It can no longer be ignored.

Wyoming Territorial Governor John A. Campbell.

Something was going on with facial hair in the late 19th and early 20th Century. And on a massive scale.

In addition to this blog, and my others, I try to catalog Wyoming's history on a daily basis with my

Today In Wyoming's History blog. This being November, I've been running a lot of items on various politicians being elected or appointed, including a lot of them in the 1865 to 1920 time frame. And the evidence is overwhelming. In order to be anything in that time frame, business wise or politically, you had to have some serious mustache action going on.

George A. Baxter. It probably took him longer to grow that mustache and cookie duster than he served as Territorial Governor. Note also the starched upright collar, a type of dress style thankfully now more or less gone.

Francis E. Warren, Congressional Medal of Honor recipient from the Civil War and and one of the longest serving Senators in Senate history. And also father in law to General John J. Pershing. The Wyoming politician had this serious mustache his entire political career, including the point in time when this photo was taken, after the passing of the Great Mustache Era.

Clarence Clark, long serving but forgotten mustachioed Wyoming Congressman.

James Weaver, a surprisingly successful candidate for President on the Populist ticket, who went right from the Huge Beard Era to the Giant Mustache Era.

Now, it so happens that I happen to have a mustache myself, but nothing like the gigantic mustaches so popular in the this era. These mustaches are practically their own species of mustache, bearing a faint resemblance to current mustaches the way that giant animals of the Pleistocene bear a relationship to their smaller cousins today.

How did this occur? It's hard to say. We can tell, of course, that just prior to the Giant Mustache Era there was a Giant Beard Era.

Territorial Governor Moonlight, who'd been a Civil War era general before being appointed Territorial Governor of Wyoming.

Enormous beards seem to have come in during the Civil War. Perhaps everyone was too busy fighting to shave.

Rutherford B. Hayes, whose mouth has completely disappeared from view due to his beard.

Mustaches, however, started to dominate in the late 19th Century. No idea why. And not only mustaches, but the super sized mustache, such as that sported by Theodore Roosevelt.

Zachery Taylor. Apparently razors were in use when he was President, but combs clear were not.

Theodore Roosevelt, who went to the big mustache when was a rancher.

Roosevelt cultivated a thin, very well groomed mustache, until he went to the Dakotas to ranch. At that time, the busy stache was already in vogue in the West. I've heard it claimed that the reason for this is that it keeps the lip from sunburning. Perhaps. At any rate, bug mustaches remain pretty common amongst ranchers and cowboys today, so perhaps there's something to it. And perhaps Roosevelt's adoption of the style helped popularize what was already a growing trend at the time.

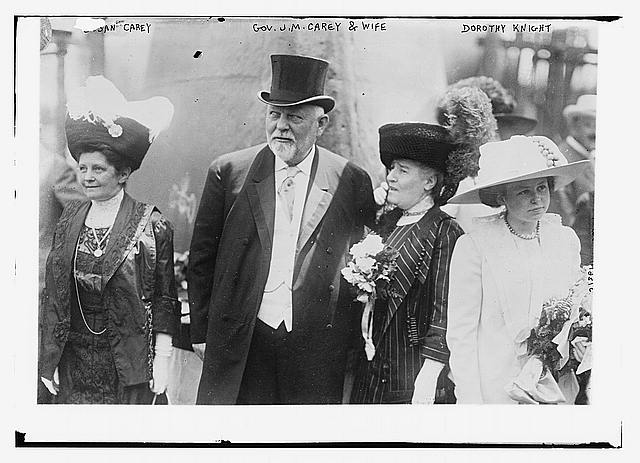

Goatee pioneer Governor Carey. Was Carey a proto-hipster?

And it wasn't just in the United States. It was a global trend. South of the border, Mexican revolutionaries Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa both sported some serious mustaches. Lord Kitchener, the legendary British Field Marshall did as well.

Even now, Lord Kitchener's command is compelling. The mustache the reason?

Frankly, based upon the photographic evidence, I doubt a man prior to 1914 or so could expect to be a success without a serious mustache. Just look at William Jennings Bryan, for example. Universally regarded as brilliant, he just couldn't get himself elected President. And he didn't amount to a great Secretary of State when appointed by the equally clean shaven Woodrow Wilson, a President who couldn't persuade Congress to approve the Versailles Treaty. Perhaps it was the lack of a mustache that left the Senate lukewarm about the entire deal.

Writer Owen Wister. He didn't go into law like his father had hoped, but the sensitive writer had to be taken seriously in print, with a mustache like that.

Well, this leads us to an obvious conclusion. In this season of seemingly ongoing political confusion and strife we're left wanting for character in our leaders. Gen. Petraeaus engages in activity that brings him down. Even many Republicans and Democrats are less than enthusiastic about their recent candidates, Mitt Romney and Barrack Obama. Clearly something is missing. And that something must be the serious mustache that obviously instilled moral fiber and character in an earlier stalwart generation.

All photographs from our

Flickr site.