Recently, on our companion site

Holscher's Hub, I posted two photo threads about Post World War One homesteads. Those posts are

here and

here.

People commonly think of homesteading in the 19th Century context, often having a really romantic concept of it. What few realize is that the peak year for homesteading in the United States was 1919.

That's right, 1919.

Homesteading itself carried on until the Taylor Grazing Act ended it in 1934 in the lower 48 states. It carried on in Alaska for longer than that, under the Federal law, and still exists under Alaska's state law, although its really a different type of homesteading than existed in the lower 48. There were some exceptions, which I'm unclear on, that opened lands back up after World War Two, on sort of a GI Bill for the agriculturally minded type of concept, but the enthusiasm for it was apparently limited. In Canada I think that homesteading may have continued on into the 1950s.

But it was World War One that caused the last big boom in U.S. homesteading, and it was they year immediately following the war, which was also the last year that farmers had economic parity with urban U.S. populations, that saw the greatest amount of homesteading. And it was a homesteading boom, in some ways, that was uniquely 20th Century in character.

Truth be known, homesteading was never really viewed the way that we have viewed it in the post homesteading era. Our modern romantic view of it is unique to the post World War Two industrial era in some ways. There's always been a strain of romanticism attached to it, to be sure, because it fit in with the Frontier character of the country that existed in the 18th and 19th Centuries. And it also tended to define, as we've forgotten in modern times, a real difference between Americans and Europeans. American farmers, which meant most of the population, could own land and do well by it. European farmers, which meant most of the population, often did not. Europe became an urban center earlier than the US in part for that reason, as the landless could have a better chance of owning something of their own off the farms, and getting a farm of your own was extremely difficult, if not impossible, in most European nations if you were not born with ownership of one. Indeed, the desire for land fueled immigration to the United States, Canada, Mexico, and various other areas that Europeans colonized, far more than any other source. We may imagine that immigration was mostly the tired, hungry, and downtrodden, and of course it was. But land hungry made up a big percentage of immigrants as well.

19th Century homesteading, even at the time, was seen as sort of a transitory affair, and you can find a lot of contemporary articles about farmers being the vanguards of civilization. This is particularly true of stock raising homesteaders, i.e., ranchers, who were seen as a pioneering, but temporary, force, except by themselves. Theodore Roosevelt, himself a rancher, commented in one of his late 19th Century articles about how herds of stock inevitably gave way to the plow, comparing ranchers to Indians, which meant that even he saw his ranching activities as doomed by history. If so, he misjudged the progress of the plow. Even as late as the early 20th Century, however, people seriously believed that "rain follows the plow." It doesn't.

20th Century homesteading was something else, however. The homesteading boom of the teens was fueled by the globalization of the grain market, and a unique but temporary boost in the market and a unique, but temporary, increase in the amount of annual rainfall. All of these combined created the conditions which allowed for a spike in homesteading, followed by an inevitable collapse in the agricultural sector.

The unique and temporary boost in the market was caused by warfare. The second decade of the 20th Century was one of the most violent of the 20th or the 19th Centuries, and even the horror of World War One did not occur in a vacuum. European wars started in the teens with a series of Balkan Wars; wars limited to the Balkans and Turkey, but which presaged the international conditions which would expand past that region and into Europe in general. The Mexican Revolution broke out south of the border in 1910, and was really rolling by 1911. But it was World War One that really strained the global agricultural system to the limit.

In the abstract, how a war could do that is sometimes difficult to understand, in our modern, overabundant, era. But the reasons are fairly plain. The war put millions of men into the field, in harsh conditions (the war was accompanied by unusually harsh weather in Europe) where their caloric requirements were high. Additionally, and now much more difficult to appreciate, the war also put millions of horses into the military service with a high caloric requirement as well. For the men, their needs were met with meat and grains, and for the horses, grains and fodder. The requirements were vast. And this was compounded by the fact that animal production also provided the leather and wool upon which the armies also depended.

Not only, however, were the requirements vast, but the labor to do the work was now serving in various armies. Not only did the war require a lot of agricultural production, but it required the men who were doing it, in large part, to serve in the armies. This caused a shortage of farmers, just as there was a great need for them. And not only was there a shortage of farmers, but of farm animals as well, as agriculture remained mostly horse driven.

War time poster encouraging the saving of wheat, based on a famous contemporary photograph of women serving as the power for an implement, in the absence of draft animals, in France.

Farm labor shortages were partially made up by pressing women into service as farmers, everywhere. There's a very common myth that women entered the workplace during World War Two, but it simply isn't true, or even close to true (we'll address this in an upcoming post). Women entered the factory and fields in massive numbers during World War One. Their role in food production became a national campaign in most Allied nations, where there were official efforts to put them into the field.

American Women's Land Army poster.

U.S. poster encouraging men below the age the Army was then seeking to serve on farms. In short order, the Army would be taking me down to 18 years of age.

The American appeal was more rustic than the Canadian one, which made a martial appeal to young men to serve on the farms, relating that service to military service.

Resources became so tight that, even though rationing was never required on a national level in the United States (at least one state rationed, however) there was also an official campaign to encourage food conservation, and even conservation of some particular foods, so that more was available to feed the troops.

Canadian wartime poster encouraging consumers to switch to other foods to save food for the armies.

The war also had the impact of physically taking millions of acres of land directly out of production. Not everything can be produced everywhere, which is fairly obvious. Grains remain the staple of life in modern times just as much as they did in ancient, and this is particularly true in the case of grains. Grain can be grown, and is grown, in many regions, but large scale export grain crops are not. Grain production has greatly increased since World War One, but something that may not be readily apparent is that grain growing regions have expanded as well.

During the First World War era, grains were widely grown in Europe, North America, Argentina and Russia. Much of the European production, however, was part of a regional market. Italy, for example, has always been a grain growing region, but we tend not to think of it as a grain exporting region (although it actually is to some extent). Of these regions, only two remained unspoiled by the war that being Argentina and North America. Russia, one of the worlds most significant grain producing regions (well, the Ukraine actually) was taken completely out of the picture by the disaster of the war, which was followed immediately by the Russian Civil War.

This is also true of livestock production. Horses, a critical item for every army, were so much in demand that Europe was basically stripped of them, nearly causing the extinction of one breed, the Irish Draught. The United Kingdom, a major horse user, had always replied on imports for military horses and had worried about the supply pre-war, and now found itself fighting with an ally that had the same concern. The large horse producing regions of the planet, North America, Australia and, at that time, Argentina remained relatively unscathed. This was true for beef cattle production as well. It was less true of wool production, which was a critical fiber in the war, and the United Kingdom itself was a significant producer.

Wartime Canadian poster appealing to economic opportunism and patriotism.

While all of this was a human disaster, it was an agricultural opportunity of unprecedented scale. A vast demand for agricultural products was created, and in certain regions, the means to exploit it existed. And not only did the means exist, in the United States the government was encouraging it. The US government encouraged homesteading, particularly for grain production, as if the boom would never end. And, as the Homestead Act remained in effect, and as the weather was unusually wet and therefore farming easier than usual, a land rush was soon on.

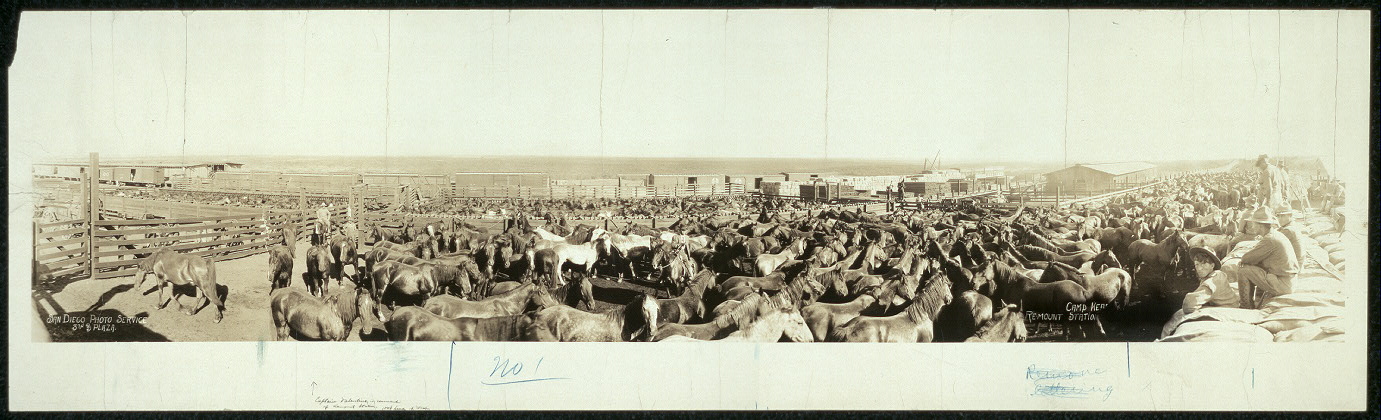

And the boom was experienced in other areas of the agricultural sector as well. Horse ranching went into a massive boom in the West, starting just as soon as British and French remount agents started scouring the US and Canada for horses; a need which could never be fully met, in spite of a global effort. Soon, with the Columbus, New Mexico, raid of Pancho Villa, the U.S. Army was in that market as well, pushing off French and British agents in the US so that it could acquire the horses and mules it required for a much larger Army that was nearly completely horse powered.

Remount shipping point.

Thousands of Americans who had previously had no direct connection with agriculture entered the rush, so lucrative was the grain trade at first, and so little, it seemed, had to actually be done in it. In Kansas new towns sprung up full of such entry level farmers, many of whom didn't actually live on their farms, but in the towns, a practice that is common in some regions, but in this instance reflected an urban centric way of thinking. Soon, these thousands were joined by discharged or soon to be discharged servicemen, many thousands of whom did have practical farming experience and agricultural roots, but who had the surplus cash to start up a farm, or small ranch, for the first time. In Wyoming, hundreds of tiny homesteads, at most 640 acres in size, were filed, which with the favorable weather and market conditions, were actually viable in spite of their tiny size.

The boom couldn't last. It trailed into the 1920s, but by then the prices began to fall. Soon after, the rain began to stop falling. An agricultural depression hit the US far earlier than the general Great Depression did. By the 1930s the situation was desperate, and not only had the economy turned against farmers, but the weather had as well. Finally, in the early 1930s, the government repealed the Homestead acts, and new entries stopped. Many of the teens homestead had already been abandoned by that time, once prosperous hopeful small units, but out place both economically and, as it turned out, climatically.

Related Posts: