Ostensibly exploring the practice of law before the internet. Heck, before good highways for that matter.

Showing posts with label Spanish American War. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Spanish American War. Show all posts

Sunday, February 23, 2020

February 23, 1920. The death of Maj. Gen. LeRoy Springs Lyon.

You've likely never heard of him, and for that matter, I hadn't either.

Rather, I'm posting this item on Gen. Springs as he's interesting example of a World War One vintage U.S. senior officer whose military career was cut short by his premature death at age 53.

He entered the Army upon his graduation from West Point in 1891 and was commissioned as a 2nd Lt. in the cavalry, and assiged to the 7th Cavalry. He was a scout, early on.

In 1898 he made the unusual choice to switch branches, something rarely done in the U.S. Army at the time, and went to Coastal Artillery School. After graduating from the school, he was assigned as an aid to Gen. Royal T. Frank, and continued on in that role during the Spanish American War. Following the war, he was transferred to the 2nd Artillery Regiment, in effect yet another branch switch from Coastal Artillery to Field Artillery, and commanded it in the field in Cuba from 1899 to 1900. He later served in the Philippine Insurrection and in the Canal Zone before retunring ot the U.S in 1915, where he commanded Camp Bowie. During the Great War he was in command of the 31st Division at first and then the 90th Division.

Like most brevetted generals, following the war the Major General returned to his permanent rank of Colonel and was assigned to command the Field Artillery Basic School which was located, at that time, in Camp Taylor, Kentucky.

His wife Harriet, whom he married in 1903, was ten years his junior and outlived him by forty-one years.

Saturday, August 10, 2019

August 10, 1919. The Motor Transport Convoy rests in Laramie. Troop A, New Jersey State Militia Reserve trains at Denville.

The Motor Transport Convoy spent their Sunday in Laramie on this day in 1919.

The weather was "fair and cool", which would be a good description of most summer days in high altitude Laramie, which has some of the nicest summer weather in Wyoming. Wind and rain in the late afternoon is a typical feature of the summer weather there.

In New Jersey, where the weather probably wasn't fair and cool, Troop A of the New Jersey State Militia Reserve was training.

The weather was "fair and cool", which would be a good description of most summer days in high altitude Laramie, which has some of the nicest summer weather in Wyoming. Wind and rain in the late afternoon is a typical feature of the summer weather there.

In New Jersey, where the weather probably wasn't fair and cool, Troop A of the New Jersey State Militia Reserve was training.

Troop A, New Jersey State Militia Reserve, at Denville, New Jersey.

State units during World War One and World War Two are a really confusing topic. All states have the ability to raise state militia units that are separate and part from the National Guard, but not all do. Generally, however, during the Great War and even more during the Second World War, they did.

State units of this type are purely state units, not subject to Federal induction, en masse. Their history is as old as the nation, but they really took a different direction starting in the Spanish American War.

Early on, all of the proto United State's native military power was in militia units. There was no national army, so to speak, in Colonial America. The national army was the English Army, which is to say that at first, prior to the English Civil War, it was the Crown's army. That army was withdrawn from North American during the English Civil War of the 1640s and 1650s, in which it was defeated. During that decade long struggle British North America was defended by local militias. When British forces returned, which they did not in any numbers until the French and Indian War, it was the victorious parliamentary army, famously clad in red coats, which came back.

Not that this was novel. Early on all early British colonies were also defended only by militias. The Crown didn't bother to send over troops to defend colonies, which were by and large private affairs rather than public ones anyhow. At first, individual colonies were actually town sized settlements, with associated farmland, and they had their own militias. Indeed, as late as King Philip's War this was still the case and various towns could and did refuse to help other ones and they had no obligation to do so.

Later, when colonies were organized on a larger basis, the proto states if you will, militia units were organized on that basis, although they were still local units. I.e., towns and regions had militias, but the Governor of the Colony could call any of them out. That gave us the basic structure of today's National Guard, in a very early fashion, and in fact that's why the National Guard claims to be the nation's oldest military body with a founding date of December 13, 1636.

Colonial militia's fought on both sides of the American Revolution, depending in part upon the loyalty of the Colonial governor at the time they were mustered as well as the views of the independent militiamen. They formed, however, the early backbone of the Rebel effort and indeed the war commenced when British troops and militiamen engaged in combat at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775.

The Revolution proved the need for a national army to contest the British Army and hence the Continental Army was formed during the war and did the heavy lifting thereafter. Militia, however, remained vital throughout the war. Following the British surrender, there was no thought at all given to keeping a standing national army and it was demobilized and, for a time, the nation's defenses were entirely dependent upon militias, with any national crisis simply relying upon the unquestioned, at that time, ability of the President to call them into national service if needed.

The lack of a national army soon proved to be a major problem and a small one was formed, but all throughout the 18th and the first half of the 19th Centuries the nation's primary defense was really based on militias, with all males having a militia obligation. The quality of militia units varied very widely, but by and large they rose to the occasion and did well. Interestingly enough, immediately to our north, Canada, a British Colony, also relied principally on militias for defense and its militias notably bested ours during the War of 1812.

The system began to demonstrate some stresses during the Mexican War during which New England's states refused, in varying degrees, to contribute to the nation's war effort against Mexico. A person can look at this in varying ways, of course. While we've taken the position here that the Mexican War was inevitable and inaccurately remembered, the fact that the Federal government had to rely upon state troops did give states an added voice on their whether or not they approved of a war. The New England states did not. The Southern states very much did, which gave the Mexican War in its later stages an oddly southern character.

The swan song of the militia system in its original form came with the Civil War. Huge numbers of state troops were used on both sides, varying from mustered militia units that served for terms, to local units mustered only in time of a local crisis, to state units raised just for the war. But the war was so big that the Federal Army took on a new larger role it had not had before, and with the increase in Western expansion after the war, it was reluctant to give it up. Militia's never again became the predominate combat force of the United States. Indeed, there was long period thereafter where the militia struggled with the Army for its existence, with career Army officers being hugely crabby about it.

That saw state militias become increasingly organized as they fought to retain a military role, and by the Spanish American War they were well on their way to being the modern National Guard. The Dick Act thereafter formalized that. But the Spanish American War, which was also very unpopular in New England, saw some states separate their militias into National Guard and State Guard units, with State Guard units being specifically formed only to be liable for state service. Ironically, some of the State Guard units that were formed in that period had long histories including proud service in the nation's prior wars. This split continued on into World War One which saw some states, such as New Jersey, muster its National Guard for Federal induction but its State Guard just for wartime state service.

That pattern became very common during the Great War during which various states formed State Guard units that were only to serve during the war for state purposes. Naturally, the men who served in them were men who were otherwise ineligible for Federal service for one reason or another, something that has crated a sort of lingering atmosphere over those units. When the war ended a lot of states that had formed them, dropped them, after the National Guard had been reconstituted.

This patter repeated itself in World War Two during which, I believe, every state had a State Guard. After the Second World War very few have retained them, and most of the states that have, have a long history of separated militia units. Today those units tend to provide service for state emergencies, but they also often serve ceremonial functions. An exception exists in the form of the Texas State Guard, which was highly active on the border during the Border War period, and which was retained after World War Two even after the Federal Government terminated funding for State Guard units in 1947. They've continued to be occasionally used in Texas for security roles.

In New Jersey, we'd note, the situation during the Great War was really confusing, as there were militia units organized for the war, as well as separate ones that preexisted it. A lot of those units would soon disappear as the National Guard came back into being, although New Jersey is one of the few states that has always had a State Guard since first forming one.

Monday, February 4, 2019

Pinks and Greens

Having a taste for history, and a dislike the of the last two Army dress uniforms, you'd think that I'd like the Army having gone to the new "pink & green" uniform. Indeed, I thought I'd feel that way as well.

The new Army Green Uniform based on the old officer's Army Service Uniform that came in, in stages, during the 1920s and 1930s and lasted until the mid 1950s, and the current Army Class A blue uniform in the center.

But I don't.

Maybe I'll change my mind, but to my own surprise, I don't like it. It strikes me as sort of staged and made up, or maybe even a little pathetic to some degree.

Okay, what am I even talking about? That requires some background explanation, and for that I have to go about it in sort of a round about way or a direct line in a historical way. I'll do the latter.

I don't intend to do a "history of Army dress uniforms" here (really, I don't, even if I end up doing just that), so I'm just going to leap in just prior to World War One and go from there, more or less. We've been looking at a lot of photographs of the Great War and therefore, for anyone following this blog, there's a ready frame of reference.

U.S. Army officers on their way home from France after the war. Note the stitching on their great coats. All wear the then new overseas cap.

Up until after World War Two the Army had a "service uniform" and a series of dress uniforms. The two were not the same. Dating back to the Revolution, the Army's more or less official color was blue, which impacted both types of uniforms early on and dress uniforms to this day. I'm not exactly certain why blue came to be the American Army's color, and I'll have to look it up, but I think it may have actually gone as far back as the French and Indian Wars for colonial militia. It became the official color for the Continental Army in 1779. That distinguished Americans from the British who wore red, and I do know how that came about but it was no doubt a very useful fact for both armies during the Revolution, as identification of troops by color of uniform was an absolute necessity in the dense gun powder smoke of the day. Red was the color of Cromwell's New Model Army that prevailed in the English Civil War and replaced the army of the crown.

Wounded Army offices, 1918. A couple of these men are blind.

Blue, indeed a very dark blue, was used for all uniforms pretty much (there are exception) in the U.S. Army up until the 1890s when smokeless powder made it clear (Plains warfare was already actually making it clear) that the era had come when uniforms should help hide a soldier rather than make him more visible, so the Army went to natural colors for field uniforms. I've dealt with that earlier in the blog, and I'm not going to go into it in depth here, but going into World War One that meant that the Service Uniform was a earthy green color during the cooler months that's generally referred to currently as "Olive Drab" and a tan that Americans call khaki in the hot months.* Olive drab, abbreviated to "OD", is confusing, as there's a zillion different shades of it and some are much different from others. But for convenience sake, we'll refer to it as OD here. For solders serving in a very, very hot tropical environment there was a white uniform of cotton with white coat and white breeches.**

74th Infantry, 1918.

Going into the Great War, the Army Service Uniform, i.e., the field uniform, consisted of OD breeches, an OD wool shirt, OD wool breeches, an OD wool service coat, an OD campaign hat, OD leggings and russet service shoes (boots) for enlisted men in most regions. For those serving in hot locations during the summer all the same would be true except the color was now an odd OD and the fabric cotton.*** Most soldiers serving in the U.S. Army during World War One only received the wool uniform, and indeed even during the Punitive Expedition soldiers wore the wool uniform into Mexico. This change in patterns had come about in 1912, and it reflected the rapid evolution of uniforms at the time. The pattern changed again in 1917, although it really takes an experts eye to be able to tell one pattern in this era from the next. Indeed, the overall patterns were so close to the British ones that British uniforms were in fact issued to American soldiers on some occasions.

For officers the uniform was very similar except that officers did not normally (hardly ever) wear leggings and instead wore riding boots and spurs. Both enlisted men and officers were issued OD ties, although you usually only see them if the men are not wearing their Service Coast as the weather was warm.

Wyoming National Guardsmen mustered in 1916 wearing the uniform that, for the most part, would serve all the way into the 1920s. While it can be somewhat difficult to tell due to the size of the photo, this photograph does a good job of illustrating that the enlisted men's uniform and the officers were essentially the same. Two officers can be seen on the left margin of the photo as viewed, one of whom has omitted his service coat. Both are wearing riding boots rather than leggings, which is the only easy way to distinguish between them.

This is one of many photos of American servicemen I've run in recent months wit this one giving a good example of the variety in uniforms. The officer on the left, as viewed, is not wearing an official pattern uniform at all, but the other two officers are. The cut of the pockets is notably different from that of the enlisted men's uniform. All wear the wartime Same Browne belt that came in during the Great War from the British. The officer on the left is wearing non pattern boots, which was highly common. The other two officers are wearing "field boots", a type or riding boot that is still worn by equestrians today.

A very dark blue Dress Uniform also existed for enlisted men and officers, but during World War One it wasn't issued to most troops. It was actually somewhat similar to the service uniform, actually in cut and appearance except that it was very dark blue and featured larger and more elaborate rank insignia and flourishes, recalling the 19th Century blue uniform fairly strongly. Indeed, the prior dress uniform of that type, which was very close in pattern, had actually been issued to some mustering state units in the Spanish American War who, at least at first, were apparently not aware that it was as dress, not a service, uniform.****

World War One recruiting poster showing a cavalryman, mounted, and an infantryman, dismounted. Both men are shown in their Dress Blue uniform, which would not have been worn in the field, and the scene oddly depicts frontier service more than it does contemporary World War One service. This does provide, however, good examples of dress uniforms of the period.

For the most part, the service uniform was worn for everything, and indeed, it was well suited for that.

There was some variety in this uniform. For one thing there was as Service Cap which was a wheelhouse cap. That wasn't really for field use but for garrison use and similar duty. Mounted men's breeches were foxed and differed from dismounted service men. The cut of the officer's service coat was different the enlisted men's and of much finer material. There was as summer or hot weather version of this uniform, although you don't tend to see it in use much even in the summer, which was made of cotton rather than wool, although the headgear was the same. There was a tremendous amount of leeway in footgear for officers who frequently didn't wear the standard field boot but some other variety of riding boot, and the leggings for mounted enlisted men were faced on the inside unlike those for dismounted men.

Okay, that's likely confusing but its' only background and will have to do.

At the same time that this was the Service Uniform, the Army had a Dress Blue uniform, as noted. For some reason this seems to be poorly understood but its' well established. That uniform retained the traditional blue color of the United States Army in the coat, which was a very dark blue. Trousers were light blue and for NCO's featured a stripe that indicated the soldiers branch (i.e., cavalry, infantry, artillery, etc.). Some coloration of insignia likewise indicated branch, while other coloration did not. The hat was the wheelhouse cap.

U.S. Army uniforms changed very little during the Great War but they did change a little. Sam Browne Belts were introduced for officers, taken from the example of European armies. The Overseas (flat) cap was introduced to replace the campaign hat in Europe due to the introduction of the M1917 helmet to combat use. The flat French pattern had was in fact the French pattern at first, but by the end of the war a more stylized, better looking, and less functional version had been introduced.

Two officers of the "Lost Battalion" wearing late war U.S. Army service uniforms featuring the second patter of Overseas cap. The officer on the left wears a Same Browne Belt. Maj. Whittlesey, on the right, should be wearing one but isn't. His service coat is an overseas contract version manufactured by the British, which is evident as the collar folds down rather than stands up.

We've run this photograph before, as frequent viewers will recognize, but it contains a wealth of information on late war U.S. Army uniforms. The General officer on the left wears the Service uniform for an officer of the U.S. Army, but with private purchase riding breaches and private purchase field boots. His spurs straps also depart from the issue pattern. The Overseas cap is an early pattern. The Marine Corps officer on the right wears the Marine pattern of Service uniform which was a much darker olive shade and which featured, by this point, the new pattern Overseas cap. His boots are actually Service Shoes with leather leggings, which would also have departed from issue.

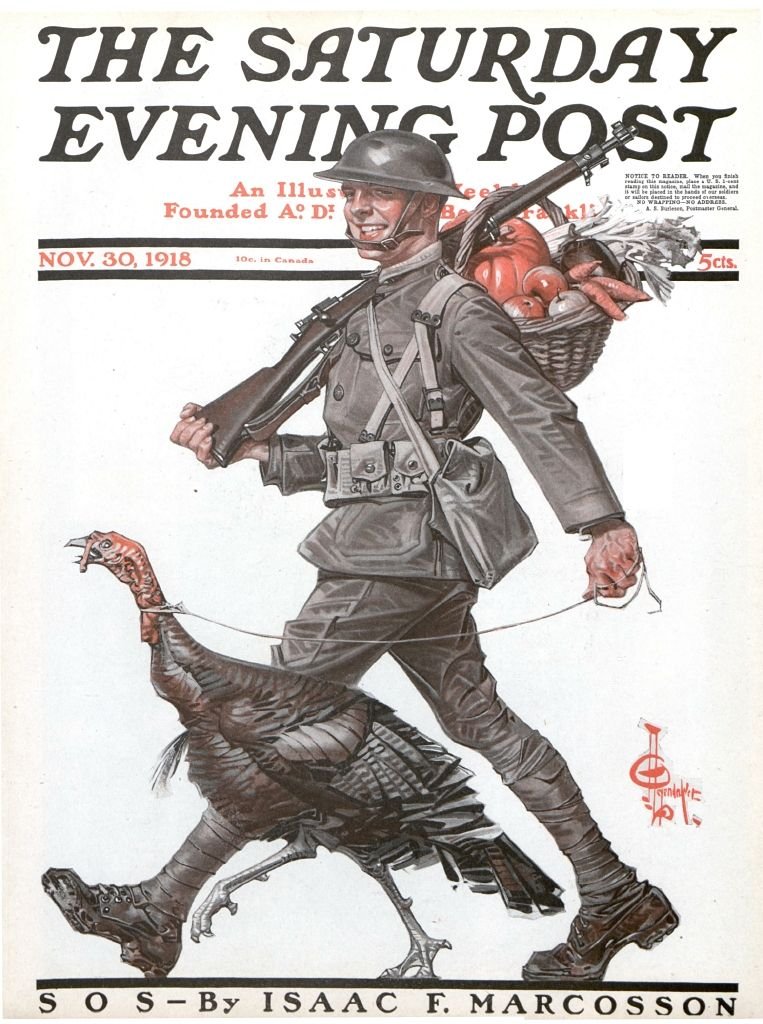

Leydecker illustration of the late war enlisted uniform which is, as always, technically correct for this period. By late war the Army had gone to the British pattern puttees rather than leggings for European use and this soldier is wearing the war time "Pershing boots" which were roughout and hobnailed. The color is incorrect, which I've been blaming on Leyendecker, but it turns out that had something to do with the dies being used by the Saturday Evening Post.

After the Great War the Army retained some of the wartime innovations in the uniform and dropped others, with the elimination of puttees being particularly notable. But by the early 1920s the Army was discontent with the world War One uniform and began to change them.

And that's where this story gets really complicated.

One of the things that happened after World War One is that the uniform entered an oddly impractical stage. It's almost like the Army didn't expect to fight any more wars after the Great War.

Hmm. . . .

The first change, and it was a sign of things to come, came in 1921 when the Army, which had issued "subdued" rank insignia went to full color insignia. This was an odd development as it was contrary to the trend of camouflage in the service uniform. Then, in 1924 the Army introduced full color brass buttons to the uniform, which was very much counter to this trend.

One of the things that happened after World War One is that the uniform entered an oddly impractical stage. It's almost like the Army didn't expect to fight any more wars after the Great War.

Hmm. . . .

Enlisted men jumping a horse in 1920. The Chevrons of the riding sergeant are visible in the photograph.

Then, in 1926, the Army introduced a completely different service uniform featuring a more "modern" open collared coat, like that worn with sports coats or Edwardian suits appeared in the service coat, even thought that was supposed to be a combat uniform Officers and enlisted uniforms were made highly distinct from each other for the first time since the Civil War. Enlisted soldiers were now issued an OD service uniform with an open collar and, if it was winter, they wore a wool shirt with a black tie. If it was summer, they wore a khaki shirt with a black tie. If they were operating without the service coat, and it was winter, they wore OD wool pants (after 1938, when breeches were phased out) and OD wool shirt with black tie. If it was summer or they were serving in the warm regions, they wore khaki "chinos" (that's where they come from), a khaki shirt and a black tie.

The Army Service Uniform in 1939, for enlisted men. Olive Service Coat, Olive shirt, Olive wool trousers, black tie, leggings, Service Shoes, and field gear. Note the brass buttons. Highly impractical, quite frankly.

Note the tie was always supposed to be black. Soldiers who bought their own often didn't buy black, but OD or khaki, which look better.

Corporal serving in a tropical area prior to World War Two. He's wearing the cotton khaki shirt with black tie, the khaki wool Service coat with chevrons that would be OD and black (khaki private purchase ones were common), and the Service Cap of the wheelhouse type. He's also wearing the heavy leather garrison belt. This was as type of semi dress uniform that was actually fairly rare after the start of World War Two..

Officers, on the other hand, were issued a blizzard of uniforms.

Or, rather more correctly, they had to buy a blizzard of uniforms. Officers are allowed a clothing allowance for the purchase of uniforms, but it doesn't go very far if there are a lot of them or if they change often.

Anyhow, that's where the "Pink & Green" uniform came in.

Under the new regulations that came in during the 1920s, the officer service coat was a dark green coat with an open collar. The trousers were khaki. In warm weather or warm regions, officers wore khakis like enlisted men, but unlike the enlisted men, they also were required to have a wool khaki uniform that had a wool khaki shirt, wool khaki trousers and a wool khaki service coat. That latter service coat was of a completely different pattern from the service coat for general use, oddly enough. Indeed, it's the pattern that was later adopted for general issue to all ranks. . .a trend that seems to repeat it self.

U.S. Army officers of World War Two wearing Pinks & Greens. The officer on the left is an Air Corps officer and is wearing his cap with the stiffner removed.

Making it a bit more confusing, the shirts that went with the new officers uniform varied from khaki, to dark green, to a sort of chocolate green. It's really difficult to tell when one was supported to be worn over another, and I suspect that it often varied by individual officer a fair amount.

This was all well in good in peace time, but during war time, it didn't work at all as the uniform was obviously unsuited for combat. Given that, in the year leading up to World War Two for the United States, the Army adopted an entire series of uniform additions or even new uniforms that ended up being the ones used in World War Two. When that occurred, the Service Uniform was relegated to being a dress uniform.

But not the full dress uniform, or the Dress Blue uniform. That uniform was always around, but it wasn't issued to enlisted men during the 1930s, or World War Two, as it was too expensive to do so. In 1938 it was redesigned to have an open collar and a white dress shirt. If that sounds familiar, that's because that's the dress uniform that has been in use in recent years.

U.S. Army general officers in Europe exhibiting the spectacular variance in semi dress uniforms at the end of the war. All of the officers depicted here wear the Eisenhower type jacket that Dwight Eisenhower caused to be introduced into service based upon his like of the British Pattern 39 combat jacket.***** From left to right in the back row, we see: (Stearley) Dark Green "Eisenhower Jacket" with garrison cap and khaki shirt and tie, (Vendenburg) Olive Drab Eisenhower jacket and wheelhouse cap with stiffner removed (common for Air Corps officers), (Smith) Eisenhower jacket worn by officer who had not afixed any decorations; (Weyland) Eisenhower jacket worn with green tie, (Nugent) Eisenhower jacket with wheelhouse cap with stiffener removed. Front row: (Simpon) Eisenhower jacket, (Patton) private purchase Eisnehower jacket cut from service jacket featuring brass service buttons with General Officer's service belt, uniform breeches and private purchase riding boots based on the Army pattern; (Spaatz) completely non regulation khaki colored Einenhower style jakcet with khaki wool trousers, (Eisenhower) dark green Eisehnower jacket with dress khaki wool trousers and private purchase shoes, (Bradley) Olive Drab Eisenhower jacket with OD wool trouers, (Hodges) Olive drab Eisenhower jacket and trousers with U.S. Army service shoes, (Gerow) Eisenhower jacket in olive drab shade with olive drab trousers and paratrooper boots.

After World War Two for some weird reason the Army decided that it had to adopt a new service, or in other words dress, uniform. This seems to have been based on the fact that after fighting a huge global war followed by a large war of peace (the Korean War) there were so many dress uniforms around that the Army felt that their status was diminished. That logic is fine, in so far as it goes, but it didn't seem to contemplate the Cold War, which would continue to bring millions of men into the service.

Walter Bedell Smith and Dwight Eisenhower, center, with Allied officers at the end of World War Two. Smith is wearing the Pink and Green service uniform, Eisenhower is wearing the jacket named after him in the Olive Drab shade and a dark green tie.

Be that as it may, that's what motivated the Army to adopt The Green Pickle Suit in 1957.

Eh?

Yes, that was the derisive name given by soldiers to the Army Service Uniform, now called the Army Green Uniform. that was adopted after the Korean War. The uniform, at first, featured a dark green service coat of the exact same pattern as the former officers wool khaki service coat mentioned above, and trousers of the same shade. Officers trousers featured a black stripe down the side, although officers didn't always buy trousers with that really ugly addition. Indeed, frequently they did not. Black shoes and a dark green wheelhouse cap and dark green flat cap finished the uniform. By dark green, we mean a sort of forest green. The shirt was khaki. The tie was dark green. There was no difference between officers and enlisted uniforms except as noted which was the first time that this had been the case since the 1920 with there being some actual distinctions between enlisted men and officers prior to then. The Army also adopted an optional khaki colored uniform for hot climates, phasing it out however in 1969.

As originally issued or purchased (by officers) the uniform featured dark green heavy wool coat and trousers which may explain why a tropical version in lighter wool was issued at the same time. As noted, the shirt was khaki and at the same time the Army had a semi dress uniform that was an evolution of the undress khaki uniform that had come in during the 1930s. This evolved however and starting in 1964 the green uniform started to feature an "all season" wool, which was the beginning of the end of its acceptable appearance. In 1979 the Army adopted a "mint" green shirt to go with the uniform that was hideous and hated by everyone who wore it and it started to phase out the semi dress khaki uniform. In 1990 it completed the uglification of the uniform by switching the already too light fabric to a poly/wool blend, just at the time that petroleum based clothing was solidly on its way out for good.

During the same period the Army reduced, then re-expanded, the headgear that went with the uniform. Every since the 1920s the Army had been issuing peaked or wheelhouse caps as well as garrison (overeseas) caps to be worn with the dress uniform or even with the service uniform. It continued to do this all the way through the Vietnam War, amazingly, as that made for a lot of headgear for troops who also had separate fatigue and combat uniforms. After the Vietnam War it stopped doing this and for a time just issued garrison caps, although it retained the wheelhouse cap as a private purchase item, but then in the late 1980s it adopted the black beret, which was a controversial move at the time.

The Green Pickle Suit was never fondly thought of by soldiers, who perhaps thought it, accurately, having a sad appearance in comparison with the Service Uniform that preceded it. Nonetheless, it lasted a really long time. Unfortunately, the quality of materials in it drastically declined during its service, going from a nice wool to a crappy wool poly blend. That last version looked bad due to the materials more than anything else, but at some point the Army decided to abandon it in favor of a blue dress uniform.

Dress Blues had come back into service for enlisted men in 1954, having ceased to be issued in the 1920s and as a practical matter not really having been issued since prior to World War One. Up until the abandonment of the Army Green Uniform for the blue uniform, it was an optional item for enlisted men. The basic pattern of the blue uniform had been adopted in 1938, and there was a rarely seen white uniform that existed at the same time and in fact which survived at least into the 1990s.

The problem there is that the blue uniform, when modified and adopted for general use, was made of the same ultra crappy looking materials. So it looked pretty darn bad as well. I'll not go into it, but a blue dress uniform of wool/ploy craptacular looks craptacular.

We'll note, fwiw, that this entire time the Marines stuck with a uniform, a good looking one, that they'd adopted in the 1920s as well but which was less modified in form from their World War One era one. Everyone always remarks how good looking that uniform is.

Hmmm. . . .

Well, anyhow, after years and years being afflicted with lousy looking dress uniforms, the Army has decided to introduce the Army Greens Uniform, which is the old Pink & Green uniform, sort of.

Here's an Army summation of it:

Army Greens Uniform

Provided by PEO Soldier Tuesday, December 11, 2018

What is it?

The U.S. Army is adopting the Army Greens as its new service uniform, based on the iconic "pink and green" uniform worn during the World War II. This will be the everyday service uniform starting in 2020, and it will reflect the professionalism of the Soldier.

The Army Greens Uniform will include khaki pants and brown leather oxfords for both men and women, with women having the option to wear a pencil skirt and pumps instead. There will be a leather bomber jacket as an outerwear option.**

The Army Blues Uniform will return to its role as a formal dress uniform, and the Army Combat Uniform also known as the Operational Camouflage Pattern, or OCP will remain the duty/field uniform.

What are the current and past efforts of the Army?

In March 2017, Program Executive Office Soldier (PEO Soldier), under direction from the Chief of Staff of the Army, prepared a "Greens" Uniform demonstration and options to support the decision-making process. Extensive polling data showed overwhelming support for this uniform.

On Veterans Day, 2018, the Army announced the new uniform, which will be made in the U.S., and have no additional cost to the American taxpayer. This uniform will be constructed of high-quality fabrics and tailored for each Soldier. This will be cost-neutral and covered under enlisted Soldiers' annual clothing allowance. The new uniform and associated materials will comply with all Berry Amendment statutory requirements for Clothing and Textiles.

What continued efforts does the Army have planned?

The Army will conduct a Limited User Evaluation (LUE), using Soldiers that interact with the public. These Soldiers will wear the new uniform for a few months and then provide feedback for possible last-minute changes to the final design. The mandatory wear date for all Soldiers will be 2028.

Why is this important to the Army?

The reintroduction of this uniform is an effort to create a deeper understanding of, and connection to, the Army in communities where awareness of the Total Army needs to increase.

The Army believes this high-quality uniform will instill pride, bolster recruiting and enhance readiness.

Loyalty, Duty, Respect, Selfless Service, Honor, Integrity and Personal Courage are core Army Values, and the new uniform is at the center of demonstrating Soldiers' values, professionalism and accountability to each other and the American people.

The Army Greens will be worn by America's next Greatest Generation as they develop into the smart, thoughtful and innovative leaders of character outlined in the Army Vision.

Now, the old uniform, and by extension this one, is much, much better looking than the old Green Pickle Suit.

But something just seems wrong. What is it?

Well, for one thing, the Army isn't adopting the 1926 to 1957 dress uniform. . . it's adopting the dress uniform of that period that was issued to officers only.

I don't mean to sound chauvinistic at all. I was an enlisted man, not an officer, but adopting the officers uniform of that period somehow smacks of grade inflation, if you will. The Army has already been suffering from something like this anyhow since World War Two or at least World War One, and this really seems an expression of that.

Going into World War One the Army issued but single medal, the Congressional Medal of Honor. During the war, in recognition of what a big event it was, the Army introduced wound stripes, overseas bars and in 1918 the Silver Star. During World War Two additional awards were added, including the Bronze Star, the Combat Infantryman's Badge, the Expert Infantryman's Badge, etc. I'm not saying that any of this was bad by any means but it reflects a definite trend.

Coming out of World War Two a lot of soldiers now had a variety of awards in addition to those that had been authorized earlier reflecting campaigns and other decorations. This has continued on to the point now where a career soldier has a shocking number of awards compared to his World War Two colleagues. The black beret itself is also an example of this as originally the only American soldiers who wore the berets of any color were the post war Special Forces, who were even nicknamed for their beret. Black berets came in unofficially for Rangers in Vietnam during that war and then were taken up by tankers, mimicking the British (who had earlier mimicked the Germans) in the 1970s. That was put to an end but the mass issuance of black berets offended both and particularly offended the Rangers who soon acquired a tan beret, somewhat recalling the general issue color that had been adopted by the British during World War Two. Now the Airborne also has its own color, maroon, also recalling the World War Two British issuance.

The point is that if the Army really wanted to recall the heroic service of American troops in World War Two, it ought to just go back to the pattern of dress that existed in 1939. It was a good uniform and it looks right. Most sergeants don't want to look like they're pretending to be an officer in the first place.

And frankly another thing that doesn't look quite right is the uniform itself. For most of the officers who wore it, in its incredible assortment of varieties, it featured a stiff wheelhouse cap and an officers overseas cap. The Army here is adopting the wheelhouse cap with the stiffner removed, which looks sharp but which was an Army Air Force thing that went on to be continued by at least the first USAF dress uniforms. After the separation of the Air Force from the Army in the 1940s the Army made fun of the early dress uniform of the Air Force by calling it a "bus driver's uniform, but now the Air Force will have legitimate reasons to be miffed at the Army, particularly as the Army is also going to readopt the A2 flight jacket.******

Beyond that, one thing that the adoption of the uniform really glaringly points out is that World War Two, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and even our current wars, were men's wars, war being and remaining a traditional role of men. There's something almost shocking about seeing the pink & green uniform altered to contemplate pregnancy in a way that the same for the Army Green Uniform or the blue uniform was not surprising to the eye. Or maybe its because there was a period female pink & green uniform that's obviously not been adopted, and I don't blame them for that, which causes a bit of mind bending in the historic throwback category. The updating by the British of their service uniform, which they've retained as a dress uniform for the entire period since World War Two, for women looks absolutely correct, because of its long usage, the same just isn't true of the female variant of the pink & green uniform which hasn't been.

And maybe you can't recapture past glory. You can recall it, but World War Two and the Korean War are over. Readopting the uniform of that period, after so many years have gone by, seems odd. It's much like watching the British celebrate their victories and triumphs of the Second World War. It's poignant, but it seems like maybe its so focused on as nothing very good has happened to them since.

Not that the Army doesn't need a new uniform, although its not replacing the Dress Blue uniform, only augmenting it for daily wear. It does. But something here just isn't working.

_________________________________________________________________________________

*Khaki is a confused term in American usage. The term was a Hindi one that was picked up by the British with the apparent meaning of "dust". But in British military use it meant a color much like the American Olive Drab.

**The U.S. experimented with uniforms a great deal from 1890 to 1910 or so and there were a lot of changes and varieties of uniforms including some that retained blue for awhile. White is clearly not a suitable uniform for an Army in the field in the smokeless powder era, but it took the Army awhile to catch on to that.

***I don't know what caused the Army to switch from khaki for hot weather to a light olive uniform for the same, but it did.

Regarding the pants, the Army issued breeches and not trousers, having gone to that some time prior. Breeches are associated with equestrians today and because the Army was so horse dependant its not surprising that it would choose breeches as its pants. having said that, not even cavalrymen were issued breeches in the U.S. Army up until the 1890s when the uniform changes started to come in.

Breeches were an extremely common military pant at the time and while they look very awkward now, they served a real purpose. Most armies, the United States Army included, did not issue high boots to infantrymen. As the Army always wanted trousers sealed up for protection from vegetation and insects that meant this had to be done with leggings or puttees. Both of these items are very uncomfortable with trousers but less so with breeches. It's notable that when the Army abandoned breeches for trousers in 1939, save for mounted men, leggings were phased out within a few years thereafter.

****The actual field uniform at the time of the war with Spain was really in a state of flux and most soldiers deployed to Cuba wearing blue wool shirts, cotton duck stable trousers, and cotton duck stable jackets. The stable uniform by that time was died a color that resembles that of the current Carhartt cotton duck. Because of the heat, solders fought stripped down and therefore hardly ever wore the jacket.

The Army had just adopted a new service uniform at the time, however, and the soldiers should have been issued khaki breeches, blue shirts, and a khaki service coat. Most were after they returned to the United States.

*****So I don't go down too many rabbit holes, I'm not going to deal with uniforms that are sort of dead ends in our discussion here. But the Eisenhower jacket came about as Dwight Eisenhower was really impressed with the British Pattern 1939 battle dress, which featured an incredibly high wasted pair of baggy trousers and a short court. His influence caused the short coat to be adopted as a uniform item in the thought that it would serve all purposes, just like it did for the British, pretty much.

Polish volunteers in British battle dress during World War Two.

The problem was that the ship had sailed on that type of uniform already as the Army had adopted the M1943 field jacket. The M1943 field jacket, originally designed for paratroopers, would revolutionize military uniforms in the west and it only recently ceased to be issued, in its modified M-60 pattern, in the U.S. Military (but can still be worn as a private purchase item). After that, there was no way that the Eisenhower jacket was going anywhere as a field uniform.

Contrary to common belief, it didn't really go anywhere as a general issue item during World War Two, but officers started to acquire them ahead of the logistics system, and it became a common officer semi dress item by the end of the war. Shortly after the war the supply system caught up with the average soldier and it became very widely issued. This immediate post war issuance caused the Eisenhower jacket to be associated with the World War Two soldiers, as in the immediate peace time conditions it was a more comfortable item than the Service Uniform, but it never saw field use with the U.S. Army. It was quite popular through the entire period it was issued, however, and was adopted in blue by the USAF. It started to be phased out in the 1950s but servicemen who had acquired one before that were allowed to wear them for a long time, and they accordingly became a coveted item.

When the Army recently decided to adopt the Pink & Green uniform as a current dress uniform, it considered reintroducing the Eisenhower jacket but decided not to, perhaps because of a bad decision it made that's address in a footnote below.

******By which the Army means the A2 flight jacket, which was originally introduced for airmen and which is a current semi dress item for U.S. Air Force officers. The similar Navy pattern of flight jacket from World War Two remains a semi dress item for flyers in the Navy. This will be hugely unpopular with the Air Force and it should be.

American fighter pilots of the 332 Fighter Group being issued escape kits in Italy, 1945. These African American pilots are wearing a mix of uniforms, probably reflecting their length in time of service. The pilot on the left is wearing the classic A2 Flight Jacket with a flight suit underneath it. He's also wearing a wheelhouse cap with the stiffner removed. A pilot immediately behind him has the plastic rain cover on the same type of cap. The other two pilots in the photo are wearing later pattern cloth flight jackets that came into service during World War Two. One wears a garrison cap. One is carrying a M1911 pistol in a shoulder holster. The pilot on the left appears to be carrying one as well that he has not yet fastened. The seated lieutenant isn't an airman and wears a M1943 field jacket with a garrison cap, an allowable practice at the time. He also has his watch on upside down, a practice common to World War Two era combat troops and sailors. An airman in the background wears the sheepskin aviator's cap.

Tuesday, September 11, 2018

The American Serviceman During World War One: They were older than you think.

Or at least some of them were.

Dan Daly being awarded a French decoration during World War One. Daly was born in 1873 and had entered the Marine Corps during the Spanish American War in 1899, at which time he was 26 years old. He won his first Medal of Honor during the Boxer Rebellion. He would have been 45 years old at the time he won his second Medal of Honor during World War One. He'd serve on until age 56 and then retire, dying at age 63 in 1937. In some ways, Daly is emblematic of the NCO core of the time.

It's really common to read the statement about all soldiers being "young" during World War One, and certainly there were a lot of young soldiers who fought in the Great War. But they may not have been as uniformly young as a person might assume.

Let's start with a few facts about the armed forces of the United States during the second decade of the 20th Century.

The service offered retirement, however, to an enlisted man at the time who had served for 30 years. The period and system was similar for officers. Retirement after 30 years was at 75% of base pay, not a bad retirement for men, and they were all men, who were used to their existing level of pay.

To understand the impact of this, you next have to consider that the enlistment age for military service had been higher than it is today until just before World War One. In 1875 Congress had acted to pass the following provisions regarding military enlistment in the Army:

Sec. 1116. Recruits enlisting in the Army must be effective and able-bodied men, and between the ages of sixteen and thirty-five years, at the time of their enlistment. This limitation as to age shall not apply to soldiers re-enlisting.

Sec. 1117. No person under the age of twenty-one years shall be enlisted or mustered into the military service of the United States without the written consent of his parents or guardians: Provided, That such minor has such parents or guardians entitled to his custody and control.

Sec. 1118. No minor under the age of sixteen years … shall be enlisted or mustered into the military service.

So enlistment was allowed down to age sixteen, but only with parents permission. And enlistment was allowed up to age thirty five.

In 1899, in the wake of the Spanish American War, Congress changed Sec 1116 however to provide that you had to be eighteen years to enlist, and that still required parental approval. It wasn't until 1916 that Congress changed the statutes so that parental approval was no longer required for those eighteen years of age.

If this seems odd, it frankly fit the concepts of adulthood at the time, and it oddly squares with the current psychological concepts of when somebody is fully adult. At the time, and we've addressed this elsewhere, most men lived at home until married and even though many men left home for work prior to twenty years of age, many did not and lived at home. Barring enlistment under your own volition until age twenty-one made sense, just as originally allowing enlistment down to age sixteen under some circumstances did as well.

Put in context, therefore, most soldiers who had served long enough to retire were in their early 50s. They had to retire at age 64, which was the maximum age a serving soldier could be at the time.

This was changed during World War Two to expressly try to weed out older men, particularly officers, who were regarded as no longer sufficiently mentally flexible for modern warfare. But that was to come later. During World War One the 20 year retirement period for early retirement was in the future. Barring injury, career soldiers had to serve 30 years in order to retire or make it to 40 years to retire on full pay.

That meant, therefore, that for soldiers who had enough time in to retire in the year we've been looking at, 1918, had entered the Army in 1888.

But another way, that means career soldiers who were eligible to retire had entered the Army prior to the Battle of Wounded Knee, which is generally regarded as the last significant battle of the Indian Wars (it's not the last battle).

Artillerymen of Wounded Knee, 1890.

By way of some examples, John Pershing, commander of the AEF, had entered the Army after attending West Point in 1886. Douglas MacArthur, who was considerably younger, had entered the Army in 1903.

Captain John J. Pershing in 1902. At this point he had already been in the Army for eighteen years.

Now, as we've already discussed, the size of the Army prior to World War One was tiny, so this only applies to a small number of the men who served in the service in the Great War (although we must also consider the Navy and the Marines in this as well. But it is significant.

U.S. officers in Cuba during the Spanish American War, including Dr. Leonard Wood, in a combat command, second from right (Theodore Roosevelt far right). Wood would later be the military governor of Cuba and was widely regarded as the logical commander for the AEF. His association with Roosevelt certainly operated against that. Wood had entered the Army as a contract surgeon in 1886, which was the norm for military surgeon's at the time, and had won the Medal of Honor for carrying dispatches 100 miles in the campaign against Geronimo.

If we look at the National Guard the situation gets much murkier. There was no retirement for National Guardsmen at all until just prior to World War Two and, therefore, there was little reason to stay in the National Guard for thirty years, although many did. And Guard units were much looser in adherence to age limits, so they not infrequently allowed enlistment of underage soldiers all the way up until just before World War Two. So that changes our consideration quite a bit, as the National Guard was a significant part of the Army during the war.

Hugh Scott, who was Army Chief of Staff at the start of World War One and who had to retire upon reaching age 64. He was born in 1850 and had entered the Army in June 1876, meaning that he had actually entered the Army just before the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

So were draftees. Conscription brought huge numbers of men into the service during the Great War, although only to the Army. The other services did not draw conscripts. The original conscription ages were from age 21 to 31. This was changed later to age 18 to 45. Voluntary enlistment ages comported in expanding upwards.

Now, these points can be overdone. Most men who joined the Army as enlisted men did not stay in it, serving a single enlistment. They may have been older, on average, than men who enlisted after the enlistment age became 18, but just like those men now, they usually didn't make a career of it. But at the same time, the Army was smaller then and the up or out system that exists now, did not exist then except, to a limited extent, for officers.

And most men who came into the U.S. Army, Navy and Marine Corps during World War One did so solely for the duration of the war. They had no intent to remain in the service at all. And those who came in via the draft, and that was the large majority, were scaled towards the lower age, intentionally, rather than the higher age. So most U.S. servicemen during World War One were undoubtedly in their twenties.

Still, that's significant. . . and not only for WWI but for later U.S. wars as well. Contrary to widely held belief, the U.S. military isn't usually made up of "kids". Teenage combatants have certainly existed, but they are not and never have been the rule.

For what its worth, the Army has in recent years nearly returned to the WWI, and WWII, upper age limits for enlistment and in some ways we see the age story of a century ago repeating. The upper age limit for the Army is now 42, two years younger than what the Army asked for, which was age 44. That's fairly amazing, but it shows that the average condition of people in their 40s is often better than it was in prior decades when chronic injuries took their toll. Indeed, while we have pointed out that people really aren't living longer than they used to, as is so often claimed, they are often quite a bit healthier than they used to be due to medical advances and other factors.

Now, these points can be overdone. Most men who joined the Army as enlisted men did not stay in it, serving a single enlistment. They may have been older, on average, than men who enlisted after the enlistment age became 18, but just like those men now, they usually didn't make a career of it. But at the same time, the Army was smaller then and the up or out system that exists now, did not exist then except, to a limited extent, for officers.

And most men who came into the U.S. Army, Navy and Marine Corps during World War One did so solely for the duration of the war. They had no intent to remain in the service at all. And those who came in via the draft, and that was the large majority, were scaled towards the lower age, intentionally, rather than the higher age. So most U.S. servicemen during World War One were undoubtedly in their twenties.

Still, that's significant. . . and not only for WWI but for later U.S. wars as well. Contrary to widely held belief, the U.S. military isn't usually made up of "kids". Teenage combatants have certainly existed, but they are not and never have been the rule.

For what its worth, the Army has in recent years nearly returned to the WWI, and WWII, upper age limits for enlistment and in some ways we see the age story of a century ago repeating. The upper age limit for the Army is now 42, two years younger than what the Army asked for, which was age 44. That's fairly amazing, but it shows that the average condition of people in their 40s is often better than it was in prior decades when chronic injuries took their toll. Indeed, while we have pointed out that people really aren't living longer than they used to, as is so often claimed, they are often quite a bit healthier than they used to be due to medical advances and other factors.

Thursday, July 5, 2018

The United States Marine Corps in World War One (and before, and beyond).

It was the Battle of Belleau Wood that gave us the modern Marine Corps.

Just the other day I posted an item on the U.S. Second Division during World War One.

Now, there has been a United States Marine Corps since 1775, as somebody will surely point out if I do not.* The Marine Corps claims a "birthday" only five month junior to that of the U.S. Army's, although the dates of those creations are a bit dubious in that neither organization has had a continual existence since that time. The National Guard's is actually older, tracing back to 1636 in the form of colonial militias. But whatever the history of those creations may be, the early Marines are not the same force that exists today in terms of its role and combat abilities.

To look at that force, you have to go back to September 21, 1917, when the 2nd Division was constituted.

The military establishment of the US was so small that when the government went to form divisions for service in France it was faced with a daunting problem, and massive internal strife. A lot of U.S. Army officers regarded the war as their show and their show alone. The Navy anticipated that the American role would really be on the North Atlantic and the concept of even forming a significant ground force in time to fight in France was an utter joke. That joke became no laughing matter, however, when the Allies sent over delegations to the United States and the country learned, really for the first time, that in spite of Allied offensives in 1917, the Allies were on the verge of collapse and defeat. When this became apparent, punctuated as it soon was by the Russian Revolution, it became rapidly obvious that the Army was going to have to be increased enormously in size and sent to France.

The Army, however, had only enough men to form a few divisions. And not even that many. And on top of it, Army units were already stationed around the globe in places that the Army could not readily abandon. Army units in the Philippines really couldn't abandon that mission. Some troops had to remain in Hawaii. The Canal Zone had to be garrisoned, particularly during wartime. And the Mexican border, while no longer looking like it was about to become the front-line in a war with Mexico at any moment, was still a long frontier that had to be manned and on which fighting continued to occur. The US, for that matter, still had troops in China (including Marines).

And in spite of these commitments, on April 6, 1917, when the United States declared war on Germany, it had just 127,151 men in the standing U.S. Army. An additional 181,620 were in the National Guard. Of that 127,151 there were a not negligible number that would have to remain overseas right where they were. The 181,620 men in the National Guard had all been recently hardened by 1916 and 1917 border service, but even at that there were men who were not fit for continued service.

A daunting problem.

The Marines, part of the Navy, had just under 14,000 men, however. Not a large number. . . but one that was significant in context.

They weren't, however, the force we imagine now. They became that because of World War One.

The United States Marine Corps was modeled on the British Marines at the time of their formation. Marines, in that context, were "soldiers of the sea", as the phrase goes, but their role was very ship oriented. Marines in naval engagements at that time, the 1770s, filled a role that's very well depicted in the film Master and Commander. They formed a trained body of musket infantry for when ships were close to each other, with their targets being the sailors on the opposing ships. They were part of the boarding parties, when that occurred. And they formed an armed body to go ashore in small units when that was called for, which it frequently was. It was not as if, after all, the Navy could depend upon the Army to provide infantrymen in small units for ships that were at sea for months, or in some cases even years. A ship's commander, who had almost complete operational independence in those days, needed a body of infantrymen for any contingency that required putting men ashore, and it did fairly frequently.

Continental Marines going ashore during the Battle of Nassau, March 1776. They likely weren't this well dressed in reality.

Marines also formed the commander's police force against his own crew, something we don't think of much now but which was necessary then. Sailors in 18th and early 19th Century navies were incredibly tough and independent bodies of men whose allegiances were often passing. Unlike later navies of the steel and steam age, in the age of sail sailors were uniformly of that odd port culture that existed around the globe. Most navies included men who were drawn from all over. The United States Navy, as an example, was integrated at the time in the enlisted ranks, and even slightly in the officer ranks, and included men who hailed from other countries as well as from American ports. All that mean that experienced sailors, who were in demand for their skills, and who tended to regards ports as homes rather than nations, were liable to become disenchanted with military service and cause problems, even serious problems, for their officers.

Marines from every nation formed the officers bulwark against that. Marine units were small and cohesive and kept apart from a ship's crew as much as possible. In the case of the early United States Marines, the service was the most segregated in the regular establishment (the Navy was not segregated, as noted, and while the Army was, there were always odd exceptions in the Army). That's not pleasant to contemplate, but it is the case. The creators of the early Marine Corps wanted a racially cohesive separate body on teh theory that if they had to use it against the crew this mean that they were that much more likely to be loyal to their officers than to anyone else.

And so the Marines were first formed in 1775. They were disestablished after the Revolution. But they were shortly brought back in. And they've been in existence ever since.

U.S. Marines, 1864.

Be that as it may, however, up until the Spanish American War their role remained the traditional one. You can find exceptions, they were at Harper's Ferry for example, but they truly are exceptions. They filled the role that they were first created to fill.

Starting around the turn of the prior century, however, and a little before that, that began to slowly evolve. As the steam and steel navy came in, the ability to project power, and to stay in touch with the US, increased. The Navy had always been used that way to some extent, but you no longer saw individual ships sail off to distant lands and, frankly, do something weird. Ship commanders didn't engage in local punitive expeditions in Korea anymore, for example, or get into naval battles in Japanese rivers.

But the Navy did start flexing American muscle in the Gulf.

Marines with new khaki uniforms. These had probably just been issued prior to this 1898 photograph. Prior to this they would have worn blue uniforms much like the Army had, with this pattern of campaign hat which the Army also wore. Bending up the brims of the hats was particularly common for Marines. As these Marines are all fairly young, there's a good chance that at least one of them would have still been in service during World War One, which if true would mean that he would likely have seen combat all over the globe by that time.

The change from sail to steam, and from wood to steel, had an impact on the Marine Corps that would be only slightly less substantial than the impact of the same on the Navy, and indeed it was because of the impact on the Navy that the role of the Marine Corps significantly changed. Even in the waning days of sail it had often been the case that naval vessels were dispatched to far distant regions of the globe and basically left to the complete discretion of their commanders. With steam, however, vessels moved more rapidly, and less independently, and greater operational control came in. By the same token, however the ability to project power with a navy hugely increased, but not int he same fashion for every naval power.

For nations with empires, like the United Kingdom, the role of the navy greatly expanded, but the role of their marines did not. This is at least in part because if colonial nations needed to project ground power, they usually had it nearby or at least within a transportable distance. Contrary to what some might expect, the British Army prior to World War One was quite small, but it was widely dispersed around the globe. The French army, in contrast, was large, but it also had a global deployment. The U.S. Army, up until the Spanish American War, was deployed entirely in the United States and its few overseas territories as well as . Even after the Spanish American War this did not change greatly, although it did change a bit, particularly in regards to the Philippines, which the US found itself engaged in a guerilla war and occupation in, following its capture during that war.

So, given this, the Marines started to fill another role. With the only real way for the US to project power around the globe, the Marines, part of the Navy, started to become the US's rapid reaction, small scale, intervention force. They became particularly active in deploying throughout the Caribbean Basin and Central American whenever the US decided it needed to show the flag, which it quite often felt it needed to. They became so associated with intervening in Central America in this period, and became such effective fighters in that context, that they remain legendary as a nearly unbeatable force in that region. But it even meant that part of the Marine Corps would find itself more or less permanently stationed in Asia, in China specifically, following the Boxer Rebellion.

Just prior to World War One this role expanded out to include intervention in the Mexican Revolution prior to the Army doing the same in the Punitive Expedition. In 1914 the Marines were put ashore in Vera Cruz, Mexico, and occupied the town in a direct, but limited, intervention in the Mexican War.

_________________________________________________________________________________

*The 1775 body was actually the Continental Marines. The United States Marine Corps did not come into existence, under that name, until 1798, at which time, which re established a corps of marines.

For nations with empires, like the United Kingdom, the role of the navy greatly expanded, but the role of their marines did not. This is at least in part because if colonial nations needed to project ground power, they usually had it nearby or at least within a transportable distance. Contrary to what some might expect, the British Army prior to World War One was quite small, but it was widely dispersed around the globe. The French army, in contrast, was large, but it also had a global deployment. The U.S. Army, up until the Spanish American War, was deployed entirely in the United States and its few overseas territories as well as . Even after the Spanish American War this did not change greatly, although it did change a bit, particularly in regards to the Philippines, which the US found itself engaged in a guerilla war and occupation in, following its capture during that war.

So, given this, the Marines started to fill another role. With the only real way for the US to project power around the globe, the Marines, part of the Navy, started to become the US's rapid reaction, small scale, intervention force. They became particularly active in deploying throughout the Caribbean Basin and Central American whenever the US decided it needed to show the flag, which it quite often felt it needed to. They became so associated with intervening in Central America in this period, and became such effective fighters in that context, that they remain legendary as a nearly unbeatable force in that region. But it even meant that part of the Marine Corps would find itself more or less permanently stationed in Asia, in China specifically, following the Boxer Rebellion.

Marines in China, 1900.

Deployment to China was a groundbreaking change in the role of the Marines. For the first time they were assigned to an open ended land based mission that separated them from ships on a continual basis and guaranteed that they'd be seeing land based action continually. The Army actually shared the role, something that is commonly missed, and so this also formed the first instance in which the role of the Marines came to over shawdow that of the Army even where they were both present.

The Banana Wars, a series of Central American and Caribbean interventions, would really cement that image. These interventions, which commenced following the Spanish American War and went on into the early 1930s, meant that joining the Marines meant you would see combat.

Marines boarding for deployment in Nicaragua in 1912.

All but forgotten now in the United States, and bitterly remembered in Central America, the wars were US efforts to influence the affairs of developing Central American nations. The wars also had a distinctive economic aspect to them. Navy and Marine Corps affairs, the Army was left out of them.

Sailors in Nicaragua in 1912.

These interventions were numerous, and even detailing them now would make for a much more expansive post than anyone would be interested in reading. Suffice it to say, however, their continual nature is impressive.

Marines in Haiti, 1915.

Just prior to World War One this role expanded out to include intervention in the Mexican Revolution prior to the Army doing the same in the Punitive Expedition. In 1914 the Marines were put ashore in Vera Cruz, Mexico, and occupied the town in a direct, but limited, intervention in the Mexican War.

Marines and Sailor raising U.S. flag at Vera Cruz, 1914.

So when the United States went to form divisions of regular soldiers to be deployed to France, taking Marines and adding them to the 2nd Division made a lot of sense. They were extremely tough and very experienced infantry.

And they served in that role extremely well. An experienced body of men, they more than lived up tot their reputation.

The Marines became an integral part of the 2nd Division during World War One, even contributing to the division two of its divisional commanding officers. It came out of World War One with its reputation as a potent ground force assured.

After the war, the Marine Corps returned to its former role, but its reputation was for ever changed. While the Marines continued on in the Banana Wars and in China, they also began to plan for the future.

Marines in Nicaragua, 1932.

And planning for the future, in the eyes of the Marines, meant building and expanding on the ground role they'd played in World War One. That meant, in their view, developing a seaborne landing capacity that was nearly independent in some ways from the Navy, although obviously not completely. Between World War One and World War Two, the Marines, with the cooperation of the Navy, took amphibious landing to a new height, making it nearly a unique American deal. The lessons and equipment they developed in this period would end up being used by the Army as well when World War Two came to include the United States and, ironically, the largest amphibious landing of all time, Operation Overlord, would not include a single landing Marine. But the war in the Pacific certainly did, and in a major way.

Marines fighting on Iwo Jima during World War Two.

It was World War Two, of course, that gave us the fully modern Marine Corps. Ironically, perhaps, the Marines of World War Two were distinct from that of World War One in that by the wars end most of them were wartime volunteers, not the salty professionals that made up the Great War Marines. They were molded around that example, however, and by the wars end the wartime Marines closely resembled that of the "Old Breed" that made up the core of the pre war Marine Corps.

Following World War Two the Marine Corps refused to accept what the Army, Navy and Air Force did and assume that all future wars would be nuclear wars with little ground action. They couldn't accept that, as that would mean no future for the Marine Corps. They continued to hone their seaborne abilities and expanded very early to include airborne assault. Their saving example at Inchon during the Korean War guaranteed that they'd have a prime place in the post World War Two military, which they've preserved ever since.

The soon to be killed Lieutenant Baldomero Lopez scaling the seawall at Inchon. Mere minutes after this photo was taken, Lopez intentionally dropped on a live grenade to save fellow Marines.

_________________________________________________________________________________

*The 1775 body was actually the Continental Marines. The United States Marine Corps did not come into existence, under that name, until 1798, at which time, which re established a corps of marines.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)