they'd been married a short while, and my mother still owns the same house. Plenty of families of that generation moved once, as their family's grew, but they moved because their families grew, more often than not. Some people did buy a different house in later years, but many did not. A person I worked with for many years related to me that when first married he lived in his parents house, which he shortly thereafter inherited, and would have lived at that location thereafter, but his wife did not want to. They had a house built, where both of them lived until they passed on. The idea of buying another house just because seems much more common now. Or perhaps the ability to do that is much more common.

Another thing I noted is that there's a certain level of economic expectation that would seem to be unrealistic with some of the occupations noted in the interview. This is scary, as its becoming increasingly common all over, but its a bit surprising that some people had high economic expectations associated with certain occupations to start with . I recently noted the same last year during the Occupy Wall Street protests when one protester was holding up something with noting a high student loan debt, with the caption noting that the person was an art major. Majoring in art is fine, but expecting to be able to pay off a student loan of any substantial size with that degree is nearly delusional.

Of course, there was a time when nearly any college degree did in fact mean that a person was guaranteed business employment, if they wanted it, but that day is long over. College degrees are much more common now, and while they're not worthless by any means, they do not have the automatic value they once did. Some of course retain real clout, in terms of economic expectations, but many do not. Even traditional standbys in these regards, like the JD, no longer is a guarantee of that at all, as many recent law school grads in many parts of the country haven't been able to find work at all. All part of the same story, I suppose.

Downward Mobility A Modern Economic Reality : NPR

This is, undoubtedly, both real, and scary. But what struck me to some degree, and the reason I'm posting it here, is that it somewhat taps into the phenomenon of rising economic expectations of the last 30 or so years. I don't know if this is good or bad, but it simply is the case.

By this, one of the things I noted on this interview is that part of the "downward mobility" adjustments some of these people expressed is that they'll not be able to roll their houses over as soon as they like, and buy bigger ones. There's simply a built in expectation that they'd do that, and frankly a lot of people do have that built in expectation.

People have been doing that for decades, so that's nothing new, but there was up until relatively recently much less of an expectation that a person could do that. My parents never did. They bought their house in 1958, after they'd been married a short while, and my mother still owns the same house. Plenty of families of that generation moved once, as their family's grew, but they moved because their families grew, more often than not. Some people did buy a different house in later years, but many did not. A person I worked with for many years related to me that when first married he lived in his parents house, which he shortly thereafter inherited, and would have lived at that location thereafter, but his wife did not want to. They had a house built, where both of them lived until they passed on. The idea of buying another house just because seems much more common now. Or perhaps the ability to do that is much more common.

Another thing I noted is that there's a certain level of economic expectation that would seem to be unrealistic with some of the occupations noted in the interview. This is scary, as its becoming increasingly common all over, but its a bit surprising that some people had high economic expectations associated with certain occupations to start with . I recently noted the same last year during the Occupy Wall Street protests when one protester was holding up something with noting a high student loan debt, with the caption noting that the person was an art major. Majoring in art is fine, but expecting to be able to pay off a student loan of any substantial size with that degree is nearly delusional.

Of course, there was a time when nearly any college degree did in fact mean that a person was guaranteed business employment, if they wanted it, but that day is long over. College degrees are much more common now, and while they're not worthless by any means, they do not have the automatic value they once did. Some of course retain real clout, in terms of economic expectations, but many do not. Even traditional standbys in these regards, like the JD, no longer is a guarantee of that at all, as many recent law school grads in many parts of the country haven't been able to find work at all. All part of the same story, I suppose.

Labels:

Commentary,

Commercial life,

The Practice of Law,

trends,

Work

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

When Only a Human Will Do by Froma Harrop on Creators.com - A Syndicate Of Talent

I posted an item on this on Holscher's Hub as well, and I've written on communications here before, but this is an item worth noting again, in terms of treands:

When Only a Human Will Do by Froma Harrop on Creators.com - A Syndicate Of Talent

We're all used now to listening to, and responding to, the commands of a telephonic machine. That is, we call places, and go through the routine. Perhaps we're not thrilled with it, but we do it. You know the drill: "If you have a question about X, press 4, and state your name". . . and so on.

What an enormous change in expectations.

In some parts of the country people still spoke with telephone operators at the telephone exchange simply to place a call in to the 1950s. You could always get an operator by dialing 0, and sometimes ask questions about the call you just had. I haven't tried to get an operator for years, but I suspect it'd be automated now. And nobody calls an operator to place a long distance call. Shoot, I wonder how difficult it would be to even fine an operator if you wanted to.

And I don't know that many of our predecessors of a few decades back would have tolerated a call that only involved responding to machines, which is just what I did this morning in order to determine the answer to a government payment question on a mater I was working on.

Most folks don't like this change much, and I don't frankly either. It's always a relief when you get to speak to an actual human being.

When Only a Human Will Do by Froma Harrop on Creators.com - A Syndicate Of Talent

We're all used now to listening to, and responding to, the commands of a telephonic machine. That is, we call places, and go through the routine. Perhaps we're not thrilled with it, but we do it. You know the drill: "If you have a question about X, press 4, and state your name". . . and so on.

What an enormous change in expectations.

In some parts of the country people still spoke with telephone operators at the telephone exchange simply to place a call in to the 1950s. You could always get an operator by dialing 0, and sometimes ask questions about the call you just had. I haven't tried to get an operator for years, but I suspect it'd be automated now. And nobody calls an operator to place a long distance call. Shoot, I wonder how difficult it would be to even fine an operator if you wanted to.

And I don't know that many of our predecessors of a few decades back would have tolerated a call that only involved responding to machines, which is just what I did this morning in order to determine the answer to a government payment question on a mater I was working on.

Most folks don't like this change much, and I don't frankly either. It's always a relief when you get to speak to an actual human being.

Labels:

Commentary,

Communications,

trends

The high tech alternative to horses. . . . the bicycle

It's strange to think of it now, but at the turn of the prior century it wasn't the automobile that was seen as the modern alternative to the horse, but the bicycle.

Bicycles were all the rage. They took cities by storm as average people saw them as a cheap to buy, cheap to maintain, alternative to walking, or in some cases riding, that didn't require any feed. Their advance was so extensive that they were even adopted by Armies, with even the U.S. Army trying them out in the West. Indeed, probably to the surprise of most modern Americans, some European armies, including the German Army, continued to use bicycles for some troops up to and through World War Two. The Swiss Army still has bicycle using units, and the U.S. Army has very recently experimented with a bike that can fold up into a small portable size.

The early bikes compared very favorably with the automobile too. They were not a great deal slower and they were much, much, cheaper to own. And they were much quicker than walking, which is actually how most town and city people got around. Contrary to the popular imagination, while there were thousands of horses in the cities, most average city and town dwellers did not ride, and did not own a horse. They walked. Bikes, therefore, looked pretty good.

All things being equal, a visionary of 1900 would have had every reason to look forward and see a future with lots of bicycles, a few automobiles, and fewer horses.

We've linked in a couple of interesting blog sites this morning dealing with the U.S. Army and bicycles. The Army's experimentation with bikes didn't last long, that go around, but it shows how in vogue they were.

Bicycles were all the rage. They took cities by storm as average people saw them as a cheap to buy, cheap to maintain, alternative to walking, or in some cases riding, that didn't require any feed. Their advance was so extensive that they were even adopted by Armies, with even the U.S. Army trying them out in the West. Indeed, probably to the surprise of most modern Americans, some European armies, including the German Army, continued to use bicycles for some troops up to and through World War Two. The Swiss Army still has bicycle using units, and the U.S. Army has very recently experimented with a bike that can fold up into a small portable size.

The early bikes compared very favorably with the automobile too. They were not a great deal slower and they were much, much, cheaper to own. And they were much quicker than walking, which is actually how most town and city people got around. Contrary to the popular imagination, while there were thousands of horses in the cities, most average city and town dwellers did not ride, and did not own a horse. They walked. Bikes, therefore, looked pretty good.

All things being equal, a visionary of 1900 would have had every reason to look forward and see a future with lots of bicycles, a few automobiles, and fewer horses.

We've linked in a couple of interesting blog sites this morning dealing with the U.S. Army and bicycles. The Army's experimentation with bikes didn't last long, that go around, but it shows how in vogue they were.

Labels:

Animals,

Bicycles,

technology,

Transportation,

trends

The Bicycle Corps in Yellowstone Park

Really neat blog on the U.S. Army's bike corps of the late 19th Century, in Wyoming:

The Bicycle Corps in Yellowstone Park

Serious bicyclist, way ahead of their time.

The Bicycle Corps in Yellowstone Park

Serious bicyclist, way ahead of their time.

Sunday, July 22, 2012

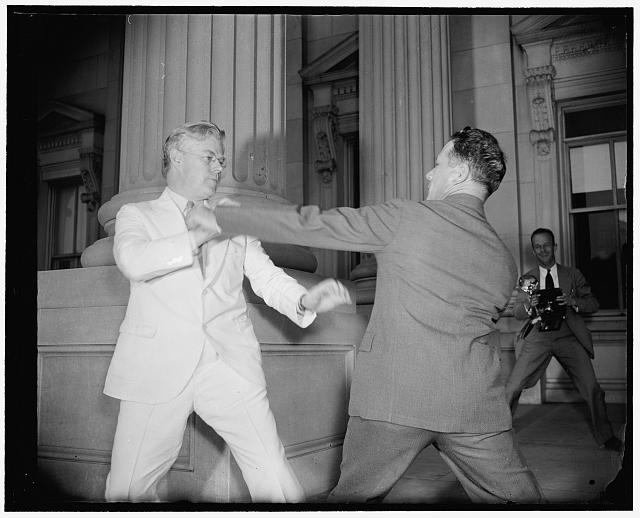

Civility

One of the major things this blog tries to track is cultural changes, or trends. Here's one that I've been able to notice a great deal in my own lifetime. A decline in civility.

Others have noted this, but I think I'm likely defining this a bit more broadly than it usually is. I'd define civility as a conduct not only limited to actions, but also to manners of speech. If that is done, the decline in civility has been enormous.

When I was younger, people were generally fairly careful with their speech. We were taught not to use coarse language of any kind. This included not only swearing, and language which would have been regarded as subject to religious concerns, but simply course language. You did hear it, of course, but not terribly frequently. If you heard it from adults, it was usually because they were in a situation that was extremely stressed. From some adults you never heard course language. I do not recall hearing such language from my mother on more than a single occasion, by which time her mind was failing. If my father ever used such language, it was a sign that he was extremely upset, which was very rare. During my father's entire lifetime, I probably heard such language used less than I hear it from some individuals in a single day, in some circumstances.

There were, of course, people who routinely used very course language, but that tended to be regarded as a sign of a certain character defect in the individual or, in some cases, indicative of a certain employment or cast. That is, you might expect it from soldiers. You didn't expect it from just about anyone else. If you heard it from a manual laborer they were regarded as a person who was unaware of the appropriate standards of conduct. If you heard it from a professional, you placed them in a poor light.

You did tend to hear language of this type from boys in their late teens, which was at a point where they were experimenting with speech. But that was expected to clear up.

Now I'll hear speech of this type all the time. Even professionals can be found using language that was formerly the province of Marine Corps Drill Sergeants. It hasn't been a good trend. For one thing, it seems to have reduced the meaning of such language entirely. For another, it seems to have been part of, even an engine of, a general decline in standards. As civil language had declined, civil conduct has also.

Part of that decline has been reflected in the expansion of suggestive everything. Even 15 years ago a person wouldn't have decorated their vehicles with suggestive or crude stickers. Now I seem them everywhere. Rude t-shirts have also been common, challenging the viewer with provocative or combative suggestions. This just wouldn't have occurred up until about 15 years ago, and certainly not 20 or more years ago. For one thing, chances are high that a young male wouldn't have been able to find a young female would would have been willing to be seen with him if he had a suggestive sticker on his vehicle, or if he wore a t-shirt with a suggestive slogan. Now, however, young women wear t-shirts themselves with suggestive slogans on them.

It'd be easy to blow this off as really meaning nothing, but it does. A culture that loses a sense of propriety on certain conduct will tend to lose a sense of appropriateness as to any behavior at all. That is, if a person doesn't know what language is and is not appropriate, at some point he'll also not know what standards are. And as what was intended to be provocative becomes common, it has the effect of making the behavior common. One of the odd facts of modern life is that there's almost no language left that actually has the ability to shock, so part of speech itself is thereby reduced. This isn't to say that I'm advocating the use of such language in certain situations, but I'm noting that the treat nature of something like Baklava doesn't exist if all you ever get to eat is Baklava.

Expanding this out a bit further, this seems to have infected our political speech to an increasing degree. Not that this is unusual, however. There were once, of course, fist fights on the floors of Congress, and even a caning many decades ago. And some political speech of the 19th Century and early 20th Century is shockingly violent, racist, or just flat out goofy. So, here, we can't really say that this is wholly novel.

None the less, there seems to have been a shift in the last several decade ago where some political speech could be quite extreme and has become very common, and it recently has become very noticeable. I don't mean to suggest, by the way, that one party of the other is to blame here, and I'm not pointing towards any one person. Rather, it just concerns me when debates became sloganeering based on accusations. Having said that, as noted, there's always been some degree of this. Still, when the extreme is used so commonly, as it is here to, at some point people quit listening.

I suppose the point of this entry is mostly to note this trend. But also to note that more restraint in language doesn't hinder speech, it actually enhances it.

Saturday, July 21, 2012

Going To The Dance

The other day, I was at an event which included a dance. The dance was well attended, but a friend of mine mentioned that he'd heard that the dance was once the central event, and no longer was. He further observed that it seemed to him that dances had once been a central event for people, but that era had passed.

I've never thought of that, but I think there's something to it. Not that dances don't occur, I just don't think that dancing is as big of a deal to people now as it once was.

In making this observation, I have to note that I can't dance. But then maybe that forms part of my observation. I never learned how. When I was of that age, it seemed that traditional dancing was not in vogue. There were high school dances, but swing dancing, etc., didn't occur at them. This was also true of the very few dances I attended while in college. The Rock and; Roll era of the 1960s had impacted dancing to the point of almost destroying it, to some degree, so that by the late 1970s and 1980s, my high school and college years, dancing was sort of a free style type of deal. You'd see it, to be sure, at school dances or college bars, but nothing like that depicted above.

And it wasn't as if people said "let's go out dancing" either, or even "let's go to the dance". While at the University of Wyoming I think I went to one actual "dance", a dance at a dormitory that the foreign students association hosted. All the other dancing I saw during the 80s in Laramie was at parties, concerts or bars, and all of it was the descendant of the rock type that became predominant in the 1960s.

But this wasn't always so. As noted above, a friend of mine noted how dancing was once a much more common event, and further commented how, in Western Nebraska, where he was from, people in small towns had frequently "gone to the dance" on weekend evenings, or at least young people do. And I've heard many recollections of that type as well. Indeed, just last night, at a 50th wedding anniversary party I heard a recollection about the "dances in Powder River". Powder River is a small town in western Natrona County, and I bet that there hasn't been a dance held there in decades. Apparently there used to be one darned near every weekend, and I don't doubt that something like that was close to correct.

I will note, on that, that once I started to date my wife, who in fact is from Powder River, that I encountered real dancing for the first time. Rural people in Wyoming all know how to dance, so it's pretty evident that dancing as a social event has hung on in the rural west. And they dance well too. Even today, at wedding receptions of rural couples, real swing dancing is very common, to all types of music. Perhaps, of course, it's coming back in, in general, but I'd be surprised.

I'm not sure what sparked this change, but whatever it is, is part of a bigger trend. A book sometime ago entitled "Bowling Alone" advanced the thesis that Americans more and more engage in solitary activities, rather than getting out with people. While to anyone generation that's hard to perceive, I think it evident that this is true. Probably our hectic lives, and television, and now the computer, all contribute to that. At one time people had to get out, basically, or the only other option was staying at home reading or listening to the radio (after there were radios). Therefore, group activities of any kind, were much more significant than they are now for many, indeed most, people.

I've never thought of that, but I think there's something to it. Not that dances don't occur, I just don't think that dancing is as big of a deal to people now as it once was.

In making this observation, I have to note that I can't dance. But then maybe that forms part of my observation. I never learned how. When I was of that age, it seemed that traditional dancing was not in vogue. There were high school dances, but swing dancing, etc., didn't occur at them. This was also true of the very few dances I attended while in college. The Rock and; Roll era of the 1960s had impacted dancing to the point of almost destroying it, to some degree, so that by the late 1970s and 1980s, my high school and college years, dancing was sort of a free style type of deal. You'd see it, to be sure, at school dances or college bars, but nothing like that depicted above.

And it wasn't as if people said "let's go out dancing" either, or even "let's go to the dance". While at the University of Wyoming I think I went to one actual "dance", a dance at a dormitory that the foreign students association hosted. All the other dancing I saw during the 80s in Laramie was at parties, concerts or bars, and all of it was the descendant of the rock type that became predominant in the 1960s.

But this wasn't always so. As noted above, a friend of mine noted how dancing was once a much more common event, and further commented how, in Western Nebraska, where he was from, people in small towns had frequently "gone to the dance" on weekend evenings, or at least young people do. And I've heard many recollections of that type as well. Indeed, just last night, at a 50th wedding anniversary party I heard a recollection about the "dances in Powder River". Powder River is a small town in western Natrona County, and I bet that there hasn't been a dance held there in decades. Apparently there used to be one darned near every weekend, and I don't doubt that something like that was close to correct.

I will note, on that, that once I started to date my wife, who in fact is from Powder River, that I encountered real dancing for the first time. Rural people in Wyoming all know how to dance, so it's pretty evident that dancing as a social event has hung on in the rural west. And they dance well too. Even today, at wedding receptions of rural couples, real swing dancing is very common, to all types of music. Perhaps, of course, it's coming back in, in general, but I'd be surprised.

I'm not sure what sparked this change, but whatever it is, is part of a bigger trend. A book sometime ago entitled "Bowling Alone" advanced the thesis that Americans more and more engage in solitary activities, rather than getting out with people. While to anyone generation that's hard to perceive, I think it evident that this is true. Probably our hectic lives, and television, and now the computer, all contribute to that. At one time people had to get out, basically, or the only other option was staying at home reading or listening to the radio (after there were radios). Therefore, group activities of any kind, were much more significant than they are now for many, indeed most, people.

Thursday, July 19, 2012

Society of the Military Horse • View topic - Architectural Artifacts of the Equine Era

This recent thread on the Society of the Military Horse forum, entitled: Architectural Artifacts of the Equine Era brings up some interesting items relevant to this site. Artifacts in architecture, etc. that are related to the horse powered era, which in many instances is the recent horse powered era.

Particularly interesting, at the time of the posting of this item here, is the discussion on city and town fountains for horses, an item that never would have occurred to me. Most particularly, it wouldn't have occurred to me that this was sponsored as a charitable effort, but when you think of all the horses in towns and cities (a huge number prior to World War One), it makes senses.

Particularly interesting, at the time of the posting of this item here, is the discussion on city and town fountains for horses, an item that never would have occurred to me. Most particularly, it wouldn't have occurred to me that this was sponsored as a charitable effort, but when you think of all the horses in towns and cities (a huge number prior to World War One), it makes senses.

Labels:

Animals,

The Appearance of Things,

Transportation,

trends

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

History, Jobs, Politics, Exaggeration and Gross Simplification

Normally I wouldn't post an item on modern politics on any of my blogs, but here I'm making an exception. This is probably even more exceptional as I'm posting that item here, on Lex Anteinternet, which is supposed to have a historical focus. Be that as it may, there's some connection with the focus of the blog here, so its not completely off topic, if darned near so.

Recently, while travelling about, I was listening to podcasts of the Sunday morning talk shows. The focus on both Meet The Press and This Week was the economy, with Republican and Democratic spokesmen taking shots at each other about that topic, and more specifically, going after each other on job loss. If you were to listen to the Democrats you'd hear that Mitt Romney is a poor choice for president as, they claim, he's a "corporate raider" whose business practices resulted in jobs being exported overseas. If, on the other hand, you were to listen to the Republicans you'd hear that President Obama is directly responsible for tax policies that are causing jobs to go overseas.

Well, what this really demonstrates is either the poor state of the American public's understanding of long term economics or, perhaps more optimistically, an insulting level of the assumption of the misunderstanding of that topic by both political parties. At any rate, almost nothing about the topic of job flight to other nations is correctly stated, and the vague solutions proposed by both parties operate with a deficit of understanding on that topic.

So, what is the truth of the topic? And what are the solutions, if any? And do we even really want solutions?

Well, to start off with, lets put this in a historical framework. The often repeated claims that the sitting President is wholly responsible for job flight fails to acknowledge that this trend isn't recent, and isn't even close to being recent. It basically started in the 1950s, and in a way that's significant to the current debate.

Prior to the 1950s, the United States was a rising manufacturing power, even in spite of the Great Depression which put a damper on it. By World War One US manufacturing capacity was so vast that the United States could legitimately make the claim of being the Arsenal of Democracy. Starting off with an arms deficit, which it really never made up during the war, the US was nonetheless exporting arms to the Allied Powers during the war. During World War Two this became so much the case that the US manufacturing capacity dwarfed that of any other belligerent. The war itself left the United States the only really intact manufacturing power, which was responsible in large part for the happy times of American manufacturing of the 1950s and 1960s.

World War One vintage poster.

From the late 1940s through the mid 1960s, Japan was associated with bad junk. "Made In Japan" was a joke for really lousy trinket material, but in fairness this was stuff that we'd once made here in the United States. How did that occur?

Well, after Europe was bombed into rubble during World War Two, it really had a diminished manufacturing capacity. We had a vast one, as our factories had expanded during the war. That left us making most of the nifty stuff that we had formerly competed with Europe to make. Not all, of course, but most. In turn, we no longer needed or wanted the really poor paying cheap manufacturing jobs we once did. And, Americans coming out of the war no longer wanted to work those jobs anyhow. So they went to the more desperate, the Japanese, who had a much more primitive economy going into the war, and whose economy had been destroyed by the war. They need the jobs and were happy to take them.

Rural poor in post war Japan, photograph by my father, circa 1954.

Of course, the Japanese were not ignorant as to much more advanced manufacturing, as World War Two had proven, and in the natural order of things, they began to rebuild the economy of Japan and its manufacturing abilities. By the 1960s they were making automobiles, motorcycles, camera equipment, and airplanes that rivaled any we were making. We didn't notice this, however, until the 1970s, when our own economy began to really suffer.

The news and commentary from the 1970s sounded a lot like that now, except that Japan filled in for China in these regards. With the gas crisis of the 1970s coming in, Americans began to turn towards Japanese cars which were well made and fuel efficient. Soon thereafter, it seemed everything was made in Japan. We began to loose sections of the global economy we'd once dominated, and we've never regained our prior footing. We never will either.

But, things being what they are, the predictions that the Japanese would dominate the global economy, and even re-militarize, turned out to be completely false. By the 1980s the Japanese had shot their economic bolt. Basically regaining 40 lost years of economic advancement, they caught up with us, and then joined in with our problems. The Japanese no longer manufactured cheap junk, but quality items. The cheap junk section of the economy had moved to the Asian mainland. It's still there. But. . . a lot of good stuff is coming out of Asia also, which probably means. . . .

Anyhow, what this meant is that a lot of our good manufacturing jobs were competing by the 1970s with the same sectors in Japan. And both the Japanese and the American companies that occupied these positions were not shy about moving manufacturing around to attempt to compete. This began to accelerate in the 1980s.

Added to that, in the 1980s the United States, Canada and Mexico entered into the North American Free Trade treaty, which operated to cause all three North American nations to be one big free trade zone. The reasons for entering into this are varied, but frankly some of them were never really well publicized in the first place. As to Canada and the United States, the union made a great deal of sense, as Canada and the US were one single market anyway. But in the case of Mexico this was simply not true. Mexico still had a lot of state control over sections of its economy, and a large section of the Mexican population was desperately poor. It was this last item that formed part of the unspoken American basis for entering into the treaty.

By the 1970s the US was experiencing a major influx of illegal immigration from Mexico. Illegal entrants came up seeking work that paid better than the very low wages they received in Mexico, or in some cases just to find work at all. NAFTA had the unspoken hope that it would cause the lower paid manufacturing jobs of the US and Canada to emigrate to Mexico and provide some work for Mexicans, which, it was hoped, would in turn result in a boosted Mexican economy long term, as with the earlier example of Japan. This meant, frankly, that US jobs would go to Mexico, which we knew, but we were okay with at the time. Or, rather, the policy makers were okay with it. And indeed, it might have worked. For the first time in its history the majority of Mexicans are in the middle class now, a real achievement. And illegal immigration is slowing down.

All that (i.e., NAFTA) may be fine, but it also is based on a set of fairly false assumptions, in so far as it pertains to the workforce in the United States. The first of those is that these jobs are ones we either do not want, or that Americans will not do. There's ample evidence that Americans will do about any job, and indeed just as these types of jobs are entry level jobs for entire economies, they also may remain entry level jobs for many Americans in depressed areas. Rather, what the truth of the matter is that Americans either will not, or economically cannot, do many of these jobs for the wages employers are willing to pay.

That Americans will work some fairly rough jobs, and low paying jobs, is more than amply demonstrated. There are entire classes of employment which pay relatively low, but for which a person can still get by, and which are sought after. Being in agriculture, I've noted that cowboy is one such job. I've seen quite a few city kids become so enamored with it that they make it a career, even though it pays very little, and there's almost now way to become the owner of the agricultural unit yourself. After a few years you'd think these kids were born on ranches, but they were not, and had no exposure to it at all until they were in their teens. Many other outdoor jobs, such as Park Ranger, Game Warden, Forest Ranger, fit into the same category, as they pay very little, but those who work the jobs love them. Some other jobs, such as teacher, and writer, are similar in these regards.

And Americans will definitely do very hard work if it pays. In this region, hundreds of men are employed on drilling rigs in conditions that involve long hours and dirty hard work. It pays very well, however, so they do it.

What this means is that Americans will do almost any job, either out of love for the job, or money, but they frankly can't work for the very low levels that the exported jobs entail. That brings us back to the main topic.

Contrary to what the Republicans claim, American corporate tax policy is not going to have any effect on the exportation of American jobs overseas. None.; And, contrary to what the Democrats seem to think, businesses do not export jobs overseas for jollies or because they're unpatriotic. It's completely caused by another topic.

Wages and benefits. That's what causes it.

All manufacturing today is in a global economy, and therefore every worker everywhere is competing against every other one. And every business is competing against every other business. A shop making t-shirts in Bangor Maine is competing against those in Bangladesh. That's the reality of it. Tax rates are drop in the bucket in this context. And business often have very little option other than to go overseas or die.

So, that being the case, what can we really do to keep jobs here? And do we really want to.

Answering the second question first, I'd say yes, but we must first concede that many economist argue the opposite. That is, certain economist have argued that a country shouldn't strive to keep the really low level manufacturing jobs (or agricultural jobs for that matter), and that an advanced economy cannot.

I don't agree with that, but beyond simply not agreeing with it, I'd note that the American economy is not as advanced as we like to think. Entire demographic sectors of the American population have never participated in the greater economy, and these are effectively our own third work pockets, I'm sorry to say. Until these sections of the nation have actually risen out of poverty, we remain in the situation of needing the same type of jobs that are going to China presently. So, at least from my point of view, such jobs are necessary.

And, in our modern age, such jobs have proven to be an amazingly rapid path to technological innovation. As things become more and more technological, anything now made has the ability to create a leap of some sort. In some ways, there is no more cheap junk. The trinket maker of today is working in advanced manufacturing tomorrow. Lose any job, and you lose the ability to innovate.

So what can we do. Are the Republicans correct that adjusting the corporate tax rates will bring jobs back home? No. Are the Democrats correct that business men are just big meanies? No. What would have to be done is to basically level the playing field as to wages paid to the employees of our primary global competitors. And that can't be done in a punitive way, which would do little other than to spark some sort of tariff war (which would be a risk of my suggestion below in any event), a move which has always proven to be destructive to the global economy in the past.

Basically, therefore, what you have to do is look at the wage rates and benefits paid to foreign workers, and see what they are and why. If the minimum wage in the United States is $7.25/hour, and it is, and foreign competitors are paying their employees $1.00 day, that's an advantage that foreign workplace has against the American workplace that has to be taken into account. Likewise, if a certain type of job in the US, due to unions or custom, comes with certain benefits that effectively boost what the employee makes in real terms, on an hourly basis, that has to be taken into account. And if there are laws that really impact the cost of an item, such as workplace safety or environmental laws, that should be taken into account. And that can be taken into account in the form of a tariff seeking to simply level the playing field.

So, by way of an example, if a U.S. manufacture finds that raw price of a widget's materials is $5.00, but the cost of labor and law compliance adds $10.00 to it in the US, but only $1.00 to it in China, what we have is a $9.00 difference based solely on external fictional factors. So, taxing the widget $9.00 levels the playing field. If there are other advantages to manufacturing in China after that, whatever they would be, they still will. If they will not, they won't. And if there is an advantage to manufacturing in China, the tariff rate would mean that the Chinese might as well pay their workers a decent rate by Western standards or be taxed, and that they might as well have environmental and labor provisions that are the equivalent of ours, as they'd be paying for them anyhow.

That's the solution as I see it. Of course, the problem with this solution is that it would take an enormous bureaucracy to puzzle the tax rates out. I suppose that could be funded by the tariff itself, but that wouldn't be easy. Still, maybe it would be a better solution that claiming that the corporate tax rate or mean businessmen are to blame. It wouldn't be perfect, and it would have the unfortunate result of perhaps punishing poor foreign workers who need their jobs, but might lose them. However, at least discussing it in this context might be productive in and of itself, so that the real cause and effect of things is looked at, rather than simple reductions that don't really reflect the realities of the situation.

Monday, July 2, 2012

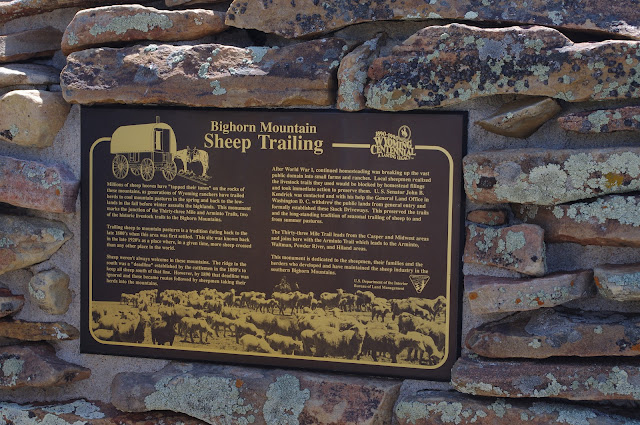

Some Gave All: Bighorn Mountain Sheep Trailing, Wyoming

Some Gave All: Bighorn Mountain Sheep Trailing, Wyoming:

This may seem like an odd one to add here, but it does commemorate, in part, the dead of a war, albeit a private war. This Federal monument commemorates the Wyoming sheep industry, now a mere shadow of its former self. In its early days, the hill behind what is displayed here was the "Deadline", literally the line which sheepmen were not to cross, according to cattlemen, lest they end up dead.

The monument itself recalls a "Sheepherders Monument", a type of rock cairn that sheepherders once used to mark trails, and which are still very common in Wyoming.

This may seem like an odd one to add here, but it does commemorate, in part, the dead of a war, albeit a private war. This Federal monument commemorates the Wyoming sheep industry, now a mere shadow of its former self. In its early days, the hill behind what is displayed here was the "Deadline", literally the line which sheepmen were not to cross, according to cattlemen, lest they end up dead.

The monument itself recalls a "Sheepherders Monument", a type of rock cairn that sheepherders once used to mark trails, and which are still very common in Wyoming.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)