Me, third from right, when I thought I had a career in geology, and probably in coal.

Me, third from right, when I thought I had a career in geology, and probably in coal.

There is a lot of speculation about a revival in the future of coal around here. I'm skeptical. This doesn't mean that I come from the outside where coal is simply a freakish oddity. No, I'm pretty familiar with coal. . . personally. At one time, coal, I thought, would fuel my career. When other students in the UW geology department of the early 1980s were planning on becoming petroleum geologist, I focused on coal, which wasn't suffering. . . at first, the way oil then was. Of course, it came to, and I went from the geology department into under employment so my plan failed.

The irony of that is that my choice on coal as a focus was intentional. I could see the handwriting on the wall in regards to employment in the oil industry. Others seemingly couldn't, or having entered onto that set of railroad tracks they just couldn't get off. Coal, on the other hand, was doing fine in the early 1980s. . . at first. There were coal mines operating at that time which aren't now. Indeed, there was an underground coal mine in Hanna, a continuation of a situation that had existed well into the early 20th Century.

Well, that didn't work out the way I'd panned and by 1985, when I approached graduation from the University of Wyoming, after five years of effort (five was typical for geologist, that was five full semesters) I graduated into being an . . . .artilleryman.

Yup. Artillery. The rescuer of my economic fortunes.

I'd joined the National Guard right out of high school and was still in it in 1985 when I graduated. The Guard basically employed me on a semi full time basis for a year while I tired to find a job. I couldn't, of course, so I ended up going back to school to obtain a JD. Indeed, relating back to the Guard, I've felt guilty ever since as I let my enlistment expire in 1986 just before I went back to law school as I believed all the propaganda I'd heard about how hard law school is. Hah! It's nothing compared to obtaining a bachelors in geology.

My main employer, right after receiving my bachelor's degree.

My main employer, right after receiving my bachelor's degree.

Anyhow, in that period of time between my general geology studies at Casper College (during which I really picked up a love of geomorphogy) and my graduation, the first time, at the University of Wyoming by which time I'd picked up a focus on coal, I learned a lot about coal. At the same time I nearly obtained enough credits for a BA in history, which perhaps reflects a natural interest that reflects itself back here.

So, perhaps in some ways, I'm uniquely suited to ponder the long decline of coal. Or at least I have.

And indeed the path of coal, and its long slow decline, is highly relevant to where we find ourselves now. Lots of people in the coal states believe that the election of Donald Trump is going to revive the fortunes of coal. Here in Wyoming quite a few people are so acclimated to coal paying the bills that they can't imagine anything else. Indeed, just this past weekend I was at a public event, wearing my shabby (truly) Carhartt coat and my Stormy Kromer cap, probably looking like a guy who had shoveled a lot of coal (and indeed I have shoveled a little) and was accosted by a person sitting under a banner proclaiming something about a "return" to liberty and the Constitution who started off on a speech about would I like to sign a petition in opposition to any kind of new taxes. No, I won't sign that as I just don't see coal being able to pay the Wyoming freight in the future anymore. Maybe some other mineral or minerals can, but coal isn't going to be able to the way it once did (and besides, I'd be unlikely to sign anyway as I tend to find that people are always opposed to new taxes but not bothered by demanding that the things taxes pay for are really good).

I think the path of coal, being familiar with it, might be best illustrated by a few rough dates and illustrations. Its something that should be considered.

So let's start around 1900. That was a world fueled by coal (and by wood). Sure, kerosene was around, and it had replaced whale oil to a large extent. I have around here a draft post, now months and months old, building on a George F. Will column that noted:

As I will note, I don't dispute the details that Will recites here, but I do doubt the "more medieval than modern assertion in a major way. Indeed, some of these things argue, I think, the other way around and I think that misstates the nature of the Medieval world.

But noting what Will states about lights, we note what he said, and further note that it was accurate.

- "No household was wired for electricity"

This is quite true.

- "Flickering light came from candles and whale oil,"

Whale oil chandelier, photo from the Library of Congress. Up until the Will entry, I'd never even considered there being such a thing as a whale oil chandelier.

And so, in many places it did. But coal fueled a lot of other things.

But let's consider coal in 1900.

It fueled the ships.

USS Ohio, approximately 1898, as the USS Maine, which sank in a coal explosion in 1898, is in the background.

It fueled the trains, the only significant interstate transportation that existed.

New Your central yard, about 1907.

It heated the homes, where wood did not.

And it fueled industry, particularly the steel industry.

Blat furnace, about 1905.

And then things began to change.

It really started with navies in some ways, although some might argue that it started with hydroelectric. We'll start with navies.

Navies had been powered by sail up until the mid 19th Century but already by the time of the American Civil War that was changing. The U.S. Navy may have had its grandest ships under sail during that war, but coal fired wheels were being introduced even then. And the scary smoke belching squat "monitors" that signaled the end of the age of sail were coal (and perhaps wood) burning beasts. Slow, hardly seaworthy, but iron clad. It was pretty clear by 1865 that the age of militarized wind was ending.

And indeed the Naval reformation that occurred after the American Civil War is incredibly stunning. Everything about navies soon changed. By the 1890s every major navy in the world was building ships that look odd to our eyes, but which still look familiar . Big guns on big ships powered by coal replaced sailing vessels, and the general purpose yeoman sailor was replaced by the specialist. At about this time, in fact, the U.S. Navy started to switching from a navy drawing its recruits mostly from port towns, and which was in fact an integrated navy, to one which was segregated which drew its recruits from the interior of the country. A wood and sail navy required men who had grown up near, or even on ships, and who knew the ins and outs of sail. That was a multi ethnic, polyglot group of men who in some way resembled the men in every port town around the world more than they did the men in the interior of their own countries. It's no accident that the first Congressional Medal of Honor to go to a foreign born serviceman went to a sailor, in action during the American Civil War fighting a naval battle in. . . . .Japan.

The naval battle in Shimonoseki Straits where an English sailor serving on board the USS Wyoming won a Congressional Medal of Honor. Note that these ships already featured coal fire steam, in addition to sail.

While there was a sail and steam age, i.e., an age that combined both, for navies it wouldn't last long. For commercial shipping it lasted longer, and indeed the age of sail itself lingered on until after World War Two, amazingly enough, in some usages. But for big ships, coal fired boilers were the norm before the turn of the century. Sail lingered, but only lingered.

And so we entered the coal fired world. The degree to which coal fired everything, almost, is stunning. If we take the world of 1900 heavy long distance transportation of all types was coal fired. Trains and ships, that is. Local transportation was seeing the beginnings of the Petroleum Age, but only the beginnings. Locally, it was very much a horse oriented world, and indeed the railroads themselves caused a massive boom in heavy hauler horses around the turn of the prior century which gave us the really big draft horses, rather than farms as we so often imagine. Something had to hault hat weight from the railhead to the warehouse.

And heat was going the way of coal. Coal fired, well fires, heated homes all around the country everywhere. Boilers for apartment buildings, furnaces in homes. Wood remained, but it was coal that was the oncoming fuel.

A World War One vintage poster of the United States Fuel Administration. This period poster nicely illustrates how coal fit in. Homeowners were being urged to buy coal early in the year. That coal wasn't delivered, in this poster, by a truck, but rather by a dump wagon drawn by heavy draft horses. Given the light dress of the laborer and the depiction of foliage the poster must have been released during the summer.

It is, in short, impossible to overestimate the importance of coal around 1900. It was called King Coal for a reason.

But things were beginning to slowly change.

For one thing, petroleum was creeping in. Not in a massive way, but in a way that was clearly predictable. George Will spoke of whale oil lamps, but by the second half of the 20th Century kerosene lanterns were very common and their advantages very obvious. Following in their wake came gas lanterns and by necessity, piping for natural gas. It wasn't long after that in which the first gas stoves were introduced. Already by the early 20th Century, therefore, there was gas lighting and gas stoves.

And gasoline was already making its appearance in the internal combustion engine by 1900.

Very early internal combustion engine.

We've dealt with automobiles elsewhere, but we've become so acclimated to them that we rarely think of their history. Automobiles were a 19th Century invention, albeit a very late 19th Century invention, not a 20th Century one. That doesn't mean that they replaced the horse right away, that would hardly be true, but they do go back aways. And they were not, and we should not pretend, that they were any sort of a threat to coal at first. Not at all. Cars, trucks and motorcycles were competition for the horse, not the train and certainly not the ship or even the barge.

Truck waiting in line with big long line of coal wagons, some time prior to World War One.

Which takes us back to ships.

And, more specifically, the Royal Navy.

For decades, indeed centuries, the world's biggest and best navy was the Royal Navy. This does not mean, however, that there was ever a day in which some other navy wasn't contending with the Royal Navy for that position. And given that, the British basically engaged in a naval arms race that lasted well over a century. And that mean that it needed to always be on the alert for a technological advantage.

And coal had given one. Steam meant that large steel ships were able to be constructed, fired by coal fueled boilers. They had two significant disadvantages however.

Smoke and spontaneous ignition.

Let's talk about smoke first, the disadvantage that was always there.

Their smoke was visible all the way over the edge of the horizon.

This is something that people who are more familiar with ships of the World War Two era don't instantly recall about earlier steel ships, but coal fires smoke and hence coal fired boilers likewise smoke, or rather the coal fires smoke

The Great White Fleet, and great clouds of black smoke, December 16, 1907.

Prior to the advent of air reconnaissance and radar the spotting of enemy fleets, or for that matter friendly forces, was done by the naked eye. And it was a matter of absolutely vital concern. In the vastness of the ocean ships at sea had always scoured the horizon for signs of enemy ships, and even clues that seem slight to landlubbers were picked up by trained sailors. Sailors looked, in prior eras, for sails and masts on the horizon, with the assistance of spyglasses. By the time of dreadnoughts, however, they were looking for the faintest hints of smoke, and coal fired boilers provided plenty of it. Teams of sailors searched the horizon with massive binoculars looking for that wisp of smoke, which was often more than a wisp.

The next danger was rarer, but not so rare as to not be a serious problem. Spontaneous combustion.

Coal has a well known propensity to self heat and to make it worse, the better the coal grade the bigger the problem. Exposed to air and moisture coal begins to engage in an exothermic reaction and can relatively easily self heat to the point where it ignites. Moreover, as it self heats and heads towards ignition it drives off highly flammable hydrocarbon gases. Indeed, heating coal intentionally in a controlled environment is a means of producing those gases and has sometimes been thought of as a method of producing them, although its never proven to be an efficient means of doing so.

Coal is so prone to spontaneous combustion that coal self ignition is a natural phenomenon. It simply happens where coal gets exposed to sufficient oxygen and moisture. Anyone who has ever spent any time in an open pit coal mine has seen coal simply burning on its own, as I have.

There are ways to combat this, of course, but the problem is uniquely acute for ships. Ships must store coal in large bunkers and must taken on a lot of coal at certain points. Ships are wet by their very nature. So any coal burning ship has, at some point, a lot of coal with just enough oxygen and moisture to create a problem.

This proved to be a real problem for ships and of course there were extreme catastrophic occurrences, the most famous of which is the explosion of the USS Maine. The Maine is an extreme example of what could occur, but any coal burning ship could experience what the Maine did. Basically, in the case of the USS Maine, the coal self ignited and the coal bunkers had sufficient liberated gas to create a massive explosion. Not quite as dangerous, but still a huge problem, a simple self ignition of the coal without an explosion was a disaster, quite obviously, of the first rate requiring sailors to put the coal fire out under extreme danger.

Coal's detriments on ships would have had to be accepted, and indeed they were, but for the existence of alternatives. Indeed, coal survived as a naval fuel for an appreciably longer time than a person might actually suppose, so impressive were its advantages in general. Measures were taken in ship design to try to combat the dangers, such as having the coal bunkers placed near outside ship's hulls such that the coolness of the water would translate to them, and placing sailors bunks along the bunker's walls so that the sailors could tell if heat was building, but the dangers were real and known. Also known was that there was an alternative, oil.

By the turn of the century naval designers were aware that oil could be used to heat boilers just as coal could, and they began to study it in earnest. Indeed, not only could it be used, but it had numerous advantages.

Unlike coal, petroleum oil for ships fuel did not result in much smoke. It resulted in some, but not anything like that which coal put out. The smoke from a single ship was much less visible and suffice it to say the smoke from a fleet of ships was greatly reduced. Again, there was smoke, but not smoke like that put out by coal fired boilers. Indeed, it was so much reduced that to a large degree detection of ships over the horizon by the naked eye was approaching becoming a think of the past.

And petroleum does not spontaneously self ignite. A big vat of petroleum can sit around forever and never touch itself off. This does not mean, of course, that its free from danger. It isn't. But some of the dangers it poses were already posed by coal, but in lesser degrees. Petroleum burns more freely than coal by quite some measure and once it ignites putting it out is extremely difficult. Sparks, other fires, etc., all pose increased dangers for petroleum over bunkered coal, but they existed to some degree for bunkered coal already.

And petroleum is more efficient and easier to use for ships. Coal was basically stoked by hand, a dirty laborious job. But petroleum wasn't. Petroleum burning boilers were fueled by what amounts to a plumbing system involving a greater level of technical know how but less physical labor. And oil had double the thermal content of coal making it a far more efficient fuel which required less refueling. And on refueling, ships fueled with oil can be refueled at sea. Ships fueled with coal cannot be. Indeed, the maintenance of coaling stations in the remote parts of the globe was a critical factor in naval planning prior to the introduction of oil.

Which isn't to say that there weren't some unique problems associated with petroleum for ship.

For one thing, the fact that it spreads out when leaked and can more easily ignite meant that petroleum added a unique and added horror for a stricken ship. Coal fired ships that were simply damaged and sinking were unlikely to cause a horrific sea top fire. Petroleum ships are very likely to do that. And the risk of a munitions caused explosion is increased with petroleum fueled ships. A torpedo into a coal bunker might blow a coal fired ship to bits with an explosion or might just sink it. With a petroleum fueled ship the risk of an explosion in such a situation is increased as is the risk that oil on the water will catch on fire or otherwise kill survivors.

A huge factor, however, was supply.

By odd coincidence all of the major naval powers, save for Japan, had more than adequate domestic supplies of coal. Some had very good supplies of coal, such as the United States, United Kingdom and Imperial Germany, within their own borders. Japan nearly did in that it obtained it from territories it controlled on the Asian mainland, although that did make its supply more tenuous. At any rate all of the big naval powers of the pre World War One world had coal supplies that htey controlled. That's a big war fighting consideration. Of the naval powers of that era, in contrast, only the United States and Imperial Russia had proven petroleum sources they controlled, and Imperial Russia had proven it self to be a second rate naval power during the Russo Japanese War.

Switching from coal to oil did not occur in the Royal Navy, or any navy, all at once. The decision was made somewhat haltingly and it was an expensive proposition to convert an entire navy to oil. Britain started to convert prior to World War One but it didn't complete the process until after the war. Still, its decision to start constructing capitol ships as oil burners in 1912 was a huge step for a nation that had the world's largest navy but which had no domestic oil production at all. The United States followed suit almost immediately, with its first large ship to be converted to oil, the USS Cheyenne, undergoing that process in 1913.

The USS Cheyenne in 1916 while it was a submarine tender. The Cheyenne was the first oil burning ship in the U.S. Navy, following the lead that the British had started.

The USS Cheyenne was illustrative of something else that was going on, however, that being the increased presence of heavy internal combustion engines for various uses. The USS Cheyenne had been built as a monitor, a type of proto battleship (and had been named the USS Wyoming originally) but after its conversion to oil it would become a submarine tender in a few short years. Submarines of the era were light vessels and, like a lot of light naval fighting ships ,they were diesels. Marine diesel engines were replacing boilers completely in lighter vessels and of course diesel fuel is a type of oil.

Diesels in that application show that industrial diesel engines had arrived.

By World War Two every navy in the world was an oil burning, not a coal burning, navy. And it wasn't just navies. Merchant ships had followed in the navies' wakes. They were now oil burning too for the most part. Coal at sea had died.

Giant marine diesel engine circa 1920.

The demise of coal at sea did not equate, of course, with the universal demise of coal, and this is very important to keep in mind. Entering into the period of history we've been discussing, roughly 1900 to 1920, coal may have lost its crown at sea, but it remained hugely important, arguably increasingly important, elsewhere. It continued to be the fuel of heavy transportation, IE., for trains, it continued to heat homes and it fired an ever growing number of power plants. Indeed that last application can't be overstated as in this same period the Western world was electrifying. So whatever position it may have lost on the waves it was likely more than making it up on land.

Still, the trend line had been set.

And it would next show itself with transportation.

At least according to one source written in 1912 coal fueled 9/10s of all locomotive engines at that time. The other 1/10th would have been fired by wood or, yes, oil.

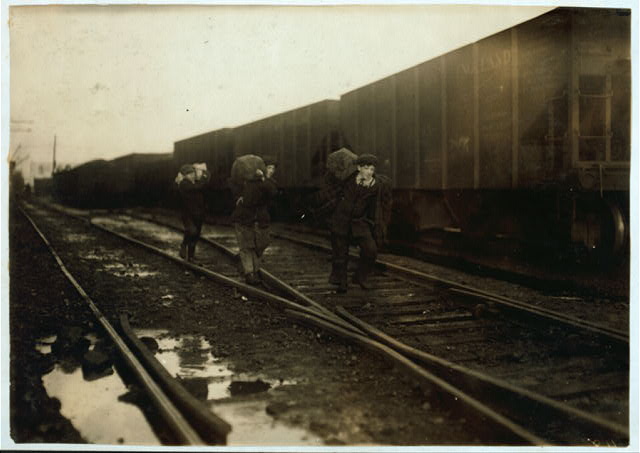

This photograph will appear again in a series of photographs on the centennial of their having been first taken, in January 1917, but these teenagers are stealing coal from a rail yard. They are probably taking it home for heating fuel or are selling it to Bostonian's who probably knew darned well these kids had taken it illegally from the yards. For that matter, the railroad likely knew they were taking it too. Even today, decades after the end of the use of coal for locomotives the paths of old railways can be found by the coal ash and coal that the trains dropped as they passed by. I've walked the path of the old UP here and there down by Laramie doing that.

Wood, I should note, may seem strange for a locomotive engine of that era, but it really shouldn't. The goal of any fuel used in a locomotive engine is to produce steam and burning wood will produce steam. Wood isn't an efficient fuel for that but it was a common one very early on. Most locomotives were switched to coal after the Civil War, assuming that they were not burning it already, but where wood was locally plentiful and the engine had a local use, as for a small engine associated with a timbering operation, wood was kept in use.

Indeed, as a total aside, during World War One some small German engines were made that burned trash. Coal is a military fuel, Germany's (and Poland's) coal is very good, but as a military fuel conservation was the rule of the day.

At any rate, in 1912 less than 1/10th of all steam engines were burning oil, but what is telling there is that some were. So here too a trend line had started.

In following years more and more steam engines became oil burning engines. The reasons may not be entirely clear and are somewhat subtle, but some of them have been touched upon already above. Oil is a more efficient fuel. Not so much so, however, that all locomotives were switched to it. The famous Union Pacific Big Boys, for example, were coal burning to the end.

Union Pacific Big Boy. These were coal burning their entire career.

What did the coal burning locomotive in, in the end, or more properly the steam engine in, was the diesel.

Diesels Electric trains proved to be a better and more efficient option for train engines in the end. Contrary to what some may think these locomotives do not work like a diesel truck in that the engine does not power the drive wheels. Rather the diesels are big generators and the trains are essentially electric. By the same token, in the proper settings, trains run from overhead electric lines. Either way, this type of engine did in the steam engine.

Now then, looking at it, we see that coal went from the main fuel for ships and trains to a remnant fuel for both in a fifty year period. Hardly overnight, but clearly observable. A person living in the era, if they cared to notice the trend, would have noticed. Certainly, for example, if you lived in Rawlins Wyoming and looked out towards the Union Pacific Railroad yard over the course of an average life, if you'd lived in this period, you would have seen it gone from a busy smoky and sooty yard to one which had only the blue haze of diesel fuel above it. And given that Rawlins is just seven miles from Sinclair, where a refinery is located, but also is surrounded by coal deposits and actually had its origin as a coaling location for the Union Pacific, the change would have been pretty obvious. If you worked in the big underground mines in Hanna you might actually be slightly worried.

Which isn't to say that coal stopped being used. Not hardly. It was still heating homes all over, including in Wyoming, and it still was the fuel for power plants.

Let's turn to domestic coal use, as we haven't really touched on that much.

Lennox "Torrid Zone" coal furnace

Now, as we've seen above, coal was a basic heating fuel early in the 20th Century, having replaced wood in that role to a large extent. During World War One Americans were urged to stock up on heating coal early, which meant filling their coal rooms full during the summer rather than waiting until winter. Coal soot was such a prominent part of big city life that it came to be an accepted part, even contributing to the legendary concept that London was foggy. It wasn't so much foggy as it was sooty. This use of coal continued on for a very long time, and indeed here in Wyoming, which switched to gas early, people still ordered coal for heating fuel at least as late as the 1940s.

Coal furnaces in the Library of Congress, 1900. Shoot, and Washington D. C. isn't even all that cold.

But over time this changed to where heating oil, yes another use of petroleum oil and natural gas began to replace coal. By the 1970s at least the price of heating oil became a major factor in annual fuel price concerns, but nobody really thought much of coal for the same purpose. You can still buy a coal furnace today, if you are so inclined, but very few people do. So yet another use of coal yielded to petroleum. And here, over time, petroleum has yielded to natural gas and electrical generation.

Workman converting coal furnace to oil during World War Two. Oil was more plentiful and efficient which sparked a government move to convert home heating to oil

Of course electrical generation also became a major use of coal in the early 20th Century, and it remains one today. But, as has been seen from the trend line above, coal isn't the only option, and here too its a declining one. While oil did make an appearance in the electrical generation field oil powered power plants are more or less a thing of the past and coal has outlasted them. There are no oil fired power plants left in the United States and less than a dozen major ones left on Earth. They're yielding, however, to natural gas, which powers quite a few power plants and which as been replacing coal. And there are other means of generations electrical power, including wind power which now is cheaper than other forms of electrical generations in some regions of the United States.

Dave Johnston Power Plant, 2015. U.S. Government photograph.

Okay, so what's the point of this? Well, just this. Coal has been on a long, slow, decline for over a century. It isn't that it doesn't work, it's that it can't compete economically with other fuels that do the same thing in an increasing range of uses. Only in terms of coking for steel production is it indispensable. Indeed, perhaps signalling an international increase in manufacturing, high grade coal for coking has experienced a sharp recovery in recent months. That doesn't do anything locally, however, as our coal is Bituminous Coal, not Anthracite, and therefore can't be used for coking.

This isn't the view of some green fanatic world view. It's dollars and cents, and coal producing regions, such as Wyoming, have to consider this. Without a way to address coal's defects, and soon, its diminished share of the fuel market will be considerably smaller irrespective of any environmental or regulatory concerns. It's been a long trend running back over a century.

_-_6.jpg)